Scientist of the Day - Andrew Smith Hallidie

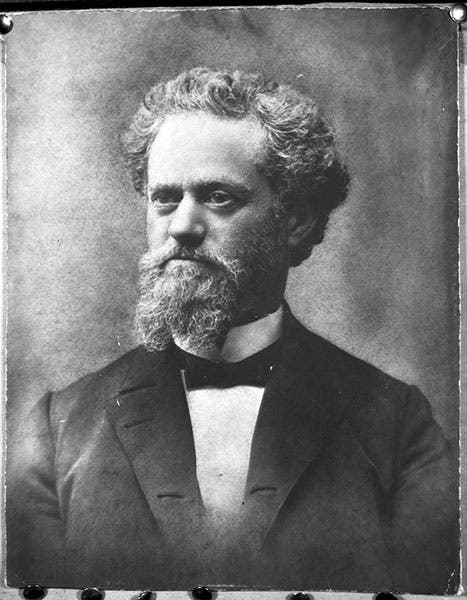

Andrew Smith Hallidie, an American inventor and entrepreneur, was born Mar. 16, 1836, in Scotland. He came to California with his father in the 1850s to oversee some gold-mining interests; his father returned to Scotland, and Hallidie stayed where he was. He built bridges in California, and using a process invented by his father, started manufacturing wire rope, which at the time was non-existent in California. He also became a U.S. citizen. Hallidie invented an overhead wire tramway for hauling ore out of mines, which probably gave him the idea for his great invention, the cable car.

In 1870, San Francisco had only horsecars, and they struggled with the hilly streets. Hallidie wondered if he could run a continuous wire cable either under or over the streets and find a way to attach (and detach) a streetcar to it. The cable was no problem – the real difficulty was coming up with a "gripper" – something that could grab a moving cable and hold on for dear life until released. Hallidie came up with one, probably with considerable help from his chief engineer, William Eppelsheimer, since Hallidie had no real training in mechanical engineering. Around 1870, Hallidie decided to tackle Nob Hill, where the incline on Clay Street was over 15 degrees, with a short cable-powered street railway,

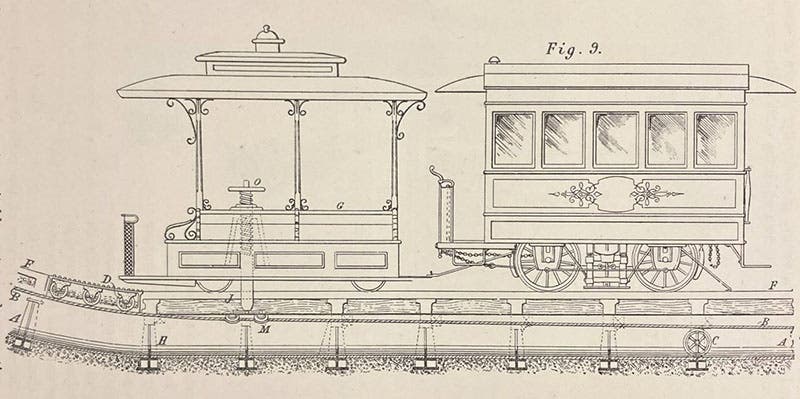

Section diagram of the grip car and trailer of the Clay St. Hill R.R., showing the location of the grip (the screw-like mechanism) that engages the moving cable beneath the roadway, wood engraving in A Treatise upon Cable or Rope Traction, as Applied to the Working of Street and Other Railways, by J. Bucknall Smith, 1887 (Linda Hall Library)

