Mapping the Heavens

We've had the privilege and joy of working closely with our colleagues across Brush Creek at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art on a collaborative show titled Mapping the Heavens: Art, Astronomy, and Exchange between the Islamic Lands and Europe. This show, opening on December 14, 2024, and on view until January 11, 2026, includes 14 items from the Library's collection, which all illuminate the connections between religions and cultures as seen in the printed books in our collections.

Finch Collins, Assistant Curator of Rare Books, and I spent an afternoon talking about some of those books in support of the video work being done by the Nelson-Atkins for the show – Copernicus, Ulugh Beg, and Alphonse X's tables among them. The final books we talked about were Johannes Hevelius' Prodromus astronomiae cum Catalogo fixarum (1690), & his Firmamentum Sobiescianum (1687). The engraved frontispieces are an integral part of Mapping the Heavens, and in anticipation of the show, I thought people might be interested in a deep dive into these two fantastic engraved images. We'll begin with the frontispiece from the Prodromus, where we see seven figures gathered in an imagined pavilion:

Frontispiece from the Prodromus, where we see seven figures gathered in an imagined pavilion. From left to right, the astronomers are Johannes Hevelius, Wilhelm IV, the Landgrave of Hesse-Cassel, Ulugh Beg, Ptolemy, Tycho Brahe, and Giovanni Riccioli.

The small title at the top of the building tells us what we are seeing: a "synod" of astronomers, who each created a catalog of the fixed stars [Synodus astronomorum, qui prae Aliis fixarum Catalogo operam dederunt], with the Greek muse of astronomy, Urania, in the center. From left to right, the astronomers are Johannes Hevelius, Wilhelm IV, the Landgrave of Hesse-Cassel, Ulugh Beg, Ptolemy, Tycho Brahe, and Giovanni Riccioli. Why these astronomers? As Bill Ashworth pointed out in a Scientist of the Day on Wilhelm IV, each astronomer's catalog of the fixed stars was included in Hevelius' work in the Prodromus. Each astronomer has their name above them in a frame, as well as a motto, one of which bears a little further discussion.

![Tycho Brahe, with his famous nose and mustache, under a motto that he had outside his library at Uraniborg: Non haberi sed esse [Not to seem but to be].](https://preview-assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/42d46246-0872-4de4-93fc-d01f36143513/2.jpeg?w=432&h=1915&auto=format&q=75&fit=crop)

Close up of Tycho Brahe.

You see Tycho Brahe, with his famous nose and mustache, under a motto that he had outside his library at Uraniborg: Non haberi sed esse [Not to seem but to be].

![On the table in front of this imagined scene is the text Quid praestiterimus, et quousque nostrum quilibet sublimem hanc sideralem scientiam, in rerum omnium creatoris gloriam deduxerit, sincera testabitur posteritas [What we have accomplished, and how far each one has brought forth this sublime starry knowledge for the glory of the Creator of all things, the whole of posterity will testify].](https://preview-assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/05e51495-7004-4bd3-a8ee-ca672733e841/3.jpeg?w=1500&h=631&auto=format&q=75&fit=crop)

On the table in front of this imagined scene is the text Quid praestiterimus, et quousque nostrum quilibet sublimem hanc sideralem scientiam, in rerum omnium creatoris gloriam deduxerit, sincera testabitur posteritas [What we have accomplished, and how far each one has brought forth this sublime starry knowledge for the glory of the Creator of all things, the whole of posterity will testify] – which alludes to one of the subtexts of the show. The written and printed record allows astronomers across time, cultures, and languages to be in conversation with one another and to build upon earlier work. Certainly, a gathering of these six people around a table is impossible given the wide range of time they lived in, but they are gathered together in the tables printed in the book. The work of several of these astronomers will also be in the same room at the Nelson-Atkins for the exhibition.

Astronomers gathered together under a barrel-vaulted ceiling decorated appropriately with images of the stars.

Let's look closer at the upper third of the image – the astronomers are gathered together under a barrel-vaulted ceiling decorated appropriately with images of the stars. Above that on the roof of the imagined building are at least nine instruments used to make observations of the sky – Keplerian telescopes, sextants, and quadrants, mimicking those found on the roof of Hevelius' observatory (on a platform above his properties), called "Sternenburg" or star castle.

