Scientist of the Day - Ambrogio Soldani

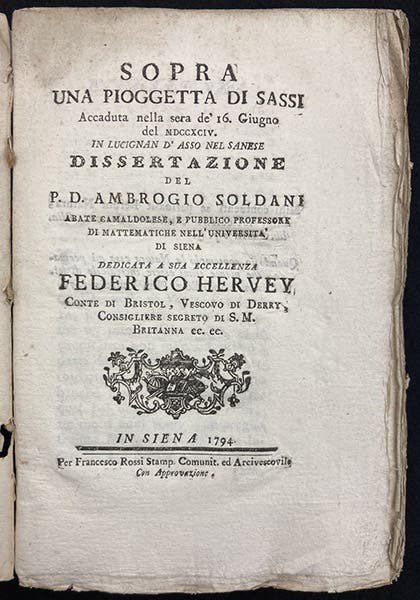

Ambrogio Soldani, an Italian monk and naturalist, died July 14, 1808, at age 72. Nine years ago, we wrote a post on the shower of stones that fell in Siena on June 16, 1794. Soldani was one of the first on the scene, gathering up the meteoritic stones, collecting accounts from witnesses, sending some of the stones to England for chemical analysis, and publishing an account arguing for the extra-terrestrial origin of meteorites, one of the first such arguments to appear in print. Here is that first post.

Although we published that post under Soldani's name, we made no mention of his life and career before 1794, and included no portrait of Soldani. We also did not feature any images from the three books by Soldani in our collections. Today we would like fill in the rest of the blanks surrounding the life and scientific career of Ambrogio Soldani, OSB Cam.

One of the interesting features of Soldani's life is that he was a monk, a member of the order of Camaldolese Benedictines, who were supposedly ascetic hermits, although you would not guess that from Soldani's activities as a naturalist. He became abbot of the monastery in Siena in 1780, which is why he happened to be nearby on the day the stones fell in 1794. Since it is rare to see the postnominal letters "OSB Cam" (Order of the Society of Benedictines Camaldolese) after anyone's name, and especially that of a scientist, it is intriguing to learn that the noted Venetian cartographer Fra Mauro, author of the famous Fra Mauro map of 1459, was also a Camaldolese Benedictine. We featured Fra Mauro once in a post.

