Scientist of the Day - Austen Henry Layard

Austen Henry Layard, a British archaeologist, died July 5, 1894, at the age of 87. In 1845, Layard began investigating tells in northern Iraq, in an area he called Kouyunjik . which we now spell Kuyunjiq, but for which we prefer the name Nineveh. Nineveh was the last great city of the Assyrian Empire. We call Layard an archaeologist, because that is the term we now use for someone who digs up antiquities, but there was no archaeological ethos in Layard. A more accurate term would be plunderer. His goal was to remove as many art objects as possible and send them back to England at the lowest possible cost. And he was very successful in his activities. He retrieved several pair of colossal winged lions and bulls (we now call them lamassu) from Nineveh and Nimrud and shipped them home; some ended up in the British Museum, with one mis-matched pair (lion and bull) eventually going to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. He also published a very successful book, Nineveh and its Remains (1849) about his adventures. We told and illustrated this part of Layard's life story in a post four years ago, at which time we promised to return to Layard someday to discuss his second book about his second trip to Nineveh. Today is that day.

Layard returned to Nineveh in 1849, while his first book was still in publication, and excavated there until 1851. He discovered what he took to be the ruins of the Palace of Sennacherib, and also some large bas-reliefs of Dagon, the fish-god who figures in several Babylonian creation stories. He returned in 1851 and set about writing Discoveries in the Ruins of Nineveh and Babylon, which was published in 1853. We have two copies of this book in our collections, but we drew our images from copy 2, still in its original binding, for reasons explained below.

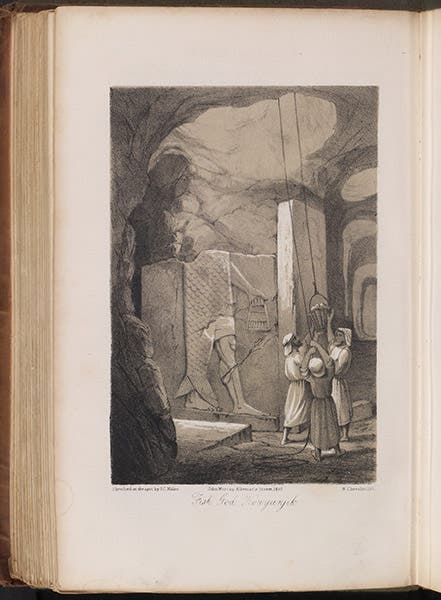

The book is illustrated with line engravings and some text wood engravings, but the most interesting images are the tinted lithographs, where one lithographic stone prints the primary image in black, and one or more additional stones are used to add color, usually in shades of beige or rust. These were just coming into vogue for travel books, and the Pacific Railroad Reports in the United States would soon adopt the tinted lithograph as the medium of choice, inserting hundreds of them in the 13 printed volumes (see, for example, our posts on John Newberry and Edward Beckwith). I am not sure when the tinted lithograph came into wide use in England, but Layard’s book was certainly one of the first to make use of tint stones.

