Scientist of the Day - Charles Goodyear

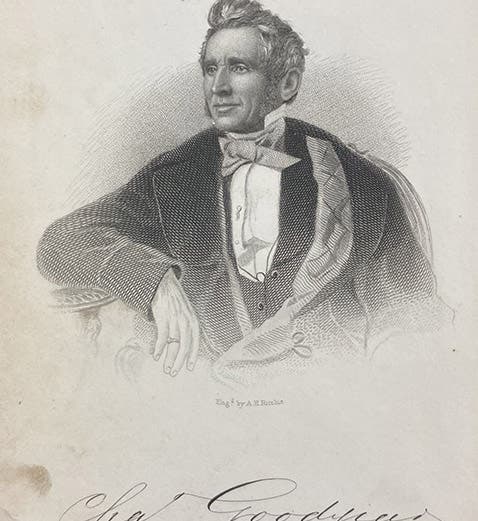

Charles Goodyear, an American self-taught chemist and inventor, was born Dec. 29, 1800, in New Haven, Conn. His father was a merchant, and Charles started out in the hardware business in Philadelphia and Naugatuck, Conn. It was about 1834 that he became interested in the problem of India rubber. It was a material of immense potential, if only someone could figure out how to keep it from melting in the summer and cracking in the winter. His business ruined by the Panic of 1837, Goodyear turned to experimenting with rubber, working in many places, including Boston, New York City, Woburn, Mass., and Naugatuck, supported by investors and, when they lost faith, family and acquaintances. He came close several times to making rubber commercially viable, as when he treated it with nitric acid, but none of these stabilizations turned out to be permanent. Finally, in 1839, he discovered that heating rubber with sulfur effected a permanent change. He supposedly discovered this by dropping a sulphurated blob of rubber onto a hot stove and observing that it did not melt (second image).

It took Goodyear 5 years to perfect his process and secure a U.S. patent in 1844. Meanwhile, the Englishman Thomas Hancock discovered vulcanization on his own (or perhaps with the help of a few Goodyear rubber samples circulating through England and France), and he received a British patent a few weeks before Goodyear got his, effectively cutting Goodyear off from a British patent of his own.

Goodyear’s famous patent no. 3633, the one awarded in 1844 for vulcanization, was not accompanied by a patent model, but a few months earlier, he patented a device for applying vulcanized rubber to fabric, and the model for patent no. 3462 does survive, in the National Museum of American History (third image).

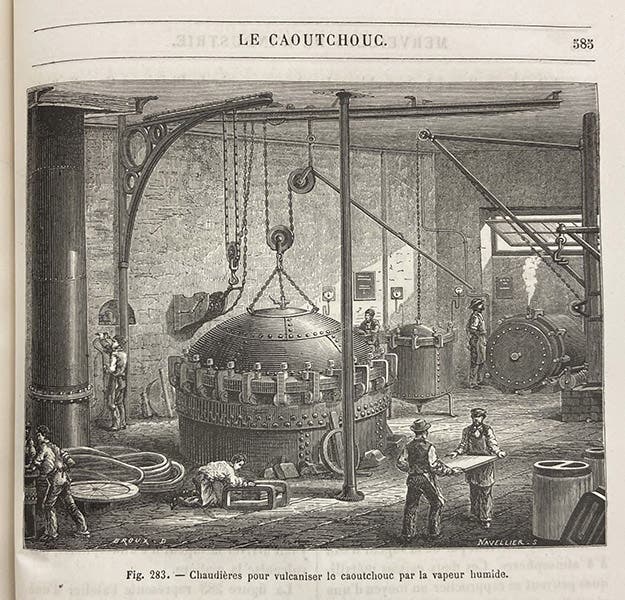

The invention of vulcanization certainly rubberized the world, and rubber factories sprang up around Naugatuck and then around the world (fourth image), but Goodyear did not profit from this, wrapped up as he was in patent infringement suits. He was also in continually poor health, from years of experimentation with nitric acid and caustic alkalis. He died in New York City on July 1, 1860, not yet 60 years old.

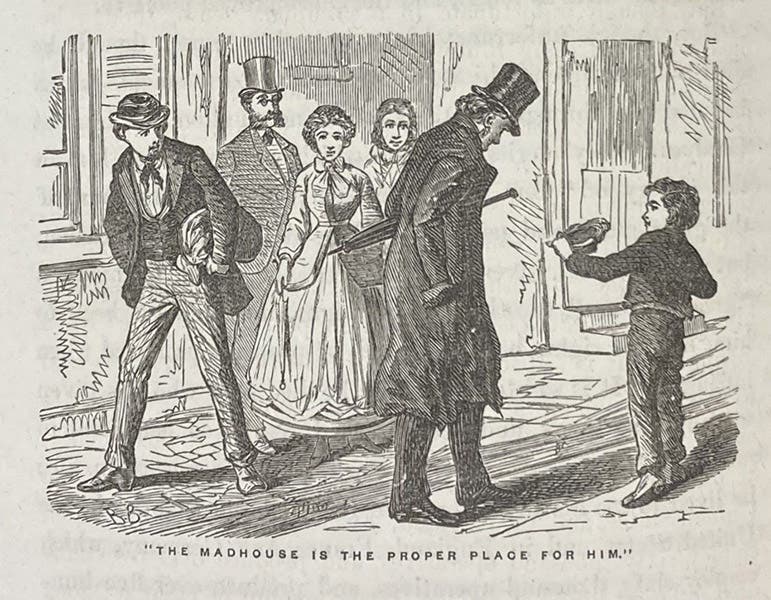

“The Madhouse is the Proper Place for Him,” an impoverished Charles Goodyear in his rubber coat wandering the streets of New York, wood-engraved tailpiece in Great Fortunes and How They were Made; or, The Struggles and Triumphs of our Self-Made Men, by James D. McCabe, p. 300, 1871 (Linda Hall Library)

Goodyear spawned his first biography in 1866, the frontispiece of which provided our portrait (first image), and he merited chapters in most books on great American inventors of the late 19th century, of which there were many. We have a book called Great Fortunes and How They were Made; or, The Struggles and Triumphs of our Self-Made Men, by James D. McCabe (1871), filled with rags-to-riches stories of the likes of Samuel F.B. Morse and Cyrus Field. McCabe justified the inclusion of Goodyear by explaining that while he never got rich himself, his invention made the fortunes of many others. McCabe ended his chapter with a wood-engraved tailpiece showing Goodyear wandering the streets of New York City, wearing his India-rubber raincoat and looking for food, with the caption: “The Madhouse is the Proper Place for Him” (fifth image).

Many people associate Goodyear with the Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company in Akron and the Goodyear blimp, but Charles had nothing to do with founding that firm. It was established in 1898 and, in a burst of patriotism (or guilt), the directors named the company after Charles. In 1939, on the centennial anniversary of the discovery of vulcanization, Goodyear (the company) feted 2000 guests at a dinner in Akron and unveiled a bronze statue of Goodyear, sculpted by Walter Russell. The statue still stands, in its own little park in Akron.

Goodyear was buried along with many siblings and children in Grove Street Cemetery in his home town of New Haven, in a grave that looks neither contemporary nor especially attractive, so I chose not to show it here, but you may find it on Goodyear’s page on findagrave.com, along with a photo portrait different from the one we included here.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.