Scientist of the Day - Alexander Friedmann

Alexander Alexandrovich Friedmann, a Russian mathematician and physicist, was born in St. Petersburg in 1888 and died in Leningrad on Sep. 16, 1925, in what was in fact the same city. In between, it was called Petrograd, and while Friedmann was living in Petrograd, he wrote and published two papers on general relativity that are going to be the subject of our post today.

Albert Einstein had published his first paper on general relativity in 1915, which essentially offered a new theory of gravitation, proposing that gravity is the result of the curvature of space-time. He made several predictions in the paper, such as that starlight would be bent by the gravitational mass of the sun, and this curvature should be visible in a total solar eclipse. When this was confirmed in 1919 by multiple eclipse expeditions (see for example our post on Arthur Eddington and Frank Dyson), general relativity and space-time was suddenly front page news, and Einstein a world celebrity. We mention this because it was the limelight directed at Einstein after 1920 that attracted the attention of Friedmann in Petrograd, who was working on meteorology at the time, sending up weather balloons, and who decided to read Einstein’s papers with some deliberation.

But it wasn't the first paper that got Friedmann really interested - it was a second paper Einstein published in 1917, which examined the implications of general relativity for cosmology. In fact, this paper marks the birth of modern cosmology. Einstein tried to find solutions of his field equations of 1915 that would tell us what is really going on in the universe. But he ran into a problem, in that the initial cosmological models tended not to be static – they expanded or contracted. Since everyone pretty much agreed in 1917 that the universe is static, and as there was no evidence yet that it might be expanding, Einstein introduced a factor that he called his "cosmological constant," which kept the universe from expanding. This constant first appeared in the 1917 paper.

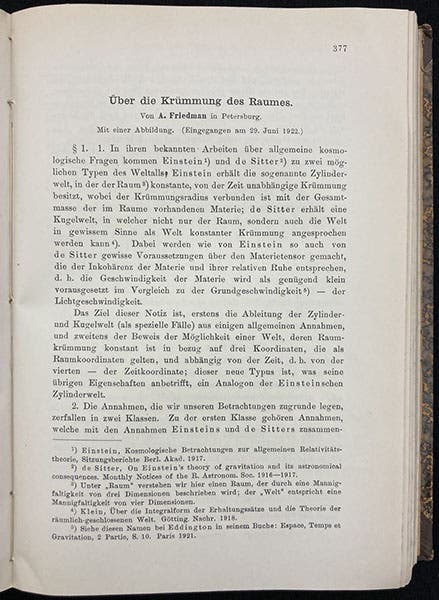

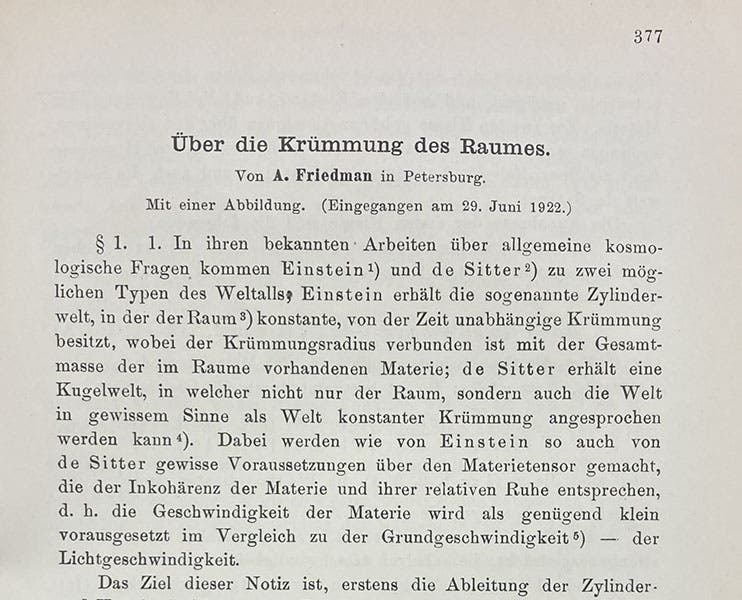

Friedmann was also aware of the work of Willem de Sitter, who derived several cosmological models that Einstein had not considered, including one that was empty of matter, but which had the odd feature that if you introduced a particle, it would move outwards, or “expand.” You can read more about this in our post on de Sitter. And you can see de Sitter’s name mentioned in the first paragraph of Friedmann’s first paper (third image), which we will discuss right now.