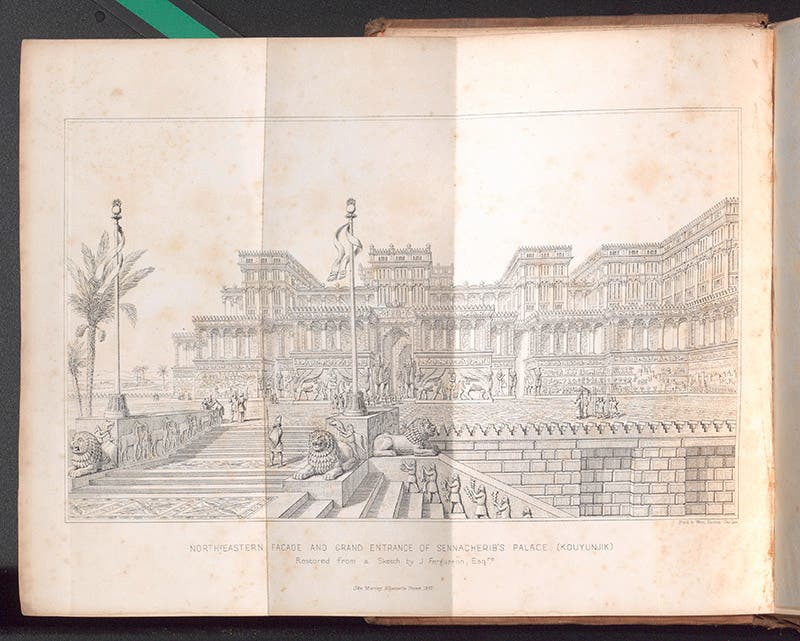

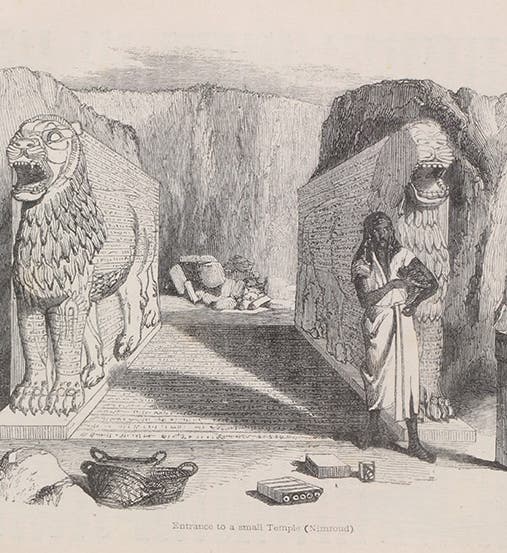

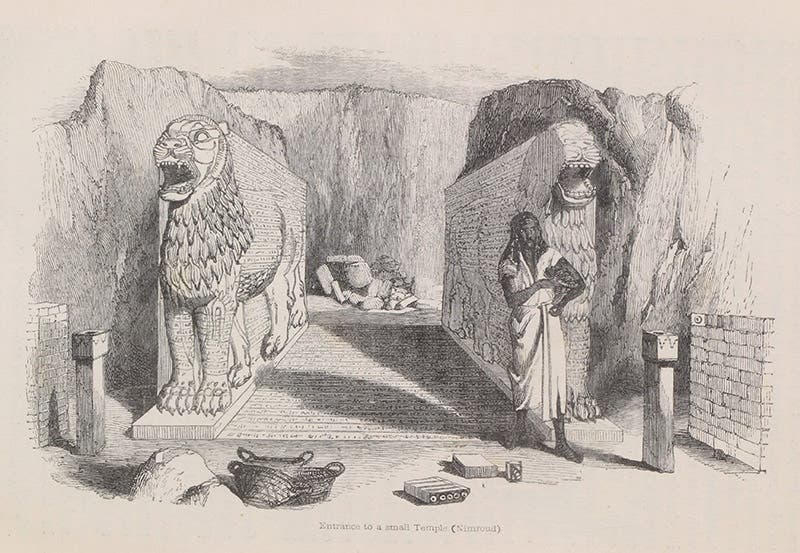

We include two tinted lithographs here from Discoveries in Nineveh. One shows a chamber containing a relief carving of the Nineveh fish god (Nineveh in fact means fish), and we show the entire page that contains this print (fourth image, above). For the other, a plate that depicts another excavation at Kouyunjik, we show a close detail, so that you can see the pebbly texture that only a lithographic stone can provide (fifth image, just above). One other image we include is an engraving, which shows how the lamassu customarily stood on either side of a palace entrance (first image). Another is the large folding frontispiece for the book, providing the reader with a pen-and-ink restoration of the palace of Sennacherib, one of the last of the great Assyrian kings (sixth image).

