Scientist of the Day - Alessandro Volta

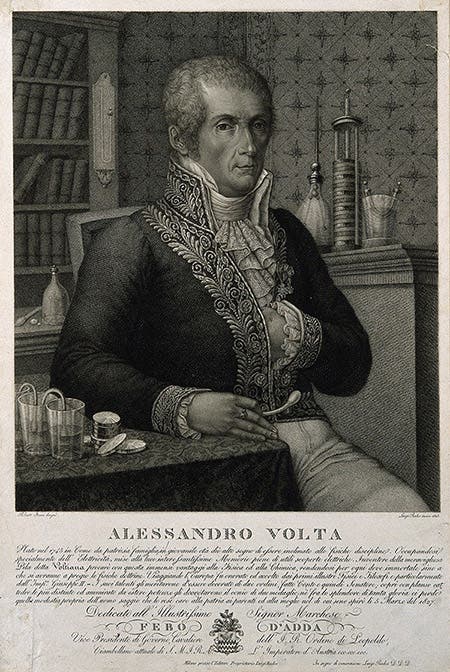

Alessandro Volta, an Italian physicist, was born Feb. 18, 1745, in Como, Italy. Volta was a professor at Pavia when Luigi Galvani did his famous experiments on frogs in 1791. Galvani had found that when he impaled the torsos of recently killed frogs on brass hooks and allowed the legs to touch an iron grate, the legs kicked and convulsed. Galvani concluded that he had discovered evidence of a new kind of electricity, animal electricity. Volta observed some of Galvani's experiments and read his paper, but he was not convinced that a new kind of electricity was being manifested. Volta thought that perhaps the frog tissue was not generating electricity, but reacting to it, and that the key element of the experiments was that Galvani used two kinds of metal in conjunction with moist tissue. So Volta did his own experiments and found that if one separated two plates made of different metals, such as silver and zinc, or copper and zinc, with paper or rags moistened with salt water, then the two plates generated a small electrical current. In order to multiply the current, Volta made round discs of metal and stacked them up in a pile, each pair of discs separated by moist paper, and he found that he could create a sizable potential difference (we would say voltage) between the top and bottom of the pile. This "Voltaic Pile" was the world's first battery.

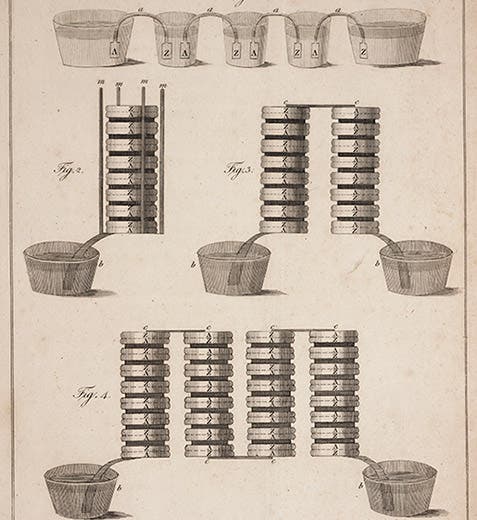

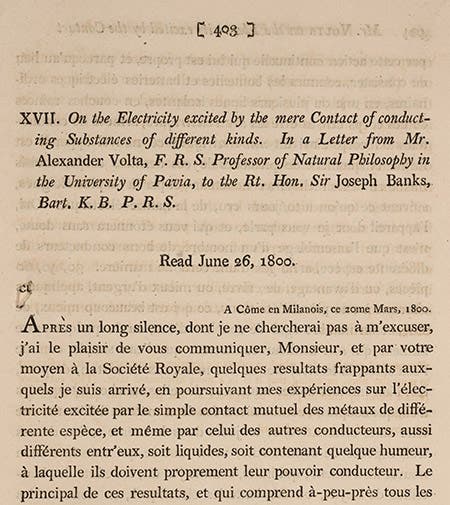

When Napoleon invaded Italy, Galvani refused to recognize the French upstart, and as a result, lost his job, and died soon thereafter. Volta was more politic, if less admirable; he embraced the new foreign regime, and Napoleon became one of Volta's greatest fans, especially after Volta gave him a personal demonstration of his pile. In order to announce his invention publicly, Volta went outside of Italy and sent a paper to the Royal Society of London (in French) with an introductory letter to Sir Joseph Banks (third image). The paper was read to the Society in the spring of 1800 and published almost immediately in the Society's Transactions, along with an illustration detailing the construction of a Voltaic pile. It is the first printed illustration ever of a battery (first image).

The beauty of the battery is that anybody can make one, once he has read Volta's paper or looked at the engraving. Before Volta, the only good source of electricity was the static electrical generator, which produced mainly sparks. The battery allows one to generate a continuous current, quickly and cheaply. Humphry Davy in London learned how to use a battery to electrically break down solutions and separate them into their constituent elements, discovering potassium, sodium, calcium, chlorine, and a host of other elements in short order. The battery was the invention that launched the age of electricity that played such an important role in 19th-century science and technology.

There are a few original Voltaic piles that still survive. There is one in the Royal Institution in London, given by Volta himself to Michael Faraday, and another in the Musée des arts et métiers in Paris (fourth image).

But if you want to see a Voltaic pile in just the right ambiance, travel to Como in northern Italy. Como was Volta’s home town, and they are very proud of their native son. They have erected a statue of Volta in the city square (fifth image), and have also built a museum, the Tempio Voltiano (sixth image) that has several more original Voltaic piles on display.

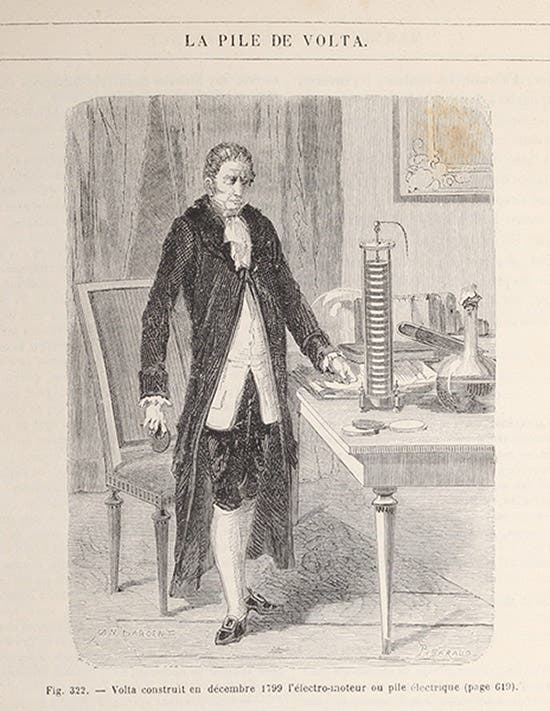

The 19th-century illustrator of the history of science and invention, Louis Figuier, was apparently quite an admirer of Volta, and he included in his Les Merveilles de la science no less than three wood engravings of Volta: one standing with his pile (seventh image); another showing his letter being read to the Royal Society of London; and a third depicting Volta demonstrating his pile for Napoleon. We show you one of those here and link to the other two.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.