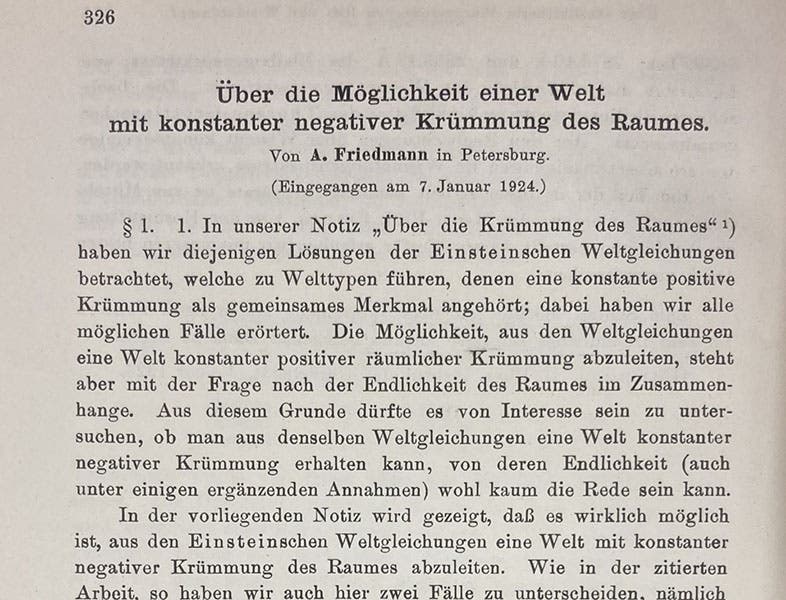

Friedmann was able to come up with a set of solutions for Einstein’s field equations that was perfectly consistent but predicted a universe that expanded over time. Depending on the density of matter in the universe, the expansion might stop at some point and start to contract, or it might just expand forever. Friedmann published his paper, titled “On the curvature of space,” in a new journal, Zeitschrift für Physik, in 1922 (a journal that apparently was much needed, as it had gone through 10 volumes already since its founding in 1920), and he sent a copy to Einstein, and when Einstein did not respond, he sent a friend. Einstein thought he found a mistake in Friedmann's work, and sent off a note to the editor, but Friedmann, in a second letter, showed that in fact the mistake was Einstein's, and Einstein was forced to agree. Friedmann expanded on his original paper in a second one, published in the same journal in 1924 (fourth image).

Well, as you probably know, the universe is expanding, which makes Friemann the father of the expanding universe. Three years later, in 1927, a Belgian astronomer-priest, Georges Lemaître, completely unaware of Friedmann’s two papers, published his own paper arguing for an expanding universe, motivated not so much by theory as by observations from the real world that many galaxies are moving away from us. Lemaître learned about Friedmann’s work from Einstein himself, at the 1927 Solvay conference in Brussels. And two years after that, Edwin Hubble revealed that there is a relationship between the recession speed of galaxies and their distance from us, which suggested (at least to others) an expanding universe. Hubble was also not aware of Friedmann, although he couldn’t have read him if he had been; relativistic cosmology was not his metier.

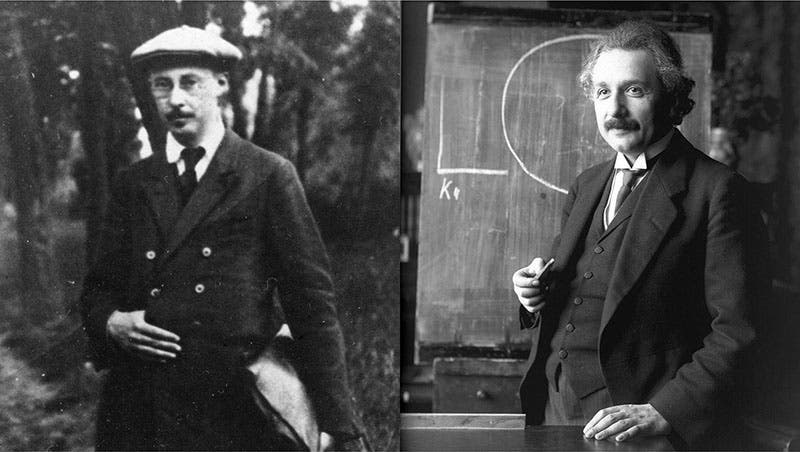

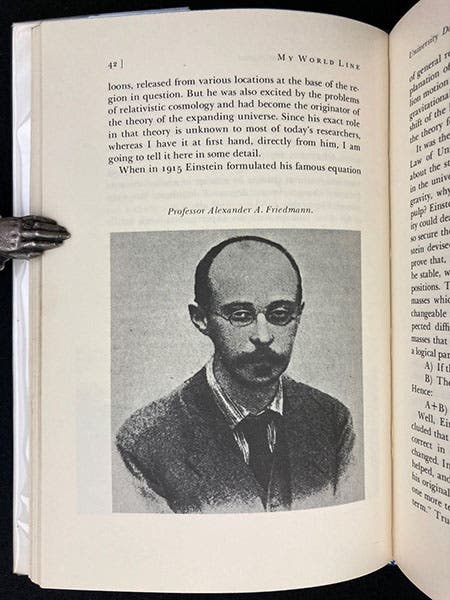

Portrait of Alexander Friedmann, source and date not given, in George Gamow’s My World Line: An Informal Autobiography, 1970 (author’s copy)

To point to the end of the story without going there, Lemaître in 1931 suggested that the universe might be expanding from the explosion of a “primeval atom,” and 17 years after that, in 1948, George Gamow, Ralph Alpher, and Robert Hermann proposed the “Big Bang” hypothesis of the origin of the expanding universe. Gamow, perhaps not coincidentally, studied with Friedman in Petrograd/Leningrad in the early 1920s, and his unfinished autobiography, My World Line (1970), is one of the few sources that sheds any light on Friedmann the person. We have published a post on Gamow.

And what was Friedmann doing while all these astronomers and cosmologists were rediscovering his work? Sadly, he was dead, having passed away on this day in 1925. According to Gamow, Friedmann went up in a weather balloon, caught a chill, and died. According to most other sources, Friedmann died of typhoid fever. Either way, he was gone at the age of 37, and unable to witness the success of his equations for an expanding universe and his growing prominence in the history of cosmology.

Friedmann’s work allowed Einstein to retract his cosmological constant. It is said that he later called its introduction the “biggest blunder” of his career. And how do we know this? Gamow told us so, in his autobiography, in the section on Friedmann. So far as I know, there is no other evidence that Einstein actually felt this way. After all, he introduced it for a good reason. When Friedmann provided a better reason why we don’t need it, he took it out. This was a tactical error, not a strategic blunder. Einstein is forgiven. Gamow is not. Although Gamow did provide us with a portrait of Friedmann in My World Line (without, characteristically, giving the source) (fifth image). Since there are few other portraits of Friedmann, it is nice to have this one.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.