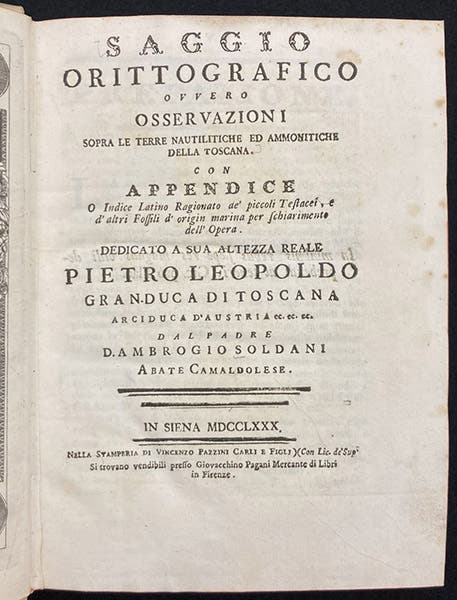

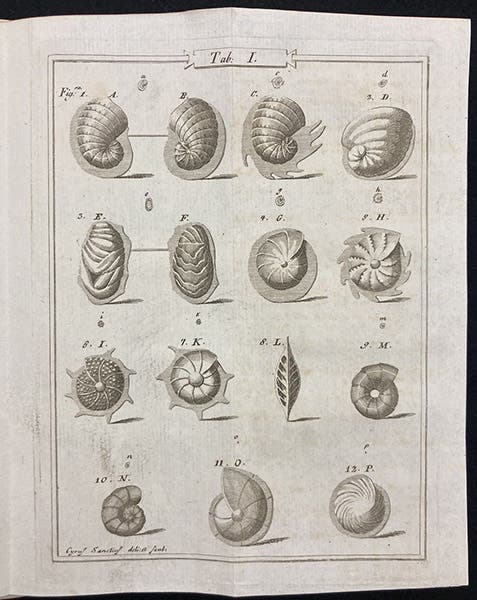

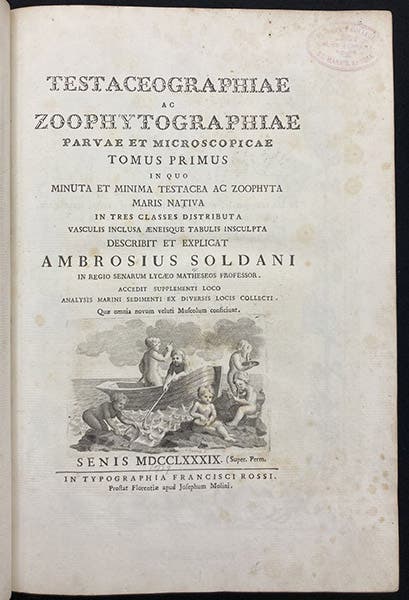

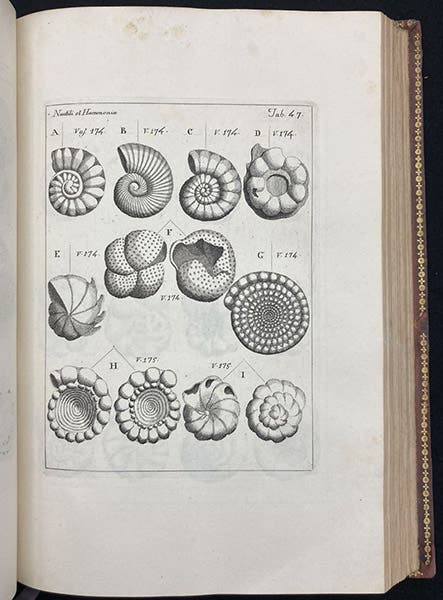

Long before the fall of the Siena stones, Soldani had distinguished himself by being one of the first naturalists to look for fossils with a microscope. Paleontology was just over 100 years old (if we mark its beginning with the work of Nicolaus Steno in 1667), yet the only fossils being collected were the shells and bones one could see with the naked eye. Soldani found that the limestones in Tuscany had microscopic fossils as well, some – tiny ammonites – looking like their larger visible cousins, but others quite new, specimens of what we would call foraminifera. He published a book about these in 1780, with quite a few engravings (and noting his recent promotion on the title page, third image).

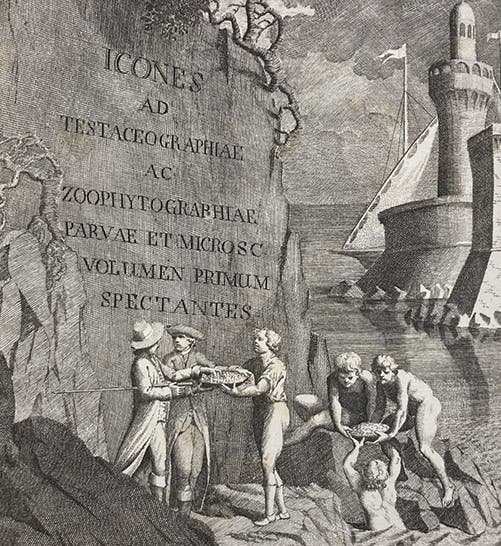

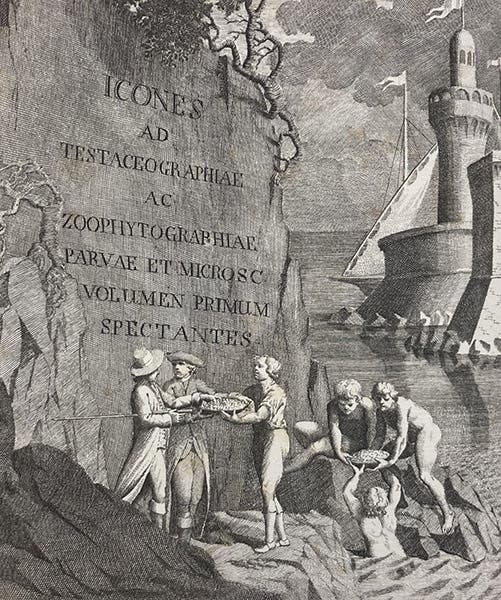

Nine years later, in 1789, Soldani began issuing a much more comprehensive work on microscopic mollusks, both living and fossil, which is in large quarto format, and eventually included a second volume. We have only vol. 1, from which we show a detail of the splendid frontispiece (first image), the title page (fifth image), and one of the engraved plates (sixth image).

