Scientist of the Day - Académie des Sciences

On Dec. 22, 1666, the French Académie des Sciences met for the first time in King Louis XIV's library at Versailles. The Academy had been organized by Louis's minister, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, as a response to the Royal Society of London, which had been chartered in 1662 by King Charles II. Colbert, however, had in mind a different kind of organization from the English model. The Royal Society, in spite of its charter, pretty much ran itself without any input from the crown. They elected their own members, chose their own subjects to investigate, and did not draw a penny from the royal treasury – indeed, the Royal Society was funded by its own members, who paid dues to keep the institution afloat.

Colbert envisioned an academy that was royal in more than its name. He chose the members (called academicians) himself, and limited their number, originally to 7, and then to 16. The academicians drew a salary from the crown, and in return they were expected to engage in pursuits that would benefit the state, such as surveying France and publishing a reliable map of the kingdom, or building an observatory that might contribute to solving the longitude problem. Moreover, nationality was not an issue. All of the charter members of the Royal Society were British, but the French Academy soon included men of other nationalities. Some of the early Academy members included Jean Roberval, a French mathematician; Christiaan Huygens, a Dutch instrument maker and mathematician; Giovanni Domenico Cassini, an Italian astronomer who was put in charge of the Observatory (and who changed his name to Jean Dominique Cassini); Ole Römer, a Danish astronomer; Claude Perrault, a French physician and anatomist; and Adrien Auzout, a French instrument maker.

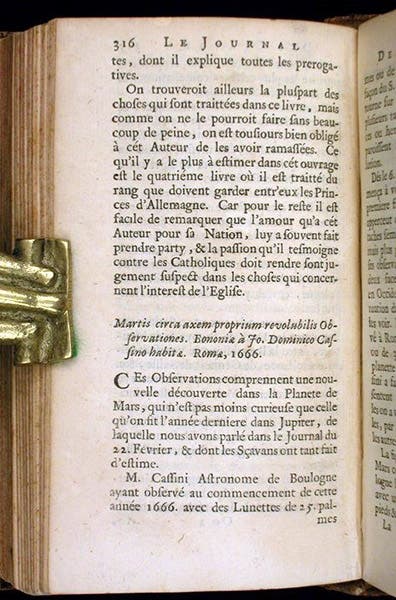

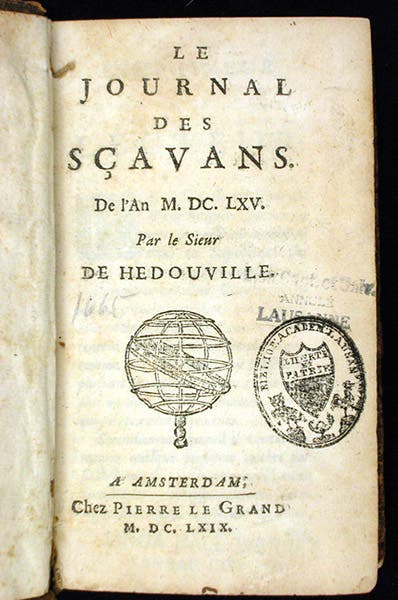

One important difference between the British and French groups is that the Royal Society published a journal. In fact, they invented the scientific journal, the Philosophical Transactions, in 1665. As a result, we have an excellent record of their activities. The French did not follow suit. There already existed in Paris a learned journal called the Journal de sçavans, and so the French Academy published results of some of their work there, but it is a very spotty record (third and fourth images). Not until 1699 did the Academy reorganize, become a Royal Academy in name as well as practice, institute a journal (Histoire et Memoires de l’Académie Royale des Sciences), and publish a retrospective account of their first 33 years of activity.

There are several illustrations that depict early meetings of the Academy. One was an engraving by Sébastien Le Clerc that was first published in 1671 and subsequently appeared in several Academy publications. We have two impressions in two different books in the History of Science Collection. The fifth image below shows the entire engraving; the sixth image is a detail. Louis XIV is at left center (wearing the hat) and Colbert is at right center. One of the bronzes that used to grace the exterior of the Linda Hall Library was based on this engraving. When the Library later added a stack building, the bronze plaque was displaced, refinished, and moved into the auditorium, where you can see it today. We showed it as the fifth image in our recent post on Bruno Bearzi, the foundryman who made them.

One other early group portrait of the Académie des Sciences is a painting by Henry Testelin, supposedly done in 1667 but evidently completed at least 8 years later, which shows the academicians being presented to Louis XIV at Versailles (first and second images). Neither Le Clerc’s engraving nor Testelin’s oil painting captured a real historical meeting; there is no indication that Louis XIV took any interest whatsoever in his Academy until the early 1680s, and he certainly did not attend any of their meetings.

Presumably the room that held Louis XIV's library is still there at Versailles, but if it is the same room that Louis XVI used for his library, there is no point in showing it, since Louis XVI had it completely redone in the new Louis XVI style. Perhaps there is some 17th-century painting, unknown to me, that shows the library as Cassini and Huygens would have seen it.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.