Scientist of the Day - Alvan Clark

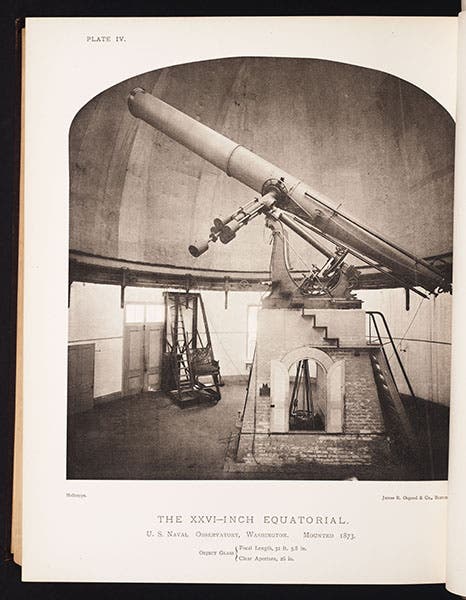

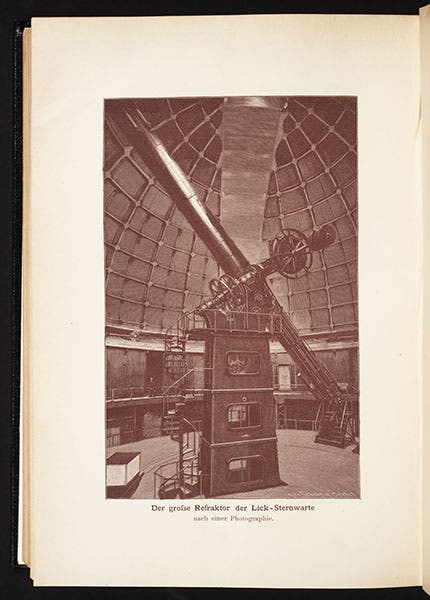

Alvan Clark, an American portrait painter and telescope maker, was born Mar. 8, 1804. Until 1850, Clark painted miniature portraits in his studio in Cambridge, Mass., hundreds of them, of which perhaps 80 survive. Then he got interested in lens grinding, inspired perhaps by the new 15-inch refractor recently installed at Harvard College Observatory. Clark claimed that his lenses were better than those in the expensive telescopes that Americans were buying abroad, but he convinced very few, until the English astronomer William Dawes bought several Clark lenses and praised them highly to astronomers like John Herschel and Lord Rosse. By 1860, the orders began to come in. Clark founded a company with his two sons, Alvan C. and George B., and Alvan Clark & Sons soon began building the largest and finest refracting telescopes in the world. In fact, they built the largest refractor 4 times over, beginning with an 18.5-inch telescope that ended up in Chicago, then a 26-inch refractor for the U.S. Naval Observatory (second image), a 30-inch for the Pulkova Observatory in Russia, and a 36-inch refractor for the new Lick Observatory in California (third image). The company built a fifth record-breaker, the 40-inch Yerkes refractor in Williams Bay, Wisconsin, but Alvan senior had died as the Lick telescope was being completed and before the Yerkes was begun, so we will leave this last one for a different occasion.

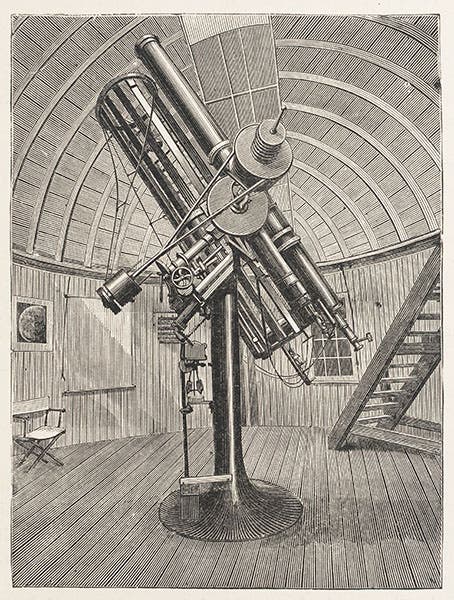

Not all of Alvan's telescopes were record breakers; he made many refractors in the 10-12" range that were perfect for the purpose they had to fulfill. We wrote yesterday about Henry Draper, the New York City pioneer in spectral photography. Draper bought a 12-inch Clark refractor in 1875 and positioned it on the same mount as his 28-inch reflector at his observatory in Hastings on the Hudson, and he found that it had a resolution equal to that of its larger brother (fourth image). In 1880, Draper exchanged the 12-inch refractor for an 11-inch Clark model that was especially made for photography. The returned 12-inch then went to the Lick Observatory, where it served their needs until the 36-inch refractor saw its first light in 1888. Meanwhile, Draper used his 11-inch Clark to take the most stunning photograph to date of the Great Nebula in Orion, which we included in yesterday's article.