Let's shift to the frontispiece from the Firmamentum Sobiescianum, which is both similar and different to the one we just looked at in the Prodromus:

Frontispiece from the Firmamentum Sobiescianum

The central subject with his back to us is Hevelius himself. In his left hand is an astronomical sextant, which he and his wife Elisabeth used to measure star positions, and which he proposed as a new constellation. In his right hand is a shield which represents another new constellation, Scutum, called the "Shield of Sobiesci," in honor of the Polish king's (John III Sobiesci) defense of Europe from an invasion by the Ottoman Empire. Hevelius is looking down at an open book, his catalog of the fixed stars, "Catalog[us] Fixarū[m]." The Firmamentum – a star atlas – was intended as a companion to the star catalog, much as John Flamsteed would do in his Atlas Coelestis of 1729. Below and to the left of Hevelius are the six additional constellations he proposed. He appears to be presenting all of these things – from the sextant to the new constellations – to the gathered 11 figures:

From left to right, these figures are Bernhard Walther, Tycho Brahe, Ulugh Beg, Timocharis, Hipparchus, Urania (surrounded by small children, representing the planets), Ptolemy, Albategnius, Wilhelm IV, Johannes Regiomontanus, and Nicolaus Copernicus. In Latin, Hevelius says (as is written on the scroll in front of him) "Quaecunque divina concessit benignitas, haec submisse sisto, atque offero, vestroque sublimi committo judicio" [Whatever Divine Grace has granted, I humbly put forth, offer, and commit these things to your eminent judgment {over his catalog of the fixed stars}], asking the assembled company to judge, and ostensibly approve, his work. Below, and to the right, is a small image of the town of Gdańsk (Danzig), where Hevelius lived and worked.

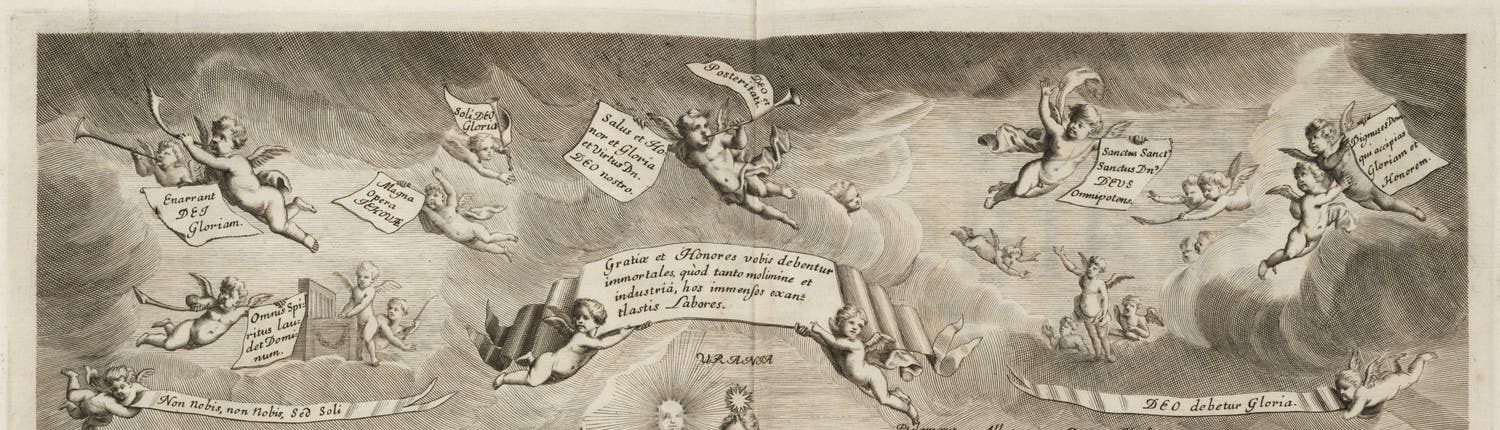

And above all this are a number of putti with religious phrases; the central one bears repeating: "Gratiae et honores vovis debentur immortales, quod tanto molimine et industrua, hos immensos exantlastis labores" [Thanks and honors are due to the immortals, because with so much effort and industriousness, these immense labors were carried out]

As I teased in the beginning, the Hevelius is one of 14 items we'll be loaning to the Nelson-Atkins for this show. If you're in Kansas City in 2025 and want to know what you'll see from the Library there, here's a complete list:

- Muhammad ibn Jabir al-Battani, Mahometis Albatenii De scientia stellarum liber, 1645

- Alfonso X, Alfonij regis castelle̜ illustrissimi Ce̜lestiu[m] motuu tabule, 1483

- Ulugh Beg, Sive Tabulae long ac lat. Stellarum fixarum..., 1665

- Johannes Bayer, Uranometria, 1603

- Andreas Cellarius, Harmonia Macrocosmica, 1661

- Nicolaus Copernicus, De Revolutionibus, 1543

- Nicolaus Copernicus, De Revolutionibus, 1566

- Joseph Solomon Delmedgio, Sefer Elim, 1629

- Johannes Hevelius, Prodromus Astronomiae bound with Firmamentum Sobiescianum, 1690

- Peter of Krakow, Computus astronomicus, 1501

- Ptolemy, Almagestum, 1515

- Johannes Regiomontanus, In laudem operis Calendarij, 1485

- Franz Ritter, Astrolabium, ca. 1640

- Julius Schiller, Coelum Stellatum Christianum, 1627

We're excited to share more about the exhibition and the programs supporting it soon, but in the meantime, I hope Hevelius has piqued your interest in attending!

Special thank-you to Bill Ashworth, Ian Ridpath, Rhiannon Knol, and Finch Collins for their help with this post, and especially the Latin!