Scientist of the Day - Alois Senefelder

Alois Senefelder, a German actor and playwright, was born Nov. 6, 1771. Sometime before 1796, needing to print a play he had written but unable to afford publication costs, Senefelder experimented with printing from a polished stone that he etched himself. The process worked, and soon he turned this experiment into a novel technique called lithography, which does not require any etching at all; an artist could draw directly on the stone, which then, with proper treatment, could be used to print the image.

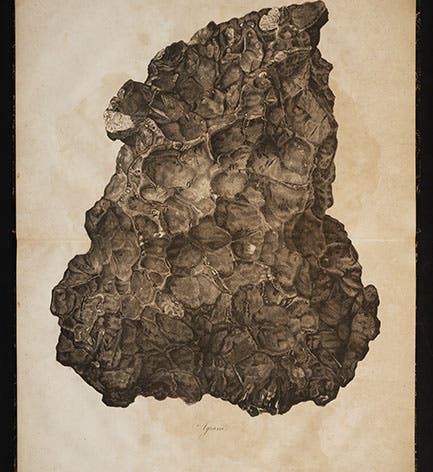

Lithography spread quickly, and by the 1830s, it was in wide-spread use for scientific illustration. We show here some of the earliest lithographs we have in our collections. We featured Karl von Schreibers last August as a Scientist of the Day; his lithographic prints of meteorites (1820; first image) were much more realistic than any earlier such illustrations, primarily because nothing prints a stone better than a stone.

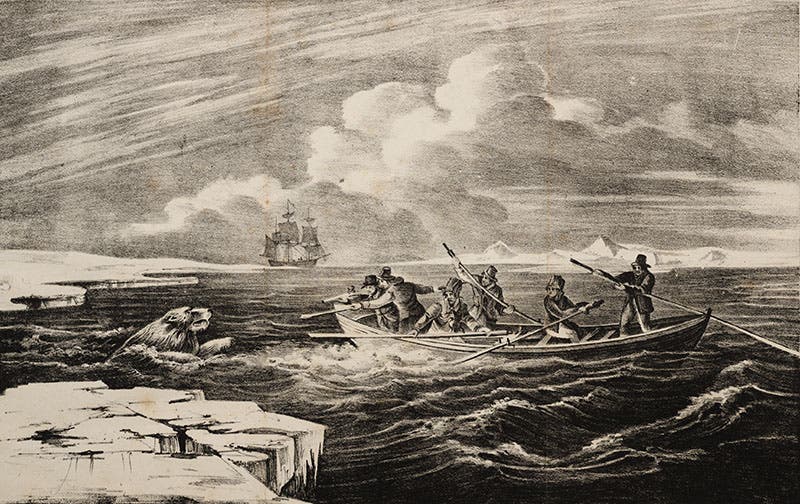

George Manby, in his Journal of a Voyage to Greenland (1822), gave us lithographic impressions of whales, seals, and whaleboats.

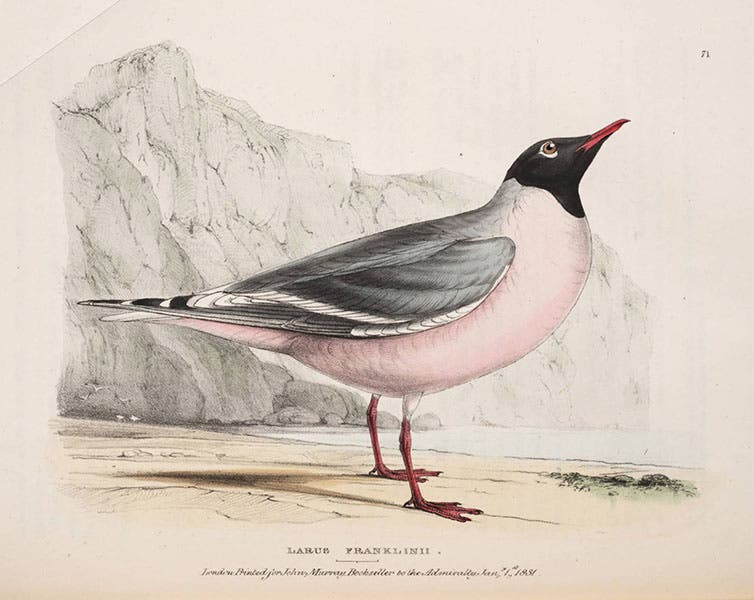

William Swainson was the first to apply lithography to bird illustration, in the second volume of John Richardson’s Fauna boreali-americana (1831; third image). The prints were hand-colored.

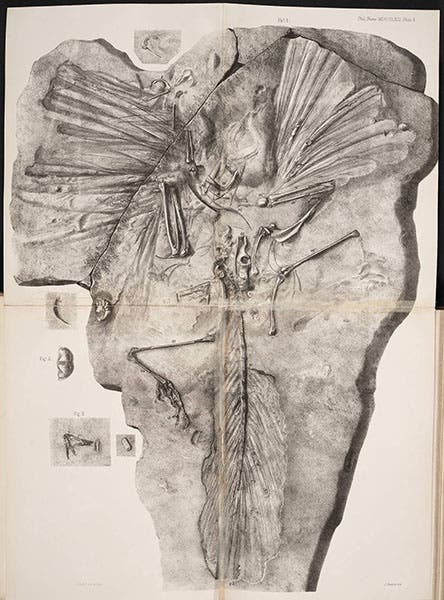

Lithography is at its best in printing images of fossils, since the texture of the lithographic stone serves very well to depict the texture of bone and the matrix in which it is embedded. Richard Owen took full advantage with his illustration of a mylodon skeletal mount, published in 1842 (fourth image).

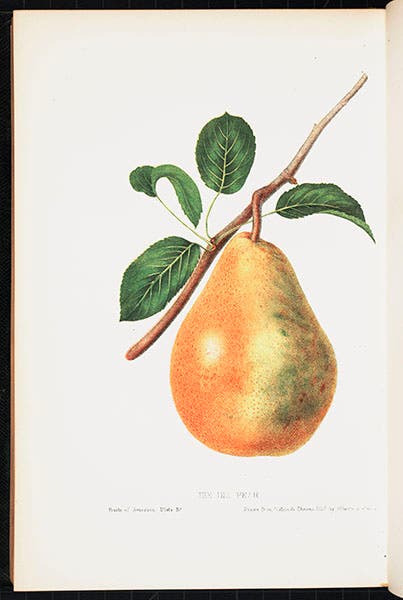

By the 1850s, lithographs were being printed in color, with separated stones for each color; just last week we featured Charles Hovey, whose lithographs of apples and pears are beautifully realistic (fifth image)

The best lithographic stone came from Solnhofen, in Bavaria, which, ironically, is also where many of the best fossils were discovered in the 19th century. So one can often find instances where a fossil, discovered in a piece of Solnhofen limestone, is illustrated by a print pulled from a slab of Solnhofen limestone. Such is the case with the first printed image of the famous Archaeopteryx, the "first bird", which Owen commissioned in 1863 (sixth image).

There are two statues of Senefelder that we know of; one in Berlin, and the other in Solnhofen, which makes perfect sense, for if not for Senefelder, Solnhofen limestone would be sold for building stone and would bring only a fraction of the price that it commands as a print stone. However, we show the one in Berlin, because two putti are amusingly writing Senefelder’s name in reverse, as one would do on a lithographic stone (seventh image).

In 2013, we installed an exhibition, Crayon and Stone: Science Embraces the Lithograph, which featured most of the lithographs here and many others. It is not yet available online.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.