Scientist of the Day - Agostino Bassi

Agostino Bassi, an Italian entomologist and microbiologist, was born in Lodi on Sep. 25, 1773. From an early age he was passionate about biology, especially insects, but he earned his living elsewise, managing the family property, and never had an academic position. He became interested in muscardine, or mal de segna, a disease of silkworms, after it first appeared in Italy when he was about 35 years old. Silkworms would die, and on their dead bodies, a white powder would appear, and nearby silkworms would then die and produce the white powder as well; very quickly, an entire silkworm farm would be lost

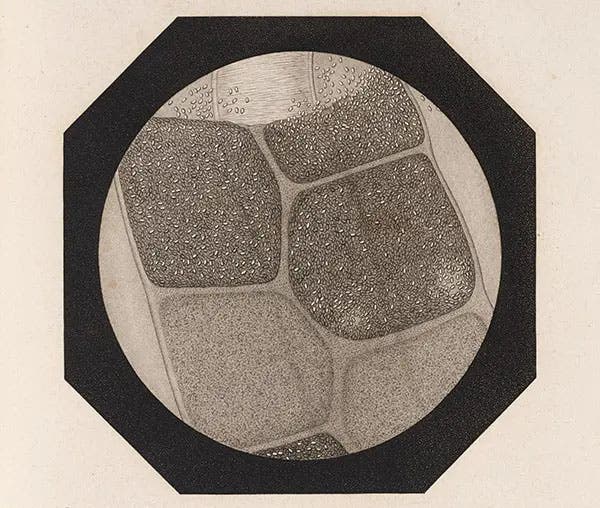

Bassi investigated muscardine for nearly 30 years. He hypothesized that the powder was produced by some living organism that killed the silkworms and created the powder. By the late 1820s, when suitable compound microscopes were available, he acquired one by Giovanni Battista Amici and studied the dead silkworms, and he thought he could detect the presence of a fungus, which would mean that the white powder consisted of spores, which spread the fungus. The actual microscope he used is supposed to be in a museum in Lodi, but I could not find an image, so we show a similar Amici microscope in the Museo Galileo in Florence (third image)

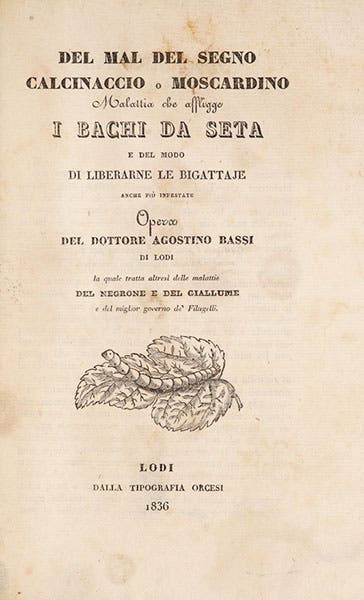

IN 1835-36, Bassi wrote and published a two-part treatise, Del mal del segno, calcinaccio o moscardino: malattia che affligge i bachi da seta (On the Evil Sign, Calcinaccio or Muscardine: A Disease that Afflicts Silkworms). Here, for the first time, a disease was attributed to a microorganism. In addition, Bassi gave detailed instructions on how to stop an outbreak of muscardine. The powder or spores were the key – you had to keep them from spreading, by moving the caterpillars further apart, by the workers making sure that their hands and clothes were clean and not carrying spores, by destroying infected caterpillars away from the rest.

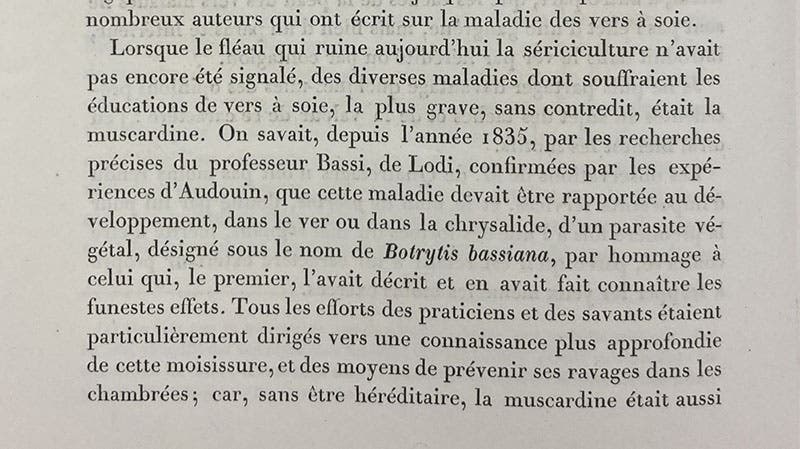

Unfortunately, hardly anyone outside Italy (and not many outside Lodi) read Bassi's little treatise, and the onset of muscardine in the French silkworm industry did not begin until 13 years after Bassi had published his pamphlet (which, ironically, had been translated into French). The French silkworm industry was totally wiped out by 1859. Louis Pasteur would revisit the problem in the mid-1860s and rediscover the cause of the silkworm plague, and publish his own book, Études sur la maladie des vers a soie (1870), this time with beautiful photomicrographs of the tell-tale spores (second image). Pasteur knew about Bassi's work and gave him credit in his own book (fifth image), but no one paid any attention, and Pasteur has always been called the father of the germ theory of disease. But Bassi was really the first to trace a disease to a microorganism, and to suggest that other diseases might have similar origins. The fungus that causes muscardine was named Botrytis bassiana (now Beauveria bassiana), in his honor. Bassi died in 1856, so he did not live to see this acknowledgement.

We do not have Bassi's book in our collections (we show the title page from the online copy at Biodiversity Heritage Library, fourth image), but we do have Pasteur's, with its graphic images of diseased silkworms that I choose not to include here, with the one inoffensive exception (Bassi's book had no illustrations at all). It would be nice to acquire Bassi's treatise some day.

Bassi has not been so much unknown as he has been unsung, at least in English- and French-speaking countries. But in Italy, he is justly acknowledged as a pioneer in biology, and especially so in Lodi, where his tomb is prominently displayed in the Church of St. Francis (seventh image). The Italian government also issued a postage stamp in his honor in 1953 (sixth image).

Portraits of Bassi have never been very glamorous – mostly variants of the one we show above. So I thought it might not be inappropriate to include here – for the first time in our series – an AI-generated portrait of Bassi, produced by the AI software Midjourney for an article in the Wall Street Journal just last year, in 2023. I do not know if the impetus came from the author, Virginia Postrel, or the Journal, but either way, I rather like it. It breathes some welcome life into the microbiologist from Lodi (eighth image, below).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.