Scientist of the Day - August Macke

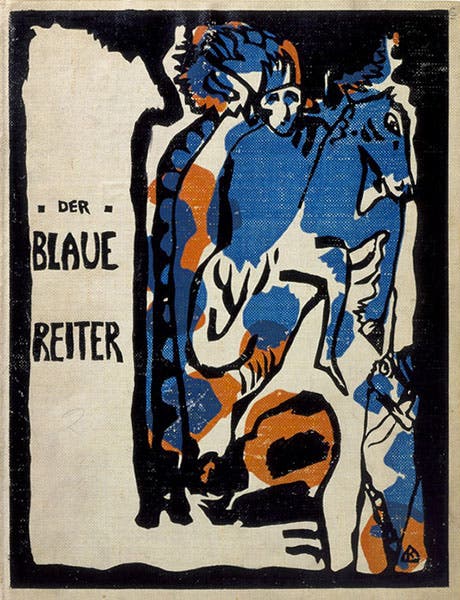

August Macke, a German expressionist painter, was born Jan. 3, 1887. Macke, with Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc, was one of the founders of Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider), a loose collective of radical artists that was named after an almanac edited by Marc and Kandinsky (second image). Two years ago we wrote about another German expressionist, Lyonel Feininger, who was a contemporary of Macke, and there we made the case that artists should occasionally be included in a science blog. Feininger, for example, was fascinated by modern technology – high-rise buildings, steam ships, bridges – and by the uneasiness that machine technology can invoke in humans. I tried to argue that scientists and artists, especially those of the avant-garde, are working toward the same goal – trying to make sense of the world – although they have different ways of approaching the problem.

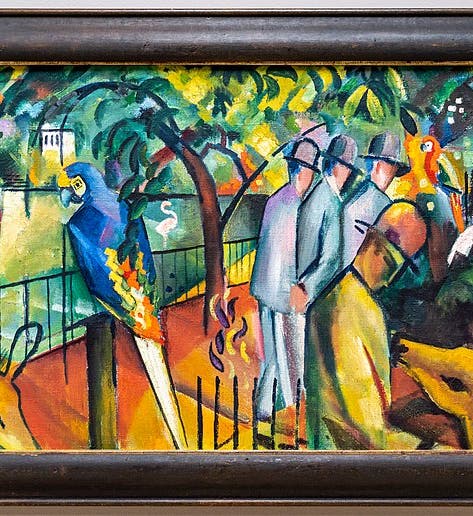

An argument for including Macke is tougher, because, except for his two paintings of a zoological garden (first image), and a still life or two, Macke didn't really take nature for his subject. He preferred to paint people, usually in a park-like setting, as with the wonderful Promenade (1913, third image), and if he was preoccupied by anything, it was color, which he treated the way cubists treated space and line, as something to be experimented with and manipulated.

Macke’s Four Girls (1913; fourth image) is another favorite of mine, and I am sure that most people who gaze upon it (in the Museum Kunstpalast, Düsseldorf) do not relate it to 20th-century physics. But when I look at the striking colors of this painting, I cannot help but think of Niels Bohr, who that very year (1913) was explaining the colors of chemical spectra by applying the new quantum theory to the atom. I know there was absolutely no connection between Macke and Bohr, but one might well wonder whether Macke’s experiments with color were any less scientific than Bohr’s. One of them ended up with a painting, the other an equation, but who is to say which was more instructive in helping us understand how we see the world.

We include two more of Macke’s paintings here, because we can, and we will only point out that the lady in the Large Bright Shop Window (1912. fifth image) has a cubist perspective that is almost mesmerizing.

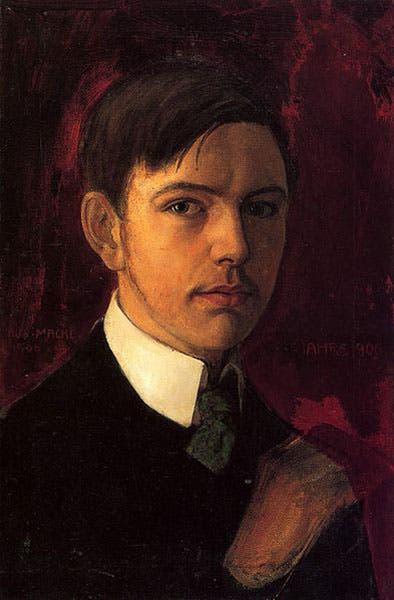

We conclude with a self-portrait of Macke (seventh image), showing him as a young man, which is appropriate, because his life was snuffed out in the first year of World War I, in 1914. He was only 27 years old. It is tragic that an artist with so much promise was denied the opportunity to develop a mature style. What if Bohr had died in 1914? It is hard to imagine what path physics would have taken in the succeeding 30 years.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.