Scientist of the Day - Agostino Scilla

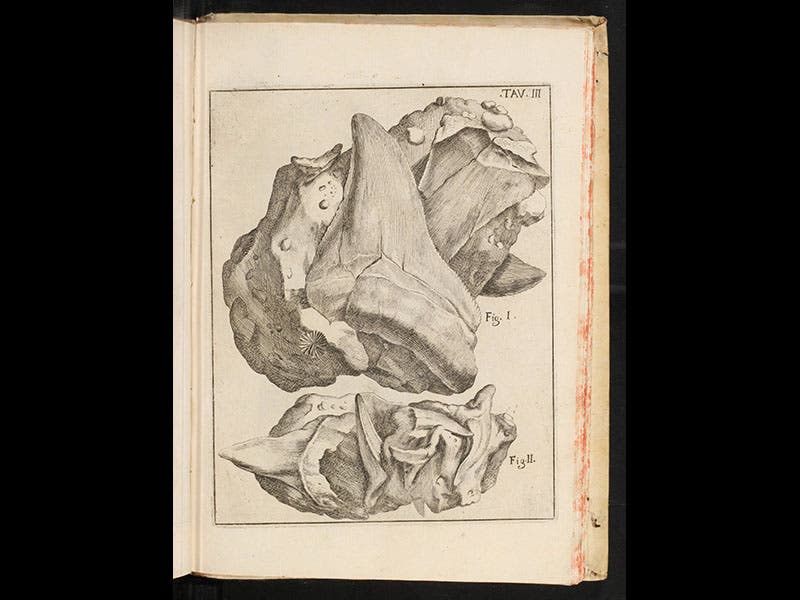

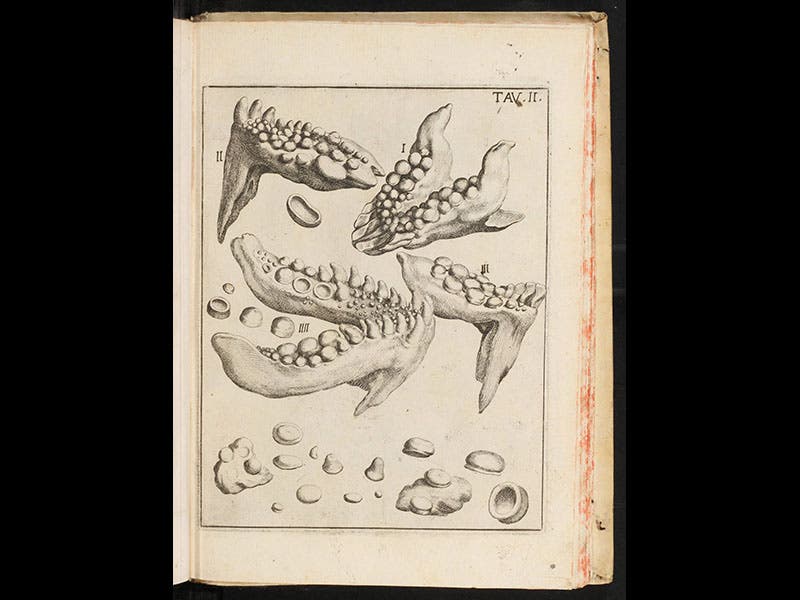

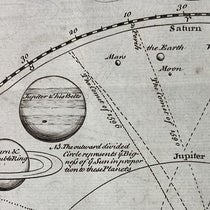

Agostino Scilla, a Sicilian painter and naturalist, was born Aug. 10, 1629. Scilla was an excellent artist, studying under Andrea Sacchi in Rome before returning to his native Messina. But Scilla grew interested in fossils—figured stones as they were called at the time—and especially in the "tonguestones of Malta", those curious specimens from the Mediterranean island that resembled large teeth or, to some, serpents' tongues (second image). In 1670, Scilla published a treatise arguing that fossils are the remains of formerly living organisms, and not "jokes of nature" that grew in the rocks where they were found. In particular, he maintained that tongue-stones are fossilized sharks’ teeth. He was not the first to make this argument—Nicholas Steno had done so in 1667, and so had Robert Hooke in 1668 (although his work was unpublished). What distinguished Scilla was the priority he gave to sense evidence in recognizing the true origin of fossils, and to an important spin-off of sense evidence—pictures. There are 30 engravings in his book, beautifully drawn by Scilla himself, which he uses as an important part of his argument (Steno had included only two engravings in his publication, and both had been borrowed from an unpublished manuscript that had been lying around Rome for almost a century).

