Scientist of the Day - Aldus Manutius

Aldus Manutius, an Italian humanist, printer, and typographic innovator, died Feb. 6, 1515, at the age of about 65. Also referred to as Aldo Manuzio, Aldus had a good thing going as resident tutor to the two nephew princes of Giovanni Pico della Mirandola, when he suddenly, at about age 40, decided to move to Venice and establish himself as a printer. He was a great admirer of the Greek classics and wanted to print the works of Plato, Aristotle, Herodotus, and Sophocles in the original Greek.

In 1490, no one was printing texts in Greek. Printing in Latin was a cinch; you just needed a set of type with 23 upper- and 23 lower-case letters, 10 numbers, and a few punctuation marks, and the typesetter was ready to go. Greek was much more difficult, since it required the insertion of a variety of diacritical signs and breathing marks, requiring enormous and complicated type cases.

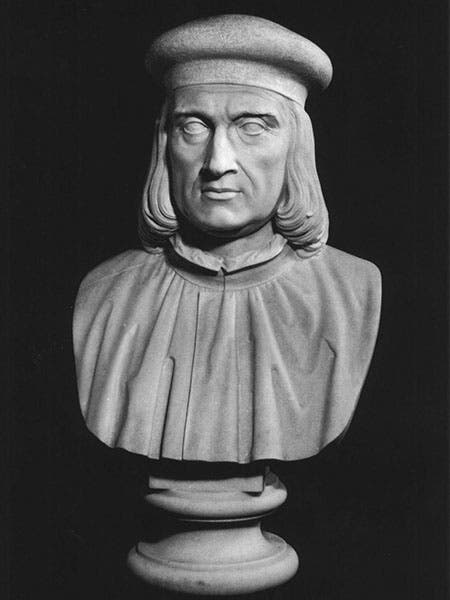

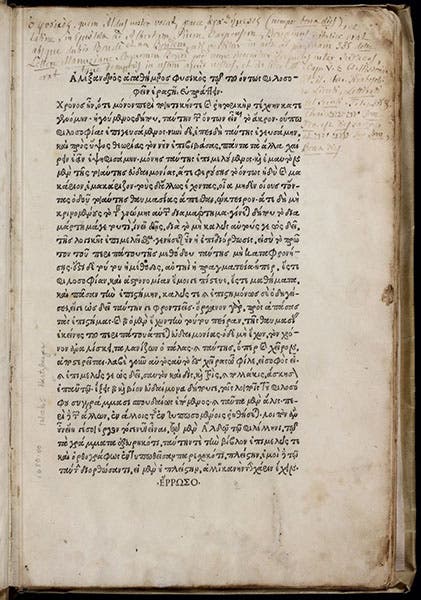

Aldus spent five years devising a simplified typecase, with separate incidental marks that interlocked with the letters in an ingenious fashion, greatly reducing the number of individual pieces of type required. In 1495, he published the first volume of the Opera of Aristotle in Greek, a project that would extend over four years and 5 folio volumes. We have the set in our history of science collection, and show you the first page of the first volume (third image)

