Scientist of the Day - Benjamin Martin

Benjamin Martin, an English science teacher, instrument maker, and popular science author, died on Feb 9, 1782, at the age of 75-77. He was raised on a farm in Surrey and apparently had little access to formal schooling, but he read voraciously, and by the time he was in his mid-twenties, he had started a school in Sussex, and soon he was writing textbooks of a sort for use in his and other similar kinds of schools. These were very popular, and although we don't have any of those early publications, they went through many editions

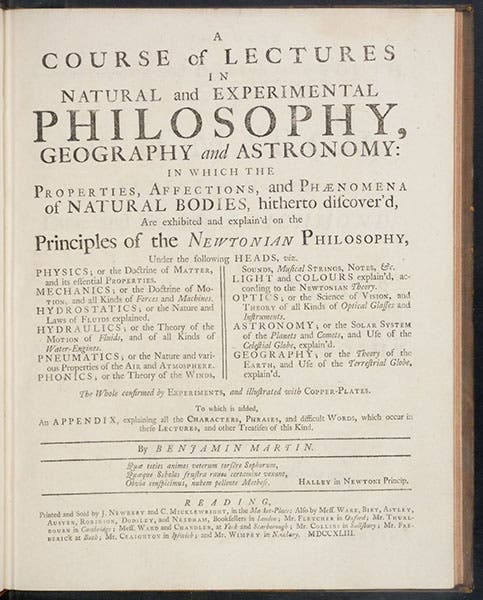

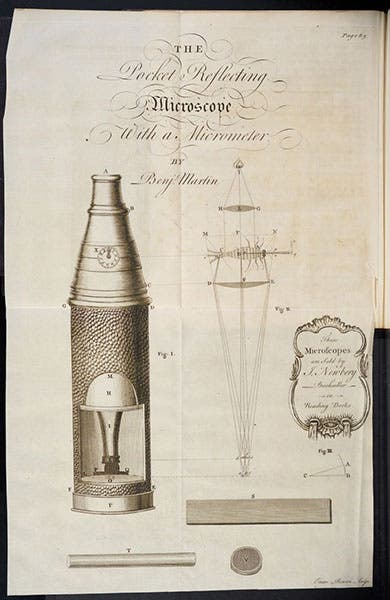

In 1742, Martin moved to Reading, on the Thames near London, and there he published two substantial quartos, both of which we have in our collections. One was called Micrographia nova (1742), about two new microscopes he had invented, one a pocket reflecting microscope. The other was A Course of Lectures in Natural and Experimental Philosophy (1743). It is this latter book that will engage out attention for the rest of this post, for it is a recent acquisition, purchased in 2024, and it is fun on occasion to show a book we have just bought, and explain why we did so.

A Course was intended for people who had attended or would be attending Martin's lectures. It covers matter theory, projectiles, falling bodies, electricity, magnetism, pneumatics, with frequent reference to experiments that had been performed for the audience. The content is very similar to that of the course books of John Desaguliers, who had begun teaching Newtonian physics in London in the 1710s and whose lectures had been published in the 1720s, first by others, then by himself,

