Scientist of the Day - Andre Michaux

André Michaux, a French botanist, died Oct. 11, 1802, at age 56. He had been born in Satory, France, on Mar. 7, 1746, and he spent the years from 1785 to 1796 botanizing in the new United States, making trips to the Carolinas, Florida, up into Canada, and west into Kentucky. He sent thousands of specimens back to France, including 60,000 trees, intended to replenish the French forests that had been depleted by centuries of shipbuilding. Michaux published a book about the oak trees of America in 1801, just before he died, which is a splendid publication, with 36 engraved plates by the Redouté brothers. We wrote about Michaux and his oak trees in an earlier post, six years ago.

Today we use the occasion of a new book on Michaux to talk about his relationship with the American Philosophical Society (APS) in Philadelphia. When Michaux first came to the United States, the fledgling republic had been victorious in the war against England but did not yet have a Constitution or a President. Michaux headed first for New York City, where he set up a garden along the Hudson River Palisades in New Jersey. But he did not like the money-grubbing culture of New York City, and he was relieved when he visited Philadelphia and found there a city that held learning and culture in high regard, just like in Paris. He met William Bartram (John Bartram, William’s equally-famous father, had died in 1777) and was impressed by their garden along the Schuylkill River, and the Franklin tree that he saw there.

Michaux then travelled to the Carolinas, where he set up a second botanical garden in Charleston, South Carolina, which he used as a base for collecting in Florida and Georgia. His expenses were paid by the King of France. After the French Revolution began in 1789, and the King was executed in 1791, finances became strained, and he was pretty much on his own for several years. What he really wanted to do was travel out west, perhaps as far as the Pacific coast, and collect the new plants and trees that he was sure to find there. But he would need funds.