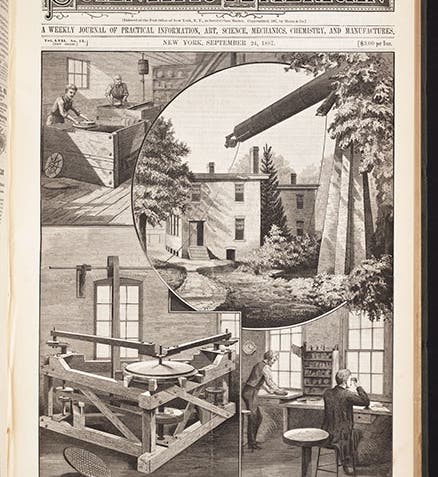

Scientific American put four images of the Alvan Clark & Sons workshop on the cover of its Sept. 23, 1887 issue, to celebrate the men who made the Lick refractor that was about to go into commission (first image). Unfortunately, Alvan died just a month before the issue went to press, barely giving the editors time to change the caption of the interior group photo, to Alvan G. Clark, the late Alvan Clark, and George B. Clark.

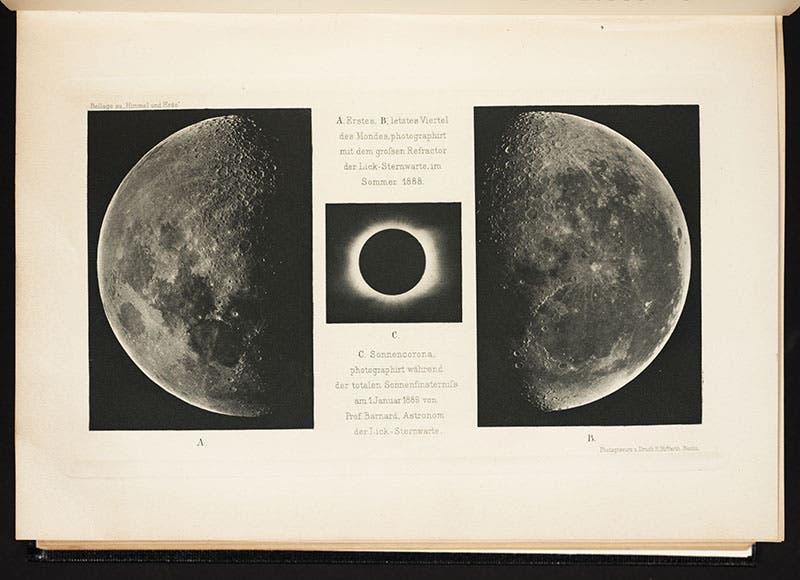

The Lick refractor was soon taking the finest photographs of the Moon ever achieved; we show two of the early ones here (fifth image). We featured several lunar atlases using Lick photographs in our exhibition, The Face of the Moon; we direct you to one, the atlas of E.S. Holden, issued in 1896-97.

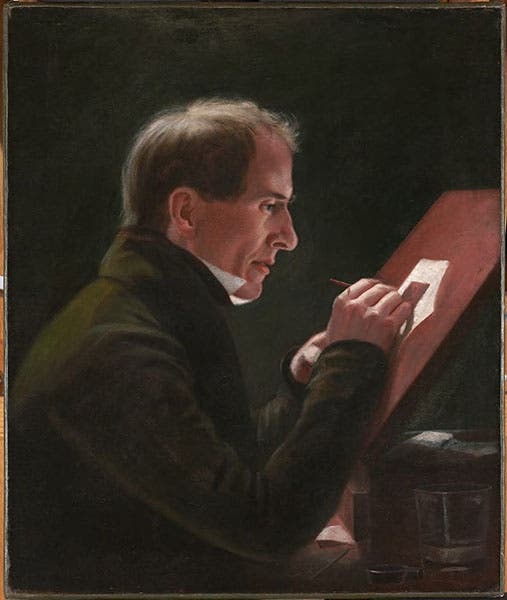

We did not have room to include any of Alvan Clark's miniature portraits, which are highly prized today. But the portrait of Clark that we show, which hangs in the Harvard College Observatory, depicts Clark at perhaps age 40, at work on a miniature at his easel, long before he had any ideas about building giant refractors.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.