From Frescoes to Field Guides: A Journey Through the History of Bird Illustration

Edward Lear's Rainbow Lorikeet illustration for English ornithologist Prideaux John Selby's Natural History of Parrots, 1836.

An Eye for Birds

I have, unashamedly, a deep fascination with birds. Some of my appreciation was developed while studying the behavioral ecology of waterbirds in remote areas of Australia and South Africa. I have been fortunate to spend time in some dramatically beautiful places, environments teeming with cormorants, ducks, swans, pelicans, towered over by gangly storks and punctuated by colorful little gallinules and jacanas darting here and there after their food. Never mind the plentiful crocodiles, these are truly paradises.

But my attraction to birds doesn’t end with field study. I am also a huge fan of the garden variety birds that end up in our feeder, migratory warblers and the American Goldfinch. Brown-headed Nuthatches spreading their wings to ward off bluebirds who pile onto the platform, their scruffy offspring in tow. And then there is that Pileated Woodpecker who stares at the cat through the living room window. I have blogged about the species in our former garden in North Carolina and am eagerly awaiting the spring migration to see what arrives at the Linda Hall Arboretum.

In all this, my scientific background doesn’t afford me any special birding credentials. I am in a truly enormous crowd of bird enthusiasts. In fact, Cornell University’s bird lab reported at the beginning of this year that, according to a nationwide survey, fully a third of American adults, or 96 million people, are active birdwatchers. While this current number is eye-wateringly large, birds have been a source of fascination for a long time, intertwining with many aspects of our lives. Aside from the wonder with which so many of us observe these modern-day dinosaurs, we incorporate them into our diets with great enthusiasm (mostly chickens—34.4 billion worldwide in 2023). We keep them as pets (an estimated 800,000 wild-caught birds are imported annually into the US to be sold as pets). They even accompany us to sleep, their down filling our pillows (270 metric tons of duck down are produced every year, mostly in Europe and Asia). However, these functional statistics belie the enduring allure that has captured people’s imagination and reverence, especially in times long past. |  A Century of Birds from the Himalaya Mountains, by John Gould, 1832 |

Artistic Portrayals of Birds

During the 2023-24 season at the Library, we have shared some of these insights in the exhibition Chained to the Sky: The Science of Birds, Past and Present, developed in partnership with Chicago’s Field Museum. It is a chronicle of our changing relationship with birds from prehistoric times through the modern day, to the future of bird conservation in our own backyards. At every step, the science is accompanied by illustrations. From the ancient cave paintings through the detailed Victorian-era illustrations by Edward Lear, to the contemporary field guides by David Sibley, these artistic portrayals of birds do more than capture their beauty; they provide visual evidence of an evolving relationship. In this article, we celebrate a few of the outstanding people who observed birds and documented those observations to view and ponder.

