Scientist of the Day - Amerigo Vespucci

Amerigo Vespucci, an Italian emissary and explorer, was born Mar. 9, 1454. Vespucci was raised in Florence, but around the time that Columbus was setting out on his first voyage, Vespucci was sent to Spain by Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de’ Medici on financial business; he ended up getting involved in organizing voyages to the West Indies for the Crown of Castile. Vespucci then went on several new-world voyages himself; just how many, is a matter of some heated discussion. There were two letters published in Vespucci’s lifetime, known as the Mundus Novus (ca 1504) and the Lettera (1505), that record that Vespucci made four voyages in all, two for Spain and two for Portugal. The authenticity of these letters is widely disputed. In the 18th century, three more letters from Vespucci were found, these in manuscript, and often referred to as the “familiar” letters. One concerned a voyage to Venezuela for Spain, in 1499-1500. The two other letters discuss a voyage down the coast of Brazil in 1501-02. These letters seem genuine, and the voyages they describe, known traditionally as the second and third voyages, apparently took place as described. The first and fourth voyages, described only in the Mundus Novus and the Lettera, probably never took place, at least not with Vespucci aboard.

The Lettera came to the attention of Martin Waldseemüller, part of a cartographic school in Lorraine, who in 1506 was writing an Introduction to Cosmography, which would be accompanied by a world map. Waldseemüller was quite impressed with Vespucci’s letter, so impressed that he appended a Latin translation to his introduction. He also quoted the opinion of Vespucci that the trans-Atlantic lands visited by the Spanish and Portuguese were not an extension of Asia (as Columbus had thought) but truly a “new land”, an unknown fourth continent. Waldseemüller added that, in his opinion, the new continent should be named “America,” the feminine form of Amerigo, to fit in with the three existing feminine continents of Asia, Europa, and Africa.

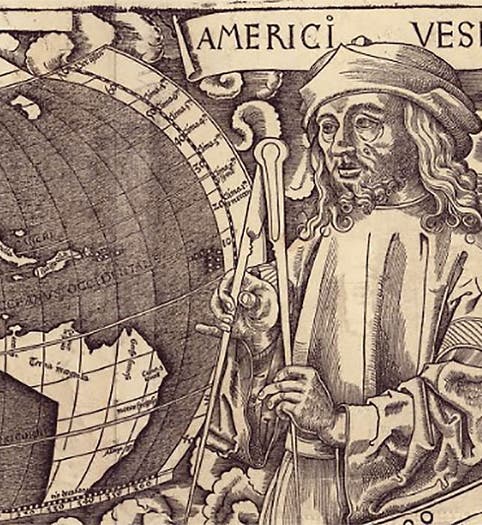

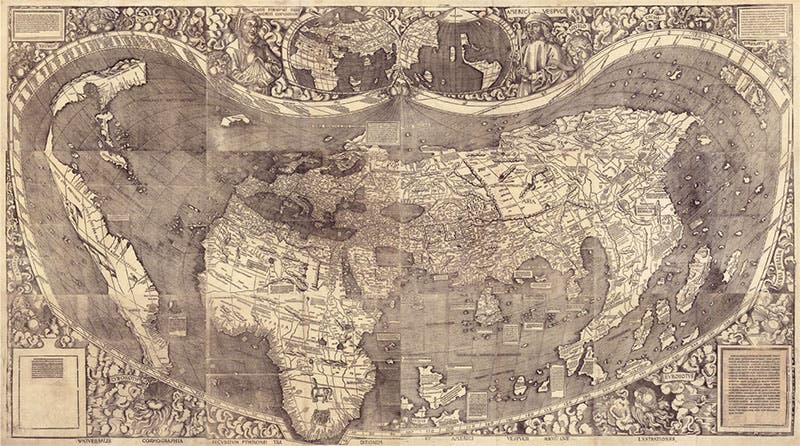

On his world map, Waldseemüller graphically demonstrated his admiration for Vespucci. The map is very large, made up of twelve individual woodcut sheets (second image). The second sheet from the left at the top honors Ptolemy of Alexandria and his map of the world. The sheet just to the right (see detail, first image) includes a portrait of Vespucci, and a map of the other side of the world, with its new continent. On the map itself, at the lower left, the new continent appears as a sliver, but large enough to showcase its new name, America

By the time Waldseemüller’s map was published (1507), Vespucci had returned to the service of Spain and was in charge of instructing all of the prospective Spanish pilots in navigation, which is extraordinary, because if Vespucci was indeed skilled in navigation, he had to have learned it on his voyages, since he had no other training. Vespucci died in Seville in 1512, and as far as anyone can determine, he never learned that his name had been given to the continent that he explored but did not discover.

One thousand copies of the Waldseemüller map were printed, and only one survives; it was bought for the Library of Congress in 2001 and unveiled in 2007, where it is on permanent display in an argon-filled case. For a view of the map�’s display case at the Library of Congress, and a detail of “America,” see our earlier entry on Waldseemüller.

There are a few portraits of Vespucci in existence, but most were executed after his death, and it is hard to know if any capture his actual appearance. There is a statue of Vespucci in the walkway beneath the Uffizzi in Florence (third image). And one of our portrait books, that by Isaac Bullart (1682) includes Vespucci, although I would not wager as to its verisimilitude (fourth image).

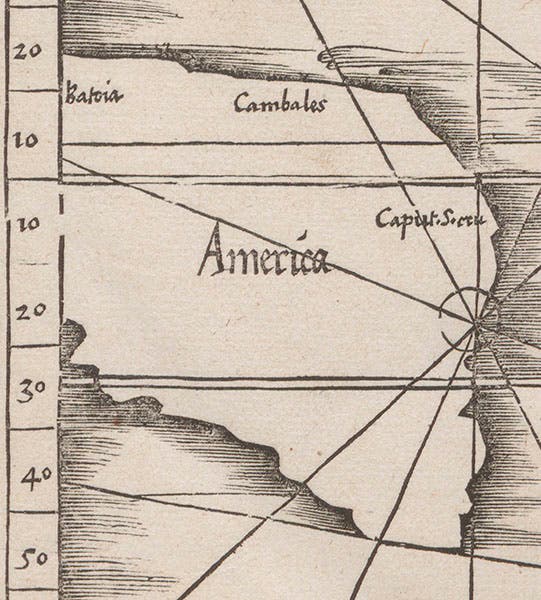

The earliest bit of Vespucciana we have in our library is a world map of 1522 by Laurent Fries, included in his edition of Ptolemy’s Geographia of 1525 (fifth image). The map is roughly based on that of Waldseemüller, and includes the label “America” for the new fourth continent, as we see in a detail (sixth image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.