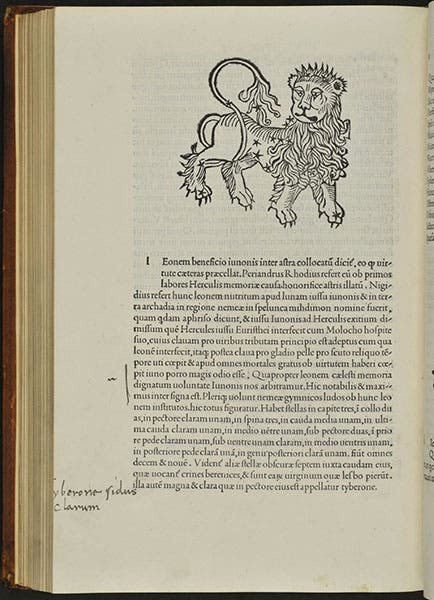

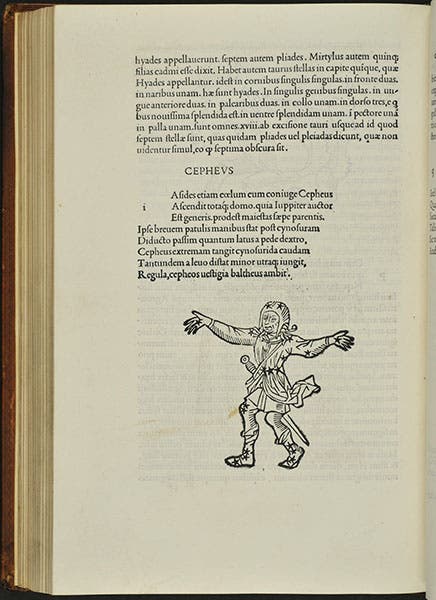

Aldus did not print many scientific books – his focus was rather on Greek literature, and then Latin literature, such as Virgil's Aeneid. But in 1499, he did publish a collection of ancient texts on astrology and the constellations, including poets such as Firmicus Maternus, Manilius, Proclus, and Aratus, a volume that is usually called Matheseos Liber. The section including Aratus's Phaenomenon is noted by the inclusion of woodcut constellation figures. Granted, these are mostly copies of the woodcuts in the edition of Hyginus, published 17 years earlier by Erhard Ratdolt in Venice. But Aldus's wedding of typeface and woodblock is beautiful, for Aldus never printed anything that was not elegant and harmonious (fourth and fifth images).

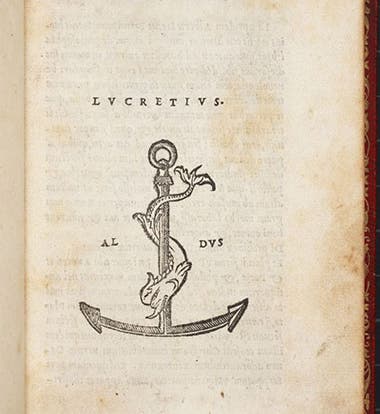

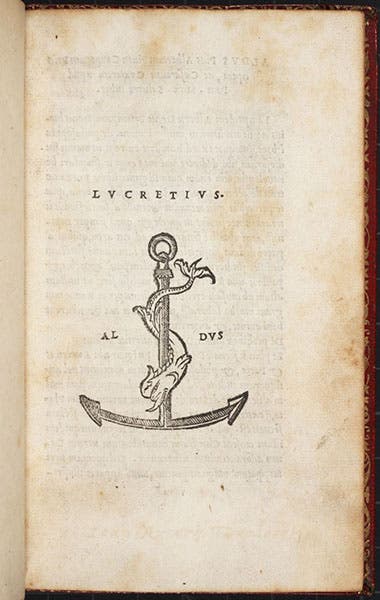

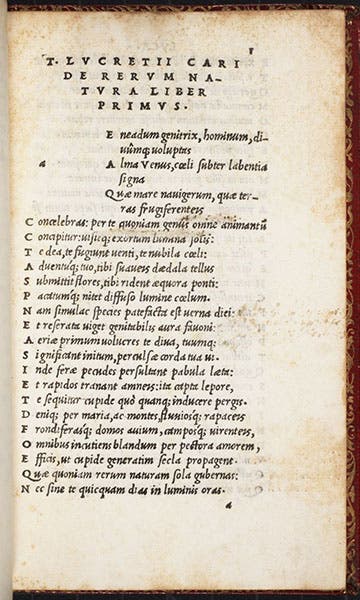

Aldus was innovative in many other ways. He invented the octavo format, where the printed sheet is folded three times to produce 8 leaves and 16 pages, resulting in a smaller book than the folio and quarto formats that he used for his Aristotle and Matheseos Liber. Octavos used less paper and were cheaper to print, and thus cheaper to buy, and helped make libraries both affordable and portable. They also required a cozier typeface, which Aldus and a colleague invented, now called italic, with which Aldus printed most of his octavos. He only did one scientific book like this, the last book he printed before his death, the De rerum natura of Lucretius, our primary source on Greek atomism (sixth image). Our copy also displays the famous printer’s mark of the Aldine Press, the anchor and dolphin (first image), which was suggested to Aldus by Desiderius Erasmus when he was living with Aldus in 1508 while Aldus printed an enlarged edition of his Adages. With its motto, festina lente – make haste slowly – it is the perfect emblem for an innovative but deliberate printer like Aldus Manutius.

Four years ago, Jason Dean, our curator of Special Collections at the time, as part of a video series called After Hours, engaged in an extended conversation about Aldus with G. Scott Clemons, a noted collector and authority on the Aldine Press. The discussion is excellent and insightful and may be seen on Vimeo at this link.

Dust jacket of Mr. Penumbra's 24-Hour Bookstore, by Robin Sloan (2012), in which Aldus Manutius and his legacy plays a prominent role in a novel about the place of the printed book in a digital age (author’s copy)

Also, I thought I would mention a novel that I read a dozen years ago, by Robin Sloan, called Mr. Penumbra's 24-Hour Bookstore, in which a 500-year-old secret society that started with Aldus plays a central role. It is one of many novels that wrestles with the problem: what will become of the printed book in the age of Google?, but does so in a light and clever way that I enjoyed.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.