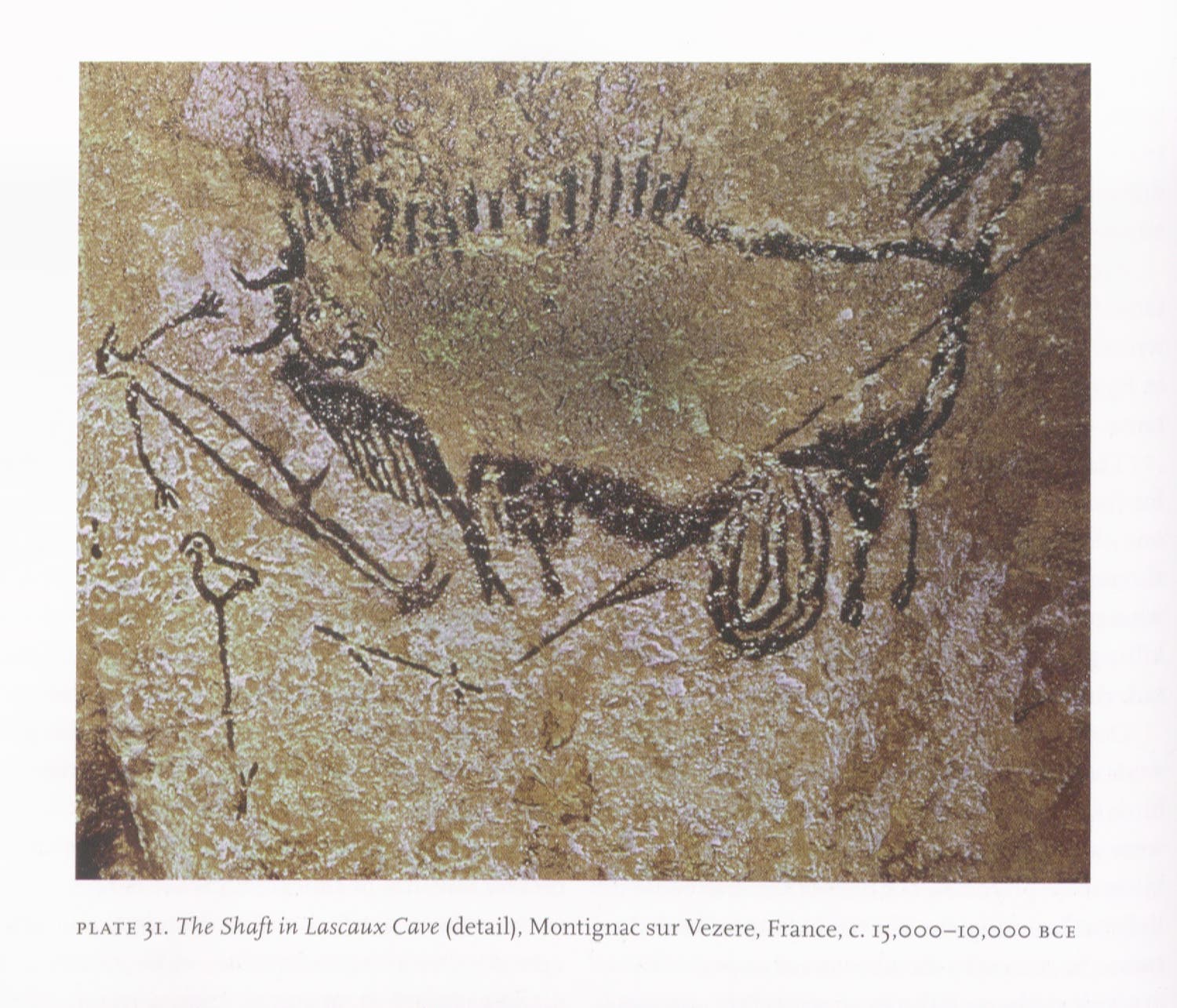

From Lascaux Caves in France, this image of the "Bird Man" is the earliest known depiction of a bird. Darryl Wheye and Donald Kennedy. Humans, Nature, and Birds: Science Art from Cave Walls to Computer Screens, New Haven, 2008.

The Ancient World

Bird illustration as we think of it today was a fairly recent development, although we’ve been capturing images of birds for a very long time. The earliest depiction of a bird by a human is the “Bird Man” of Lascaux, dating back 17,000 years. At first glance, he looks almost comical, arms outstretched with an enormous bird head perched on his shoulders. He is presumed to be a shaman blessing a hunt, as evidenced by a dead bison in front of him. Was this a literal depiction of a man wearing a mask, or a figurative image of somebody drawing power from the sky? On the other side of him, its purpose also unclear, is a pole with a bird on top. We will probably never know the answers; however, these humble yet important beginnings produced a proliferation of beauty and inspiration. From those very early days, it seems, birds have carried a sense of mysticism about them.

The Renaissance

You need to move forward in time to uncover named artists drawing birds for illustrative purposes. In 1512, Albrecht Dürer, a master of the Northern Renaissance, meticulously captured the beauty and detail of the natural world in his artwork, of which his hare is probably the most famous. Among these remarkable studies, the drawing of the wing of a European Roller (Coracias garrulus; pictured on the title page of this article) stands out for its precision and depth, exemplifying Dürer’s skill in rendering the intricate textures and patterns of feathers with almost photographic realism.

