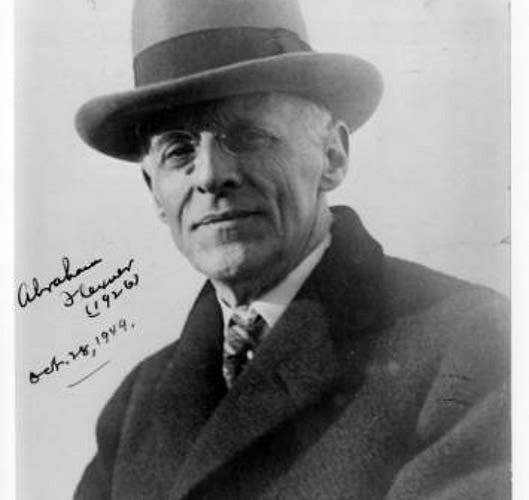

Scientist of the Day - Abraham Flexner

Abraham Flexner, an American educator, was born Nov. 13, 1866. Flexner was so disillusioned by his graduate school experience that he wrote a book, The American College (1908), in which he was highly critical of the lecture system as a means of education, and even more critical of the idea of the research university, where he thought too much energy and funding was devoted to specialized research and not enough to general education. This book came to the attention of the director of the Carnegie Foundation, who asked Flexner to make a study of the country’s medical schools, even though Flexner had never even been inside a medical school.

Flexner accepted the offer, and he spent two years studying over 150 schools that offered medical degrees in the United States. He issued his report in 1910. It had a long-winded title typical of such reports (second image), but it was instantly labelled The Flexner Report, and it is so known right to the present day.

It was a scathing indictment of medical education. The fact was that there was no standard at the time for educating a physician, and no boards to oversee the schools. Many schools for physicians were for-profit institutions that were not even associated with universities. Flexner insisted that a medical school should be science-based and predicated on the germ theory of disease, and that future doctors should not just be taught facts, but should learn how science works and how knowledge is advanced. Physicians need, in other words, a little metaphysics and epistemology with their anatomy. Flexner recommended that most of the country’s medical colleges should close their doors. Amazingly, many of them did just that. The number of medical school in the United States dropped from 155 to about 40 in just a few years. The for-profits were gone. It was now much harder to get a medical degree and be unaware of proper clinical practice, the germ theory of disease, and the Hippocratic tradition. The system of medical education that we have today had emerged, although it should be said that proponents of alternative medicine have never been too pleased with the way the Flexner Report defined what seems to be an overly-rigid medical mainstream.

Flexner was not done. In 1929, he was approached by two wealthy would-be philanthropists, a Jewish woman and her brother from New Jersey, who wanted to found an institution and sought advice. They were inclined to establish some sort of a Jewish hospital or medical school. Flexner convinced them otherwise. What he had in mind was an “institution for useless knowledge”, as he once jokingly called it--a place where the best minds could gather, talk to each other, and come up with new ideas and not worry about whether any of their ideas were practical. The result was the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton University, founded in 1930. Flexner was the first director, and he held the post for ten years. He brought in the likes of Albert Einstein, John von Neumann, Hermann Weyl, Wolfgang Pauli, and Kurt Gödel--five of the best mathematicians in Europe-- and the Institute was off and running. The center of the world of mathematics had now moved to New Jersey.

The first photograph shows Albert Einstein and Flexner (second from left), with two others, at the opening of Fuld Hall at the Institute in 1939. It and the portrait are in the Archives at the Institute for Advance Study. The fourth image shows an aerial view of the Institute campus today. The central Jeffersonian-like building is Fuld Hall, named for the sister-benefactor, and before which Einstein and Flexner were exchanging a private moment of fun in our first image.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.