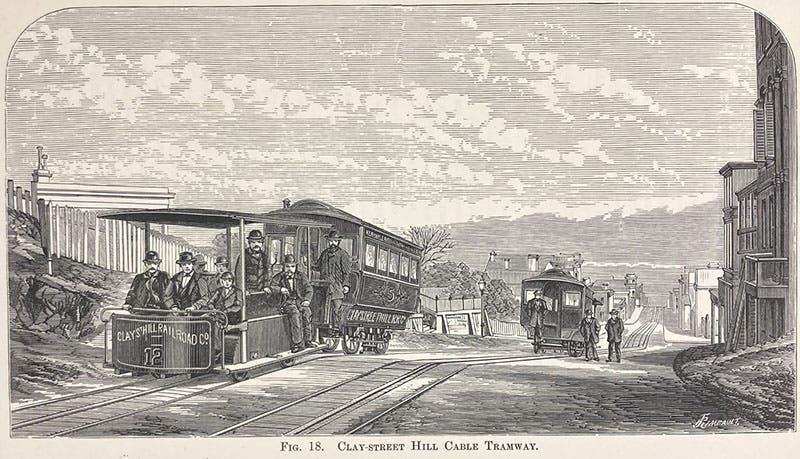

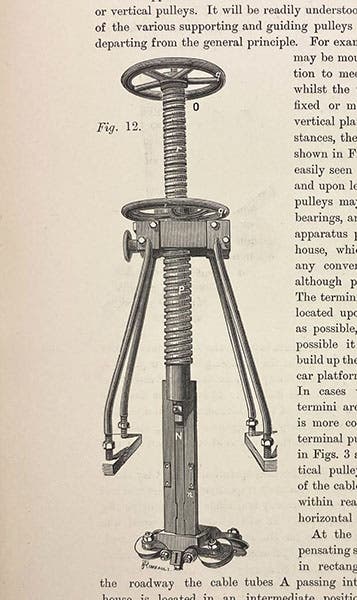

Hallidie put a steam engine in a power plant at the top of the hill and ran an endless moving cable through a channel beneath the rails (one side of the cable moved up the hill, and the other down, accommodating two sets of rails). The cable could be accessed by a streetcar through a narrow slot between the rails (third image). The gripper Hallidie used was a heavy screw that tapered to fit through the slot below, where it held four pulleys that would grab the cable when the lower wheel on the screw was turned (fourth image). The car with the grip screw was called the “dummy” or the grip car (we prefer the latter), and it pulled a covered car called the trailer, for the passengers.

The “grip” of the Clay St. Hill R.R. drive cars, with 4 pulley wheels at the very bottom that engaged the moving endless cable, wood engraving in A Treatise upon Cable or Rope Traction, as Applied to the Working of Street and Other Railways. (Rev. and enl. from "Engineering") by J. Bucknall Smith, 1887 (Linda Hall Library)

On this day, Aug. 2, 1873, in the early morning hours, Hallidie ran his first streetcar with a few passengers up and down Nob Hill. (the deadline for a successful trip was Aug. 1, but the city did not cancel the contract for this bit of tardiness). The Clay Street Hill Railroad officially opened to the public on Sep. 1, and it was a great success, as riders flocked to pay the fare to ride up and down the hill.

Soon, cable cars were built by rival companies on other San Francisco hills, using different styles of "grippers,” including the now familiar long lever. Hallidie played no role in these further developments, but Eppelsheimer did, leading many to think that Eppelsheimer was the real brains behind the first cable car. But Hallidie was the mover and shaker, and he got rich from the Clay Street line and from his patents, and so he is generally credited with being the father of the San Francisco cable car. One of his grip cars, no. 8, was displayed at the 1893 Columbian World's Exposition in Chicago, which was 20 years after the first run of the Clay Street Hill Railroad. That car refused to disappear and is now on display in the San Francisco Cable Car Museum, which (I think) is in the very building on Nob Hill that once housed the steam engine for the Clay Street Hill line (seventh image).

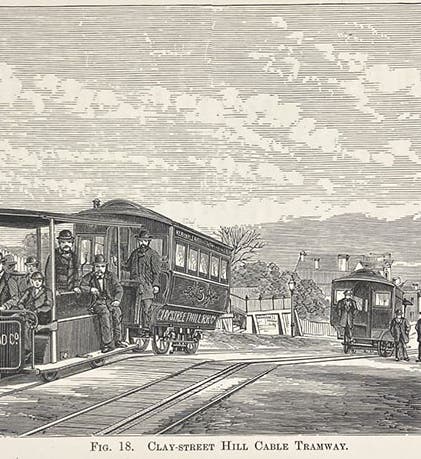

There are quite a few photographs that show the Clay Street Hill Railroad in action, many in the archives of the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency (fifth and sixth images). From these photographs, wood engravings were made and used in publications such as one in our collections, A Treatise upon Cable or Rope Traction, as Applied to the Working of Street and Other Railways, by J. Bucknall Smith, 1887, the source of several of our images. It is apparent from these photographs and engravings that although passengers were supposed to ride in the more comfortable trailer, many preferred to ride the dummy and chat with the grip.

After the electric streetcar was introduced in 1888, the cable car gradually became obsolete and disappeared in other cities, but not in San Francisco, where the three surviving lines are a top tourist attraction, and a National Historic Landmark.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.