Scientist of the Day - Archibald Garrod

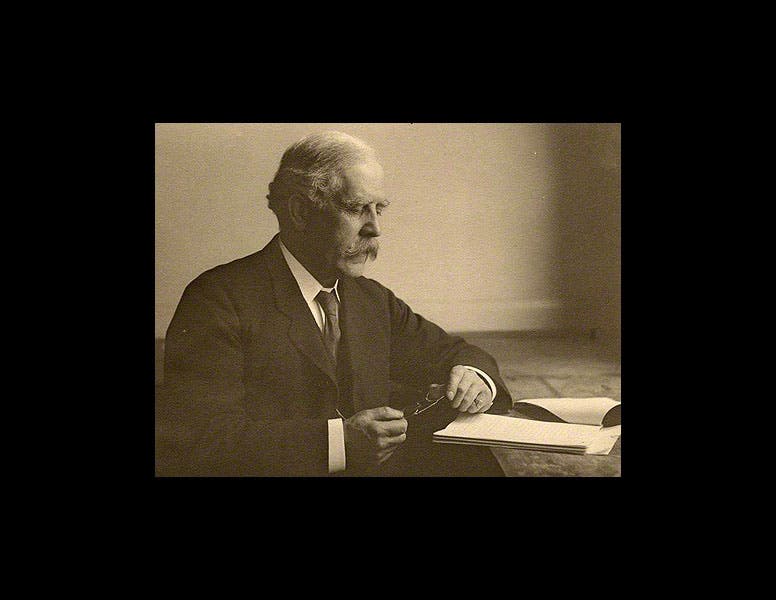

Archibald Garrod, an English physician, died Mar. 28, 1936 at the age of 78. Just after 1900, Garrod began studying a group of families that suffered from a rare disease called alkaptonuria, or black urine disease, named after its most obvious and distressing symptom, urine that turns dark when it contacts the air. His study coincided with the rediscovery of Mendel's laws of inheritance in 1900, and Garrod realized that alkaptonuria behaves like one of Mendel's recessive genetic traits. Garrod guessed that people with alkaptonuria have a defective gene that produces a faulty enzyme that interrupts an important metabolic pathway. This was the first recognition of the possibility that genes direct the assembly of enzymes, and more specifically, that each gene codes for one enzyme. Over the next few years, Garrod discovered three more metabolic diseases that behave like recessive traits, including albinism, and he announced the existence of inherited metabolic diseases in the Croonian lectures of 1908, delivered to the Royal College of Physicians in London and published in 1909 as Inborn Errors of Metabolism (second image). At a time when Mendel was still not well understood, the lectures had little impact, and even though Garrod republished his book in expanded form in 1923, it was generally not appreciated that he had established a direct connection between Mendelian genetics and Darwinian evolution. Garrod never received the Nobel prize for his work, which he certainly should have, especially since George Beadle, who re-proposed the “one-gene, one enzyme” hypothesis in 1941, did receive the Nobel prize for what was essentially a confirmation of Garrod’s original discovery.

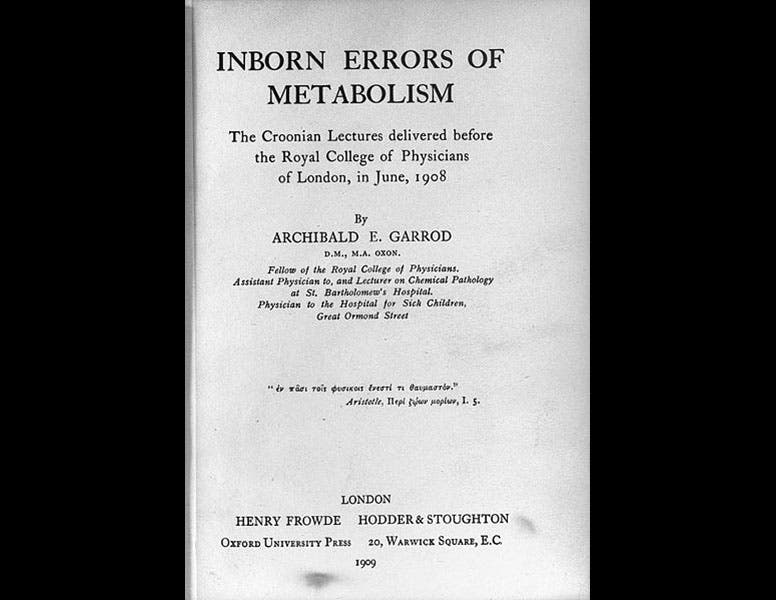

But Garrod probably didn’t care, because he suffered a much greater loss than most of us can comprehend, losing all three of his sons in the First World War, two in combat and one in the great flu epidemic of 1919. The three are commemorated by plaques in the Church of St Andrew in Melton (third image). Archibald did have a daughter, Dorothy, who was a distinguished archaeologist, becoming the first woman professor at Cambridge in 1939; she must have been a source of comfort and happiness for her father. Still, to lose three of your children when you are in your sixties must just rip the heart out of you. Even though Garrod succeeded to the prestigious Osler Professorship at Oxford in 1920 and was regarded as the premier physiologist in Britain from then until his death, I am sure it was a rare day when he counted his blessings. He deserved much more happiness than that.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.