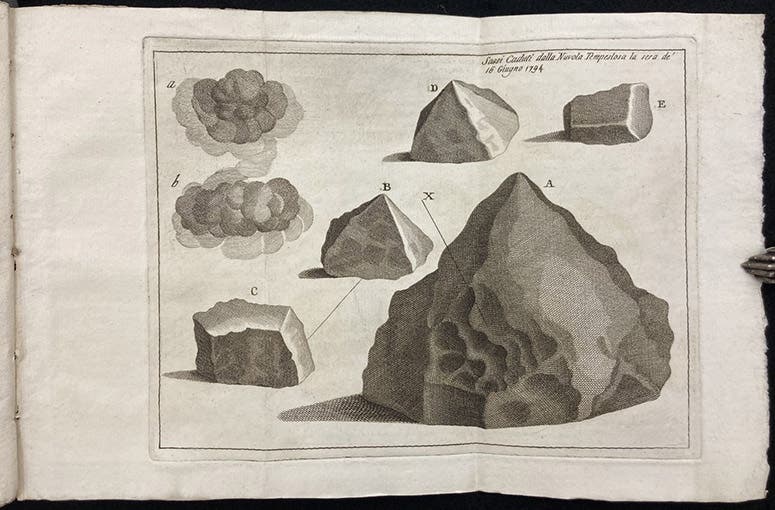

Since we have already discussed Soldani's book on the Sienna stones in our previous post, we will do no more here than show the title page of our copy (seventh image), and the folding plate at the end that depicts some of the fallen stones that Soldani collected (eighth image).

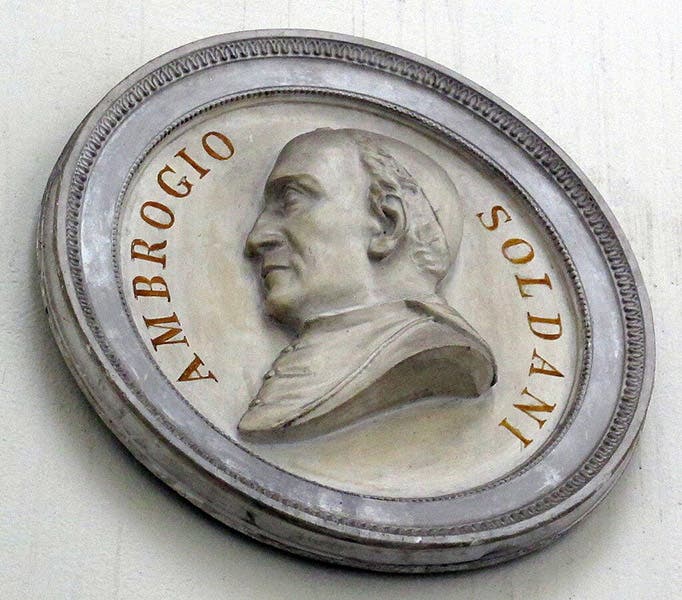

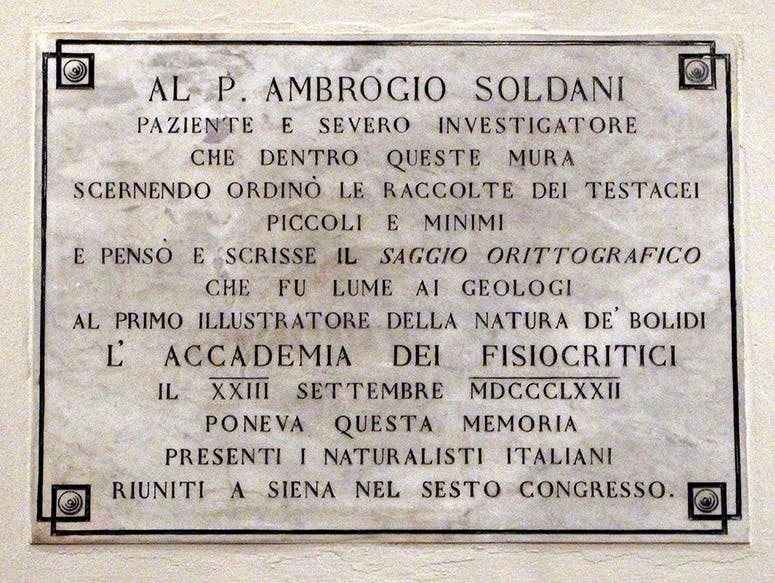

There was a scientific academy in Siena, the Accademia dei Fisiocritici, of which Soldani was secretary for several terms. I do not believe that they had their own meeting place, but ironically, Napoleon "deconsecrated" Santa Mustiola, Soldani's convent, in 1810 (this was after his death) and turned it over to the Academy. They still meet in the church and abbey where Soldani lived. They have honored Soldani’s continued spiritual presence with a portrait medallion and a wall plaque (second and last images). And he is still referred to, in certain circles, as the “father of micropaleontology.”

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.