Scientist of the Day - Albert of Saxony

Albert of Saxony, a German philosopher and teacher, died July 8, 1390, at the age of about 74; we do not know exactly when he was born. We do not often have the opportunity to showcase a medieval scientist in this forum, since most of them lack known birthdays and/or death days, and thus they don't often show up in searches for anniversaries. Albert is a welcome exception. He came from Helmstedt in Saxony, as his name indicates, and he studied in Prague and then at the University of Paris, where he was the student of Jean Buridan, a medieval physicist with no known associated dates, but who certainly deserves a post someday, and a fellow pupil of Nicole Oresme, who does have a known death date and has been the subject of an essay here.

Albert taught at the University of Paris for 11 years, before becoming bishop of Halberstadt in Saxony. Before assuming that post, he was instrumental in founding the University of Vienna in 1365, where he was the first rector.

Albert is best known for contributing to the theory of impetus advanced by his mentor Buridan. Impetus was an old solution to a problem in Aristotelian physics. According to Aristotle, violent motion (motion contrary to nature) requires a force; remove the force, and motion ceases. This worked fine for Sisyphus, rolling his rock up the hill, but not so well for projectiles, which continued to fly once released from their bow or catapult. To account for projectiles, Aristotle surmised that the air displaced by the front of the projectile moved to the rear and helped push the projectile ahead. This was obviously unsatisfactory, and various alternatives were proposed, culminating in the impetus theory of Jean Buridan, which Albert adopted and improved.

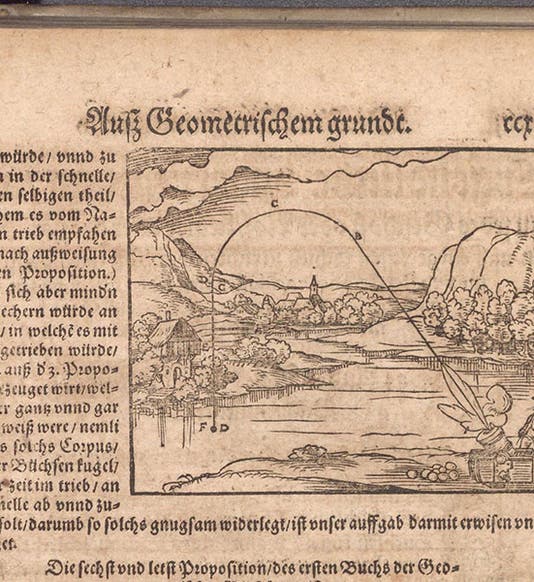

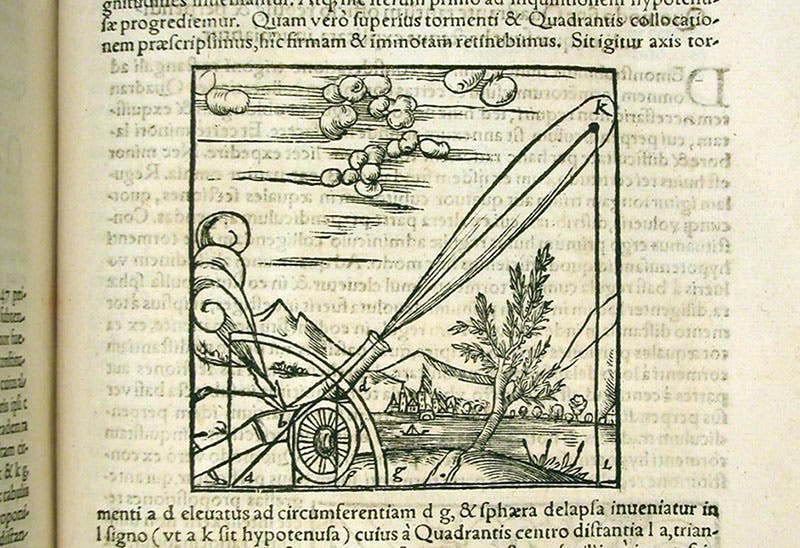

Impetus is a force transferred to a projectile by the original moving force, a kind of internal force of external origin, which keeps the projectile moving. If motion requires a force, impetus is the internal force that provides continuing motion. When impetus bleeds away, the projectile slows and stops, and gravity takes over. Since forces cannot mix in Aristotle’s physics, the projectile moves in a straight line until gravity replaces it. Albert suggested that there is a short transition period, a curved arc, during which impetus is replaced by gravity. It appears that Albert’s curved transition is depicted in a woodcut diagram of projectile motion in Walther Ryff’s Bawkunst, oder, Architectur aller fürnem̄sten (1582), that we have in our collection (first image). It is NOT included in a similar diagram in Daniel Santbech’s Problematum astronomicorum et geometricorum (1561), where all the projectile trajectories lack the curved transition path (second image).

If impetus sounds like inertia, that is not surprising, since it has a similar intent, but is actually quite a different concept. Impetus is a force you put into an object; inertia is an inherent property of an object, dependent on its mass. Getting from impetus to inertia required the genius of Galileo, and was one of the hallmark features of the birth of modern physics in the 17th century.

Albert may not have been much of an original thinker – he was eclipsed by both Buridan and Oresme in that department – but he was a clear writer, and his commentaries on Aristotle’s books on cosmology and physics circulated widely, including down into Italy, whereas the immediate influence of Buridan and Oresme was limited mostly to Paris and Oxford. When Galileo learned about impetus, he probably acquired his knowledge from either a book by Albert, or more likely, a book by someone in Italy who read Albert.

Albert’s commentaries were printed, when printing was established, but we have no works by Albert in our library. However, we are happy to have the two books with sections on ballistics from which we drew our two diagrams.

I do not know of a portrait of Albert, although the MacTutor History of Mathematics website shows one, and that is a usually reliable website. But no source is given. I suspect that in one of the many Albert manuscripts in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, there is an illumination that depicts Albert. The MacTutor image looks like it might have come from such a source. We just need to know what it is.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.