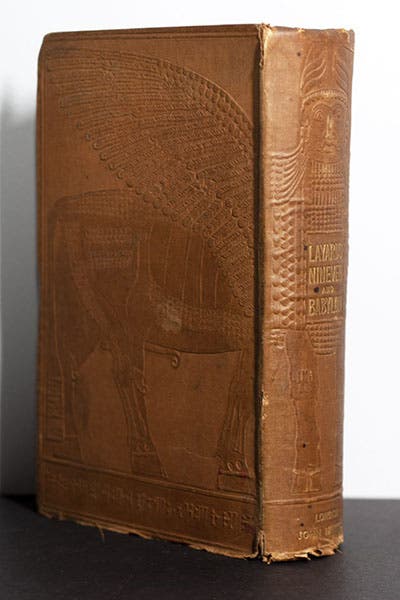

We also show the rear cover and the spine of Discoveries in Nineveh, because it is unusual. The binding is tan cloth (cloth bindings were a recent invention in England), stamped with the figure of a winged lamassu, with the wings on both covers and the head on the spine. Stamped cloth bindings were brand new – for all I now, this is the first, and if not, it is certainly the most elaborate. There is even a cuneiform inscription stamped on both covers, at the bottom. You cannot see the inscription in our photo, but you can see it very well in the zoomable photo in Jeremy Norman's entry about the book on his excellent History of Information website.

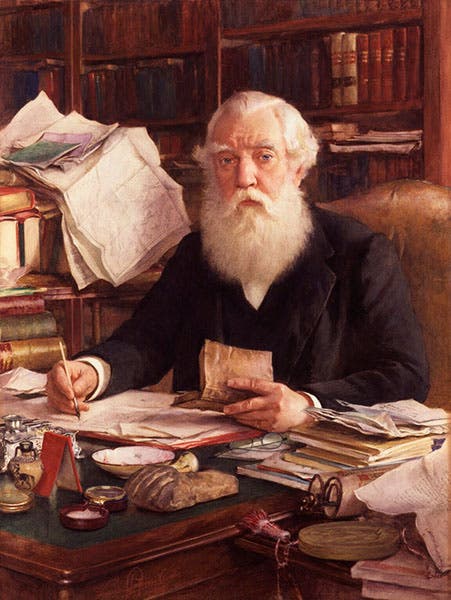

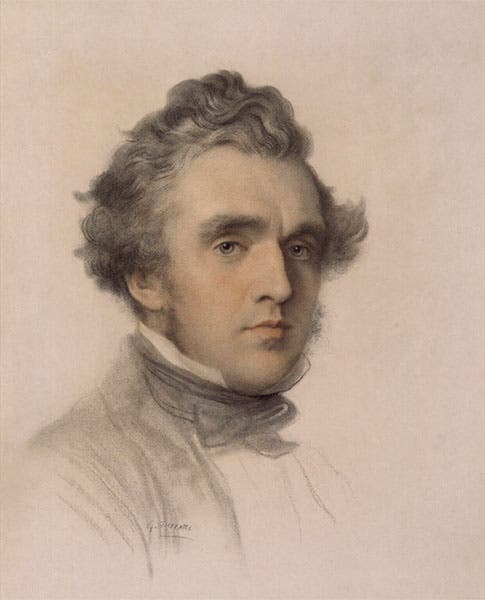

In our first post on Layard, we included a portrait of Layard from1858. For this occasion, we provide two more portraits – one, a chalk drawing, showing him in 1852, just before Discoveries was published (second image), and the other a full-blown oil portrait, painted in 1891. The second is not really relevant to Layard's activities in the 1850s. But it is such a wonderful portrayal of a former adventurer turned politician and diplomat, but still anchored in the glorious days of his youth, that we wanted to include it here. Like the chalk portrait, it is in the National Portrait Gallery in London (eighth image, below).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![Detail of a tinted lithograph with the caption, “Excavations at Kouyunjik [Nineveh],” to show the lithograph texture, Austen Henry Layard, Discoveries in the Ruins of Nineveh and Babylon, 1853 (Linda Hall Library)](https://preview-assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/65f6882d-63bb-4c04-a93d-b9083c33b774/layard5.jpg?w=800&h=596&auto=format&q=75&fit=crop)