Scientist of the Day - Andrea Mantegna

Andrea Mantegna, an Italian artist, died Sep. 13, 1506, at the age of about 75. Mantegna grew up in and around Padua, not far from Venice, and learned the art and craft of painting there. When he was apprenticing, the technique of perspective was filtering through a second generation of Italian artists, percolating out from its home in Florence. Perspective – the technique of capturing a three-dimensional scene on a two-dimensional surface – was invented by Filippo Brunelleschi sometime before 1416, and disseminated by Leon Battista Alberti, in his treatise on painting (1435). We have written posts on both individuals, but we focused on their contributions to architecture; we need to do additional posts on both to discuss the origins of perspective. The first artist to employ Brunelleschi’s techniques was Masaccio, about whom we have written an essay, and the potential of perspective for artists was demonstrated by Piero della Francesca and many others. Perspective became an artistic technique, but it originated from geometry, and was one of the great gifts of science to Renaissance art, utterly transforming the nature of the painted picture.

Another significant development in art of the 1450s was naturalism, the study of nature by artists, for the purpose of enriching their paintings. Pisanello was one of the first to draw birds and wildlife and then "people' his paintings with dogs and deer and hares in a very naturalistic manner. We should do a post on Pisanello as well.

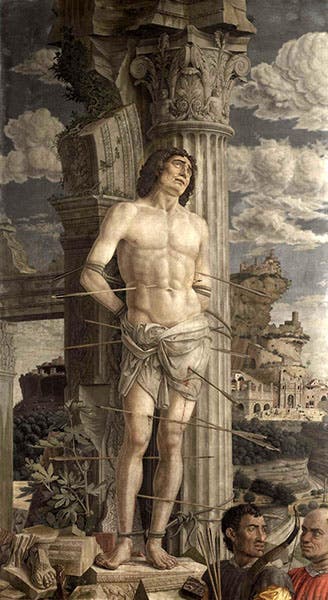

A third development in early Renaissance art was closer attention to the human body. Artists did not yet do their own dissections – that would not come until Leonardo da Vinci – but they did exhibit a keener interest in accurately rendering the human form, especially the male body, from the 1460s on.

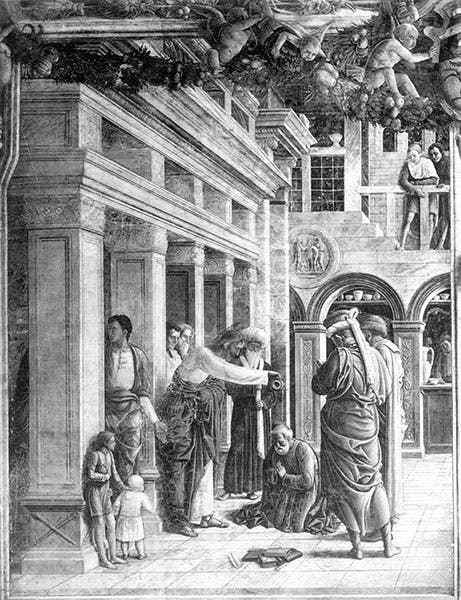

Mantegna brought all three developments together in his paintings. He was a master of perspective, and was one of the first to experiment with low vantage points, as in his frescos on the martyrdom of St. James in the Ovetari chapel in the church of the Eremitani in Padua (we show black and white photos, because the chapel was destroyed in 1944 by a bomb - a mis-directed American one!). The left panel, showing the “Baptism of Hermogenes by St James” (second image), is very skillfully laid out with a low horizon; the “Trial of St. James,” (third image) which was right next to the “Baptism” and shared the same vanishing appoint, is included because the soldier leaning against the column at left is thought to be a self-portrait of Mantegna.