Gessner’s publication of Aristotle’s Historia animalium is one of the most important works of Renaissance natural history, linking early modern knowledge with its roots in the deep past. Conrad Gessner, Historiæ animalium, vol. 3, Zürich, 1555. | He, like Leonardo da Vinci, whose manuscripts contain over 500 sketches of birds, bird flight, and machines for human flight, probably drew birds or parts of birds from direct observation, in the same sense we know illustrations today. This was, however, rare for the time. The Renaissance generally is marked by a broader embrace of scientific inquiry and rediscovery of classical knowledge. For instance, the earliest surviving illustrated treatment of Aristotle’s Historia animalium was published in four volumes in Zurich between 1551 and 1558 by the prolific Conrad Gesner, a Swiss naturalist and physician with a fifth volume published posthumously in 1587. A copy of volume three is displayed in Chained to the Sky. |

Conrad Gessner (1516–1565)

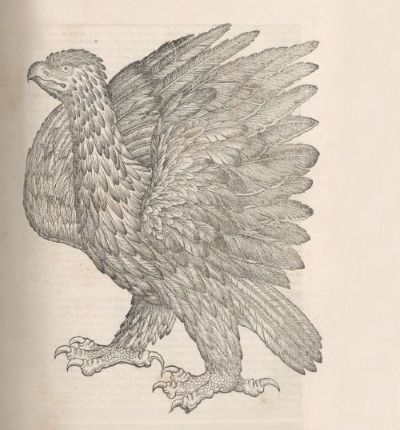

Conrad Gessner, a Swiss naturalist and physician, mentioned earlier for his publication of Aristotle, is often regarded as the progenitor of modern zoology. His seminal work, Historiae animalium, is considered one of the first modern works in zoology and includes extensive descriptions and illustrations of birds. Gessner’s approach combined careful observation with information drawn from classical sources, making his work a comprehensive reference for European natural history in the sixteenth century.

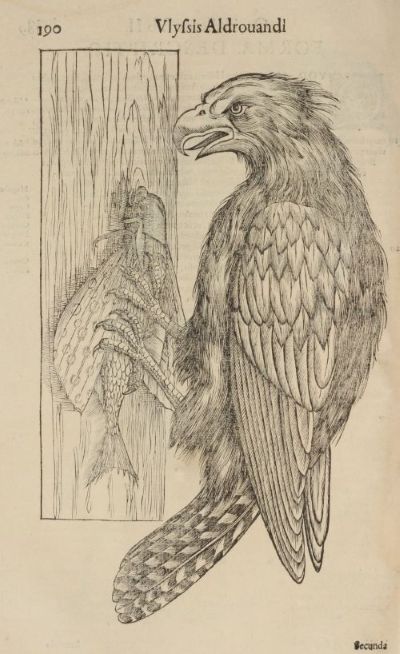

Ulisse Aldrovandi (1522–1605) An Italian naturalist, Aldrovandi is a pivotal figure in the history of natural history, including ornithology. Aldrovandi’s emphasis on mixing empirical observation with traditional historical accounts, along with his extensive collection of natural specimens, greatly influenced the development of natural history generally. His works, particularly Ornithologiae, were among the first to focus exclusively on birds and included rich visuals, which were commissioned from some of the region’s greatest artists, including Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Jacopo Ligozzi, Joris Hoefnagel, and Daniel Fröschl. Much of his extensive collection of specimens is still together and on display at the Palazzo Poggi in Bologna, making it the longest continuously-running natural history collection in the world. The palace is part of the University of Bologna, and the collection is curated and preserved as both a historical and scientific resource. The Palazzo Poggi Museum displays many of Aldrovandi’s original specimens, reflecting his vastly varied interests. In the Chained to the Sky exhibition, we feature this image of an Eagle from Ornithologiae. |  Although the illustrator of this eagle is unnamed, Ulisse Aldrovandi used many of the most important artists of his time to illustrate his seminal works on natural history. Ulisse Aldrovandi, Ornithologae: hoc est de avibus historae libri XII, vol 1. Bologna, 1599. |

The Enlightenment

During the Enlightenment, the study and illustration of birds flourished under the era’s burgeoning zeal for scientific exploration and categorization. This period was characterized by a significant expansion in ornithological knowledge, driven by increased exploration and the collection of specimens from the newly-founded colonies of wealthy European nations. Enlightenment thinkers and artists sought a deeper understanding of the natural world, moving beyond mere observation to a systematic study of birds’ anatomy, behavior, and habitat. This shift is exemplified by works of naturalists like Carl Linnaeus, who developed the binomial nomenclature system, and illustrators like Mark Catesby and George Edwards, who brought the exotic avian species of the New World to European audiences. Birds, in the context of the Enlightenment, were no longer just subjects of artistic representation or religious symbolism; they became integral to scientific discourse, contributing to the broader Enlightenment objectives of knowledge, reason, and the pursuit of understanding the natural order of the world.