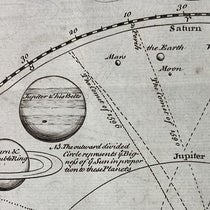

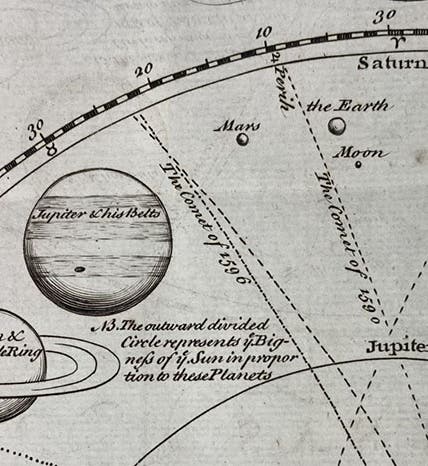

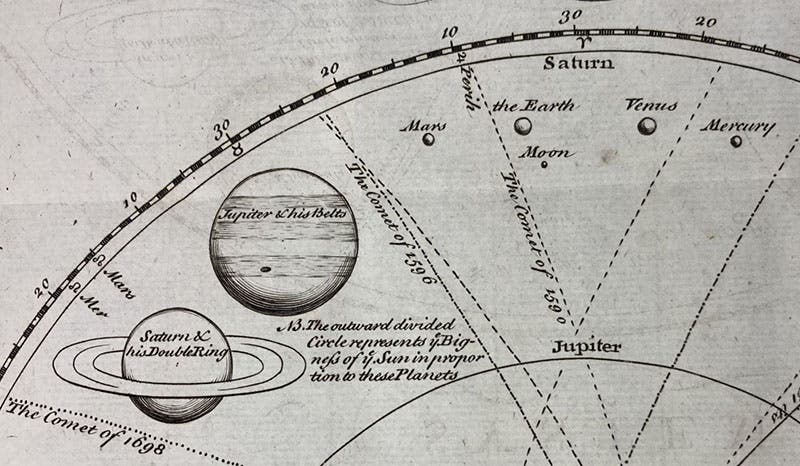

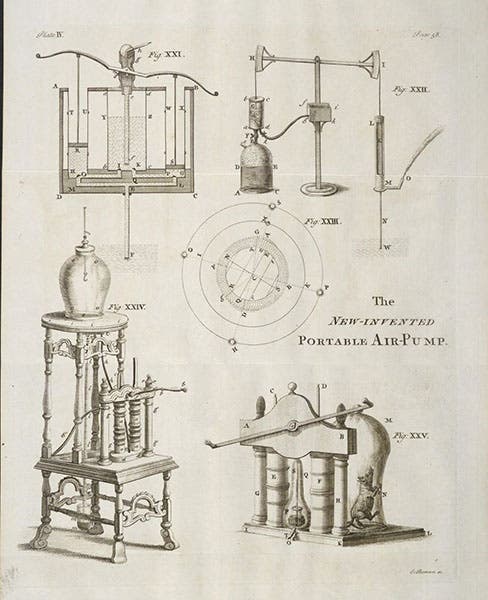

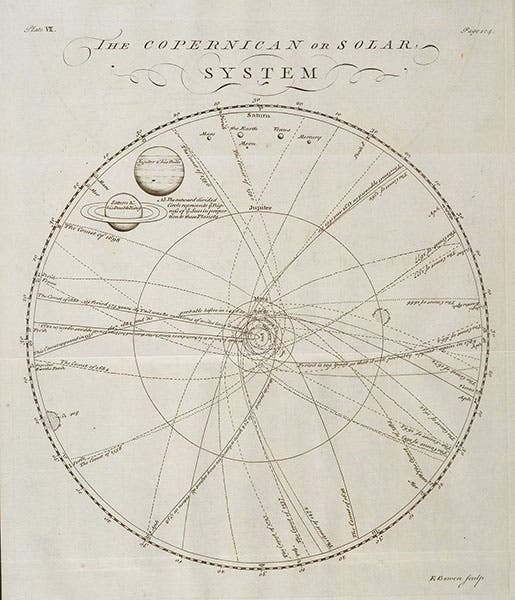

Where Martin made his mark was with his engravings. Desaguliers had included many plates in his books, but they mostly contained small line diagrams. Martin included only a dozen or so engravings, but they were large, often shaded, and some had to be folded several times to fit into the quarto-sized book. He showed his two newly invented microscopes (fourth image), drawings of air pumps (fifth image), and a diagram of the solar system. This latter fold-out engraving (sixth image) is quite something in its detail, as it shows not only the planetary orbits to scale, and the planets themselves to scale (first image), but the paths of all the comets tracked by astronomers for the past 200 years. Incidentally, in our detail of the planets to scale (first image), the circular scale around the entire diagram corresponds to the size of the Sun at the same scale.

All these engravings were printed on thick wove paper and all are intact and untorn, which played a factor in our decision to acquire. They are also mostly unique, unlike those of Desaguliers, which were usually copied from standard sources. So Martin’s book on Newtonian physics is not like anyone else’s book on Newtonian physics, and we like books like that.

The large solar system diagram was also an attraction for us. It happened that a teacher named Thomas Wright, living up in Durham, started publishing large solar system diagrams in 1742 and again in 1750. No one really knows where he got the idea. It is possible that Martin’s engraving gave Wright the idea. Or possibly Martin borrowed the notion from Wright. If someone wants to investigate the possibilities, we have the engravings to compare.

![The second half of the path of the comet of 1531,1607, and 1682 [Halley’s comet], predicting its return in 75 years, or 1758, rotated detail of “The Copernican or Solar System,” folding engraving, A Course of Lectures in Natural and Experimental Philosophy, by Benjamin Martin, p. 104, 1743 (Linda Hall Library)](https://preview-assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/5463618c-9391-46c7-945c-0ed1d8c241b1/martin8.jpg?w=800&h=451&auto=format&q=75&fit=crop)

The second half of the path of the comet of 1531,1607, and 1682 [Halley’s comet], predicting its return in 75 years, or 1758, rotated detail of “The Copernican or Solar System,” folding engraving, A Course of Lectures in Natural and Experimental Philosophy, by Benjamin Martin, p. 104, 1743 (Linda Hall Library)

The many comet paths shown on the solar system diagram were all real historical comets. I call your attention, via two details (last two images, above), to a single comet that appeared in 1531, 1607, 1682, and possibly 1456, which might, therefore (continuing on to the second detail, last image) have a period of 75 years or so, and might return in 1758. And indeed it would, confirming the predictions of Edmond Halley. Martin had no doubt about it, in 1743.

Martin eventually moved to London and published quite a few more books and journals, some of which we have in our library. He seems to have been successful, but it is likely that his teaching income dried up as he aged and ran into health problems. Since his teaching drove his book sales, that source of income ran low as well. By the early 1780s, he was bankrupt. In 1782, he was dead, possibly the result of a botched suicide. He left no money, but he had an extensive collection of instruments, which generated a thousand pounds at the bankruptcy auction. Everyone went away happy, except poor Benjamin, who was buried in a cemetery on Fleet Street, without a grave marker.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![The first half of the path of the comet of 1531,1607, and 1682 [Halley’s comet], detail of “The Copernican or Solar System,” folding engraving, A Course of Lectures in Natural and Experimental Philosophy, by Benjamin Martin, p. 104, 1743 (Linda Hall Library)](https://preview-assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/2fb3810f-7418-4832-becc-9f315795cddc/martin7.jpg?w=800&h=381&auto=format&q=75&fit=crop)