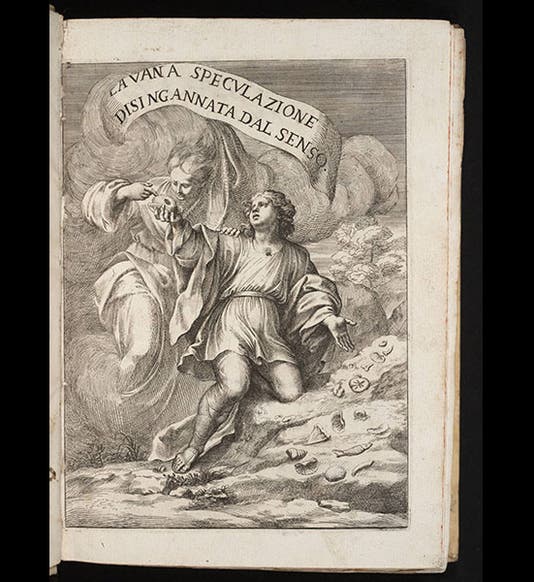

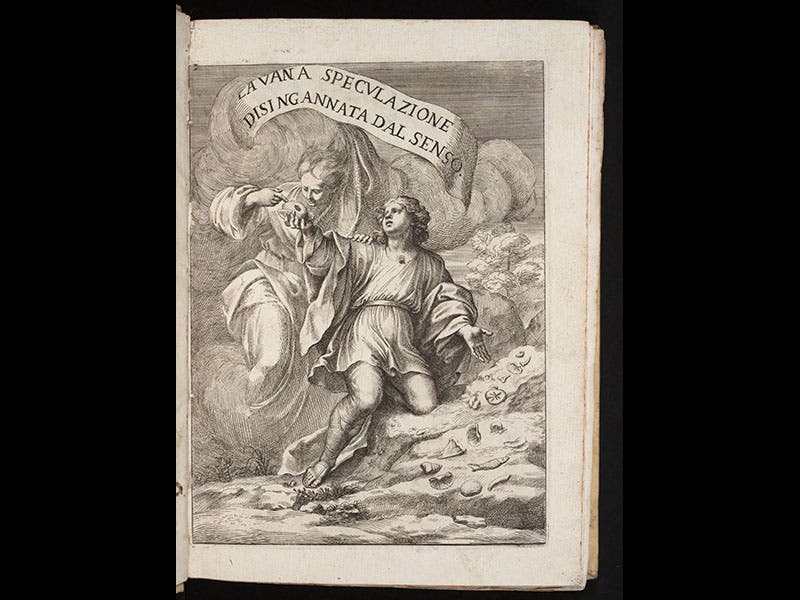

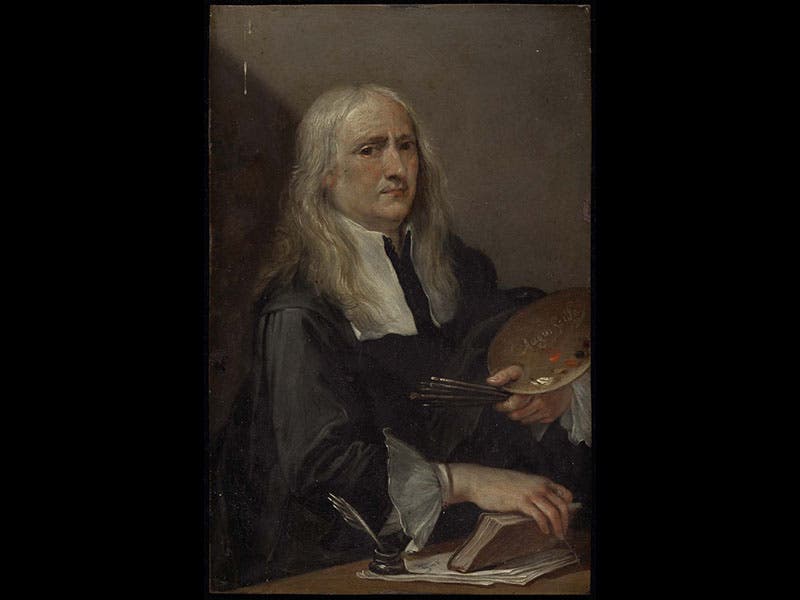

Even the title of Scilla's book was chosen to make a point about evidence; he called his treatise La vana speculazione disingannata dal senso (Vain Speculation Undeceived by Sense). On the allegorical frontispiece of the book (first image), which Scilla also designed, a personification of Sense is presenting a fossil shark’s tooth and sea urchin to a wispy academic philosopher, seemingly asking: “Why do you believe your books, and not your eyes?” We have several of editions of Scilla's treatise, including the first of 1670, in the History of Science Collection.

The original drawings that Scilla did for his book survive, as well as many of his actual specimens—they are in the Woodwardian Museum at Cambridge in England. A photograph shows two of his fossils (third image), next to the sketch that Scilla made of them. The engraved plate that was produced from the drawing is also shown above (fourth image).

The Museum of Fine Arts in Boston has a portrait by Scilla which they claim depicts his teacher, Andrea Sacchi (fifth image). However, the leading authority on Scilla, Paula Findlen at Stanford, argues convincingly that this is surely a self-portrait of Scilla, as it closely resembles another self-portrait in Messina.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.