Alexander Wilson (1766-1813)

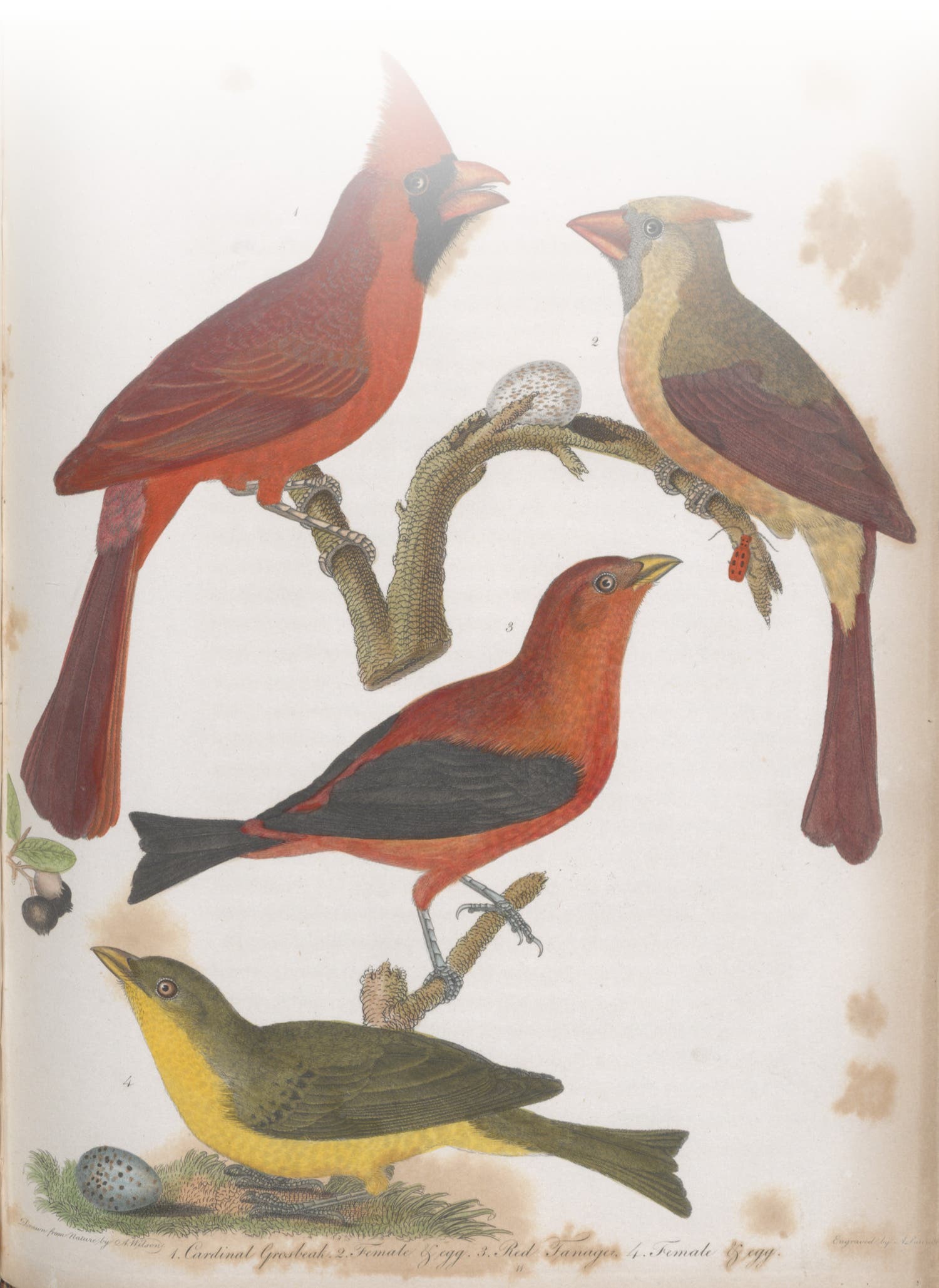

Alexander Wilson was a pioneer in the study and illustration of North American birds. Born in Scotland in 1766 and immigrating to America in 1794, he authored the groundbreaking American Ornithology, published in nine volumes between 1808 and 1814. His extensive travels across America for field observations set new standards for ornithological study. Wilson’s realistic and detailed bird illustrations were influential, laying the groundwork for future ornithologists, including John James Audubon. Despite passing away in 1813 before completing his work, Wilson’s contributions significantly advanced the scientific understanding and appreciation of birds in North America.