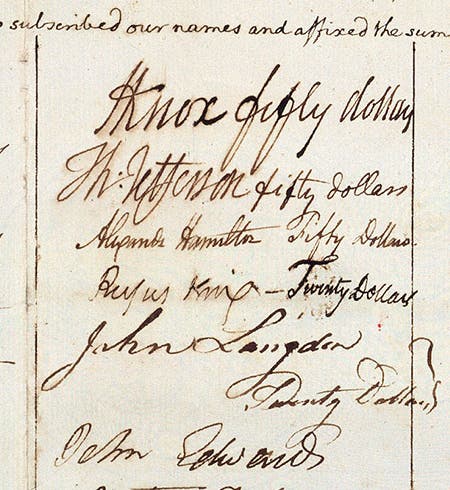

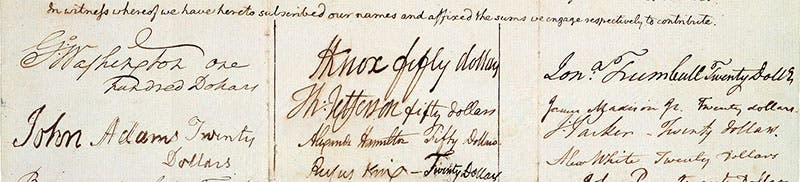

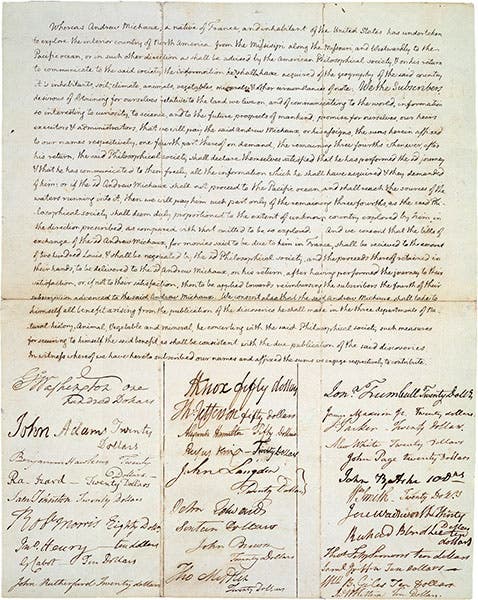

Back in Philadelphia, late in 1792, he talked with Thomas Jefferson about his hopes to go west. Jefferson was at the time secretary of state for the government of George Washington, the Constitution having been ratified in 1789 and Washington elected president. Philadelphia was the nation’s capital, for the time being. This was ten years before Lewis and Clark, so there had been as yet no scientific expeditions into the West, and Jefferson was enthusiastic. Michaux had an excellent track record for exploration, and even though he was French – enthusiastically French, with no wish to be an American – this seemed to be a perfect opportunity for the young American Philosophical Society (re-founded in 1769) to support a truly worthwhile project. So Jefferson took the lead, drew up a document describing the goals of the Michaux expedition, and left space at the bottom for pledges. Washington pledged $100, a year's wages for most people, and signed his name, followed by John Adams, who pledged a more prudent $20. They were followed by a battery of senators, and then Jefferson, who pledged $50, then more congressmen, including James Madison, who was willing to kick in $20 as well (first image). There were 30 signatures in all, including four people who were or would be President of the United States. The document still survives; it goes by the name of the Michaux Subscription List, and it is one of the treasures of the APS, the kind of special document that you bring out for distinguished visitors. It is, as far as anyone knows, the only surviving document that contains the signatures of four U.S. presidents.

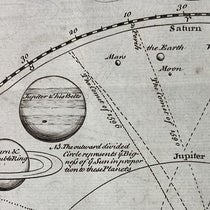

The document (you can see the entire parchment in our second image) is much more famous than the expedition itself, because the Michaux expedition never got underway. When Jefferson wrote out a directive of expedition goals (as he would later do for Lewis and Clark), Michaux began to have misgivings, fearing that the Michaux expedition was turning into an APS expedition, with different aims from his own. And then he was waylaid in mid-1793 by the new French minister to the U.S., Edmond-Charles Genet, and persuaded to secretly take charge of organizing Frenchmen in Kentucky to form an army that George Rogers Clark, now a disgruntled frontiersman, could use to attack the Spanish stronghold of New Orleans, which was controlling access to the Mississippi River. The new book we mentioned, published just last month, The Scientist Turned Spy: André Michaux, Thomas Jefferson, and the Conspiracy of 1793, by Patrick Spero, former Librarian at the APS and soon to be their new CEO, is mostly focused on the events of 1793-4, and Jefferson's knowledge of, and surprising silence concerning, this near-traitorous venture, although we don’t get to Michaux's "spy" role until we are 170 pages into his life, which to me, was more fascinating than the events in Kentucky, which went nowhere, like the expedition west.

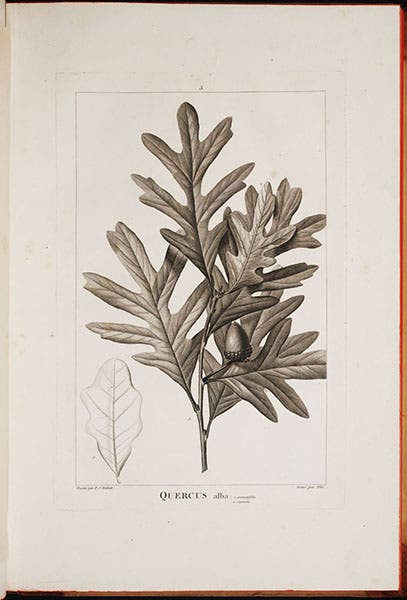

When Michaux finally returned to France in 1796, he was urged by colleagues to publish something – he had always been much more interested in collecting and discovering new species than writing – so he quickly put together his Histoire des chênes de l'Amérique (Natural History of the Oaks of America, 1801), and someone persuaded Pierre-Joseph Redouté, with a little help from brother Henri-Joseph, to provide the illustrations, which are gorgeous, considering that they show only leaves and acorns. In addition to the three plates we included in our previous post on Michaux, we add one more here, the white oak, but we add it twice, including a detail (third and fourth images). Well before his book appeared in print, Michaux sailed off with the Baudin expedition to Australia in 1800, left the voyage at Mauritius in 1801, shifted to Madagascar, and died there of a fever on this day in 1802.

There is only one portrait of Michaux in regular use, and it is an ugly one, so I refer you to Wikipedia, if you must see it. Michaux had a son, François-André, who accompanied his father on his later journeys and became an excellent botanist himself, and he had his portrait painted by one of the Peale’s in Philadelphia. We will have to do a post on the younger Michaux someday (we have one of his books), if only so that we can display a good portrait of a Michaux. And the son looked enough like his dad that their portraits are often confused.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.