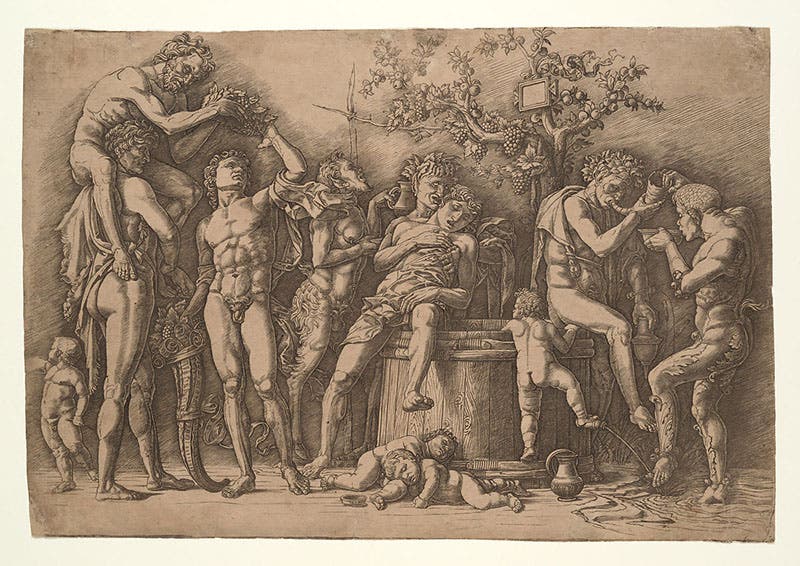

Mantegna also liked to draw and paint the nude human form. He did several paintings of the martyrdom of St Sebastian, who was shot full of arrows and was customarily shown semi-nude (fourth image). This one is in the Louvre. The Museum of Modern Art in New York has a lovely engraving by Mantegna of a bacchanal (before1475) that shows a variety of nudes in every possible posture (fifth image).

Mantegna’s interest in providing realistic natural backgrounds for his Biblical scenes is evident in many of his works; we especially like the Agony in the Garden (1455-56), now in the National Gallery in London, where the rocks are beautifully rendered, as are the many rabbits, included by Mantegna as emblems of resurrection (first and sixth image). Its naturalism aside, it is also a wonderful composition, with the road sinuously winding from the sleeping apostles in the foreground back to Judas, leading the Roman soldiers (and some rabbits) to Jesus. And the angels at left, surfing on their cloud, may not be naturalistic, but they certainly are delightful.

You might notice that one of the apostles in the foreground of the Agony in the Garden is foreshortened, lying down with his feet pointing out at the viewer. Mantegna was one of the first Renaissance artists to bring his skill at perspective to bear on the problems of depicting the human form when it is at a steep angle to the picture frame, as with the apostle here. His most celebrated attempt at foreshortening the human body came in a late painting, the Lamentation over the Dead Christ (1490), now in the Brera Art Gallery in Milan (seventh image). The feet of Christ, emerging dramatically from the picture space with the torn flesh of the stigmata, attest to the torment on the cross in an unprecedented way.

Finally, Mantegna liked to use his skill at perspective to tease the viewer. Between 1465 and 1474, Mantegna decorated a room in the Ducal Palace of Mantua, for the Duke, Ludovico Gonzaga, whom Mantegnanow served as court painter. The various wall frescoes are realistic enough, but when one looks up at the ceiling, the reality is only apparent (eighth image). We see a cupola open to the sky, a cupola that is not really there. Peering down over the balustrade are various maidens, and scattered around the inside of the cupola are assorted putti, properly foreshortened so that they look ready to do real mischief on the viewers below (ninth image). There is even a large flowerpot, poised precariously on a rod that looks none too stable. Many artists at the time were painting trompe-l’oeil ceilings for palaces and churches, but very few had the skill to include foreshortened humans (and putti) without destroying the illusion

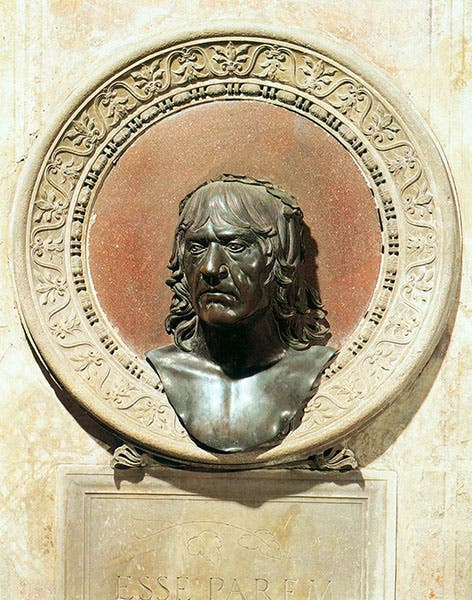

Aside from the destroyed self-portrait in Padua, the only other representation of Mantegna is another self-portrait, this one a bronze relief in Sant’Andrea in Mantua (1504-06), executed in the last years of life. He does not look too pleased with the reality of growing old.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.