Wilson's paintings, like these Cardinals and Tanagers, laid the groundwork for many ornithologists and illustrators that followed. Alexander Wilson, American Ornithology, vol. 1, Philadelphia, 1808.

John James Audubon (1785-1851)

John James Audubon, a Franco-American naturalist and artist, remains one of the most renowned figures in ornithology, primarily for his monumental work The Birds of America, published on double-elephant paper between 1827 and 1838.

This work contained life-sized, hand-colored illustrations of a wide variety of American birds, depicted in their natural habitats. Audubon’s combination of artistic skill and meticulous scientific observation set a new standard in ornithological illustration and profoundly influenced the field of natural history illustration. Unlike his predecessors, whose portrayals often appeared static, Audubon brought an unparalleled vitality to his subjects, portraying them as living, breathing entities within their natural habitats. This approach, in an era before photography, enabled a deeper public appreciation and understanding of birds, fostering a connection with these species. While acknowledging the problematic aspects of Audubon’s history, including his treatment of Indigenous peoples and environmental ethics, his artistic legacy remains significant, bridging the human-avian divide and reshaping our perception of the natural world through art. |  We feature a number of Audobon images in the exhibition, including the Carolina Parakeet, North America's only native parrot, which was sent extinct by humans in 1939. John James Audubon, The Birds of America, vol 4, New York and Philadelphia, 1842. |

Modern Times

From the Victorian era to the present day, the representation and study of birds has seen a remarkable evolution, paralleling the rapid advancements in both science and art. The Victorian era, with its fascination for collecting and classifying the natural world, saw the production of elaborate and detailed bird illustrations in works like John James Audubon’s The Birds of America, which combined artistic splendor with scientific accuracy. This period also witnessed the integration of bird study into the burgeoning field of evolutionary biology. Moving into the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, considerable focus has shifted towards conservation and ecology, reflecting growing concerns about habitat loss and species extinction. Modern bird illustrations, while continuing the tradition of detailed depiction, have increasingly served a practical purpose in field guides and ornithological research, as seen in the works of Roger Tory Peterson and David Sibley.

A Century of Birds from the Himalaya Mountains, by John Gould, 1832 |  A Century of Birds from the Himalaya Mountains, by John Gould, 1832 |

Edward Lear (1812-1888)

Lear was an English artist, illustrator, musician, author, and poet, now most widely known for his literary nonsense in poetry and prose, especially his limericks, a form he popularized.

He was also a highly respected travel illustrator and bird painter, of which the Rainbow Lorikeet Trichoglossus moluccanus in the front of this article (and on display in Chained to the Sky) shows extremely well. Lear’s illustration was part of a series created for Prideaux John Selby’s Natural History of Parrots, which was published as part of William Jardine’s Naturalist’s Library series in 1836. I am particularly fond of Rainbow Lorikeets, having lived for many years in Sydney. They are ubiquitous, raucously invading every suburb and – to me at least – add something distinctive to the character of the city.

David Allen Sibley is a preeminent figure in modern ornithology and bird illustration. His Sibley Guide to Birds, first published in 2000, has become a standard reference in bird identification in North America. Sibley’s work, characterized by its detailed and accurate illustrations of birds in various poses and plumages, combines scientific rigor with artistic finesse. His guides have made the study and appreciation of birds accessible to a wide audience, continuing the tradition of blending art and science in ornithology. Each illustrator, and the many others we did not have space to cover, has contributed uniquely to our understanding and enjoyment of birds, reflecting the changing ways in which these creatures have been viewed and appreciated through time. It is our hope that, by celebrating birds, and the artists who painstakingly captured their anatomy and behavior, we all journey closer to protecting them for future generations.

We warmly welcome you to see Chained to the Sky: The Science of Birds, Past and Future, offering a distinctive look at the world of birds through historical literature, illustrations, and photography. With bird populations facing significant challenges globally, this exhibition aims to educate and inspire visitors to make a difference. So, beyond the celebration of their beauty, we provide practical advice on bird conservation in your own home and garden. Looking forward to seeing you there.

Pictured: David Sibley and Eric Dorfman viewing Chained to the Sky.