Scientist of the Day - Christian Konrad Sprengel

Christian Konrad Sprengel, a German naturalist, died Apr. 7, 1816, at age 65. Sprengel earned his living as a teacher in a Lutheran School in Spandau, but he was an avid amateur botanist. In 1787, Sprengel began a series of experiments on pollination in flowers. At the time, it was known that plants reproduce sexually, and plant sexuality had been used by Linnaeus as the basis for his classification of plants. But the subject still made many people uncomfortable; few investigations had been made into the process by which pollen is handled by plants, and hardly anyone realized the vital role played by insects in pollination.

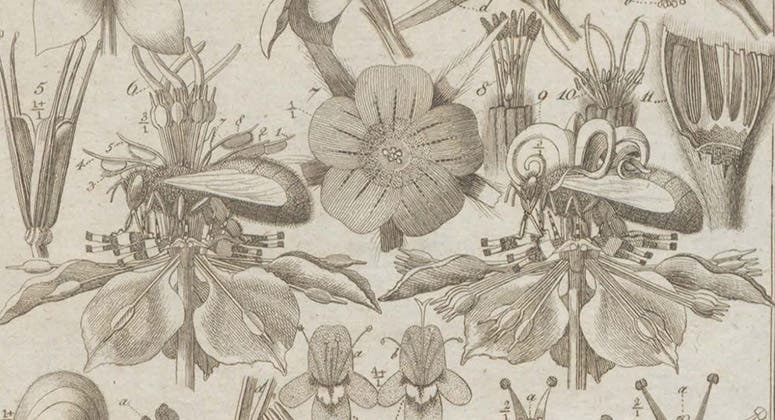

Sprengel recognized the intimate fit of insect to flower. He noted that many flowers are constructed to allow only one particular species of insect access to nectar, and thus to pollen. He also noticed that flowers are often so arranged that they cannot be fertilized by their own pollen. Sprengel published the results of his extensive investigations in what is now recognized as a milestone work in the history of science: Das entdecke Geheimnis der Natur im Bau und in der Befruchtung der Blumen (The Discovered Secrets of Nature in the Construction and Fertilization of Flowers, 1793). The work has 25 plates with over a thousand figures, displaying the various flower mechanisms that ensure pollination.

Let’s look at one of the plates in his book, plate 24 (third image). In a detail of the center of this plate (fourth image), you can see, at the left, a bee taking nectar from a flower, and the anthers just above it are wiping pollen onto its back, which the bee will carry away. At the right in this same detail, the anthers, their pollen gone, are now bent out of the way, and another bee, with pollen on its back from a different flower, is rubbing against the pistils, which are now curled down to pick up the pollen. Ah, the ingenuity of nature!

A bee receiving pollen from a flower (left), and a different bee donating pollen to that same flower (right), detail of third image, engraving based on drawings by Christian Konrad Sprengel, in his Das Entdeckte Geheimniss der Natur im Bau und in der Befruchtung der Blumen, plate 24, 1793 (Linda Hall Library)

Sprengel's book had little impact for 70 years, because these plant mechanisms really only make sense in the light of Darwinian natural selection, and so Sprengel spent the rest of his life (23 more years) in obscurity. But when Charles Darwin examined the pollination mechanisms used by orchids in preparing his 1862 book on the subject, he rediscovered Sprengel, and expressed great admiration for his work. Since that time, Sprengel has been properly hailed as one of the founders of floral biology and floral ecology. Darwin’s own copy of Sprengel’s book survives at Down House and contains detailed manuscript notes in his own hand.

One man who did appreciate Sprengel’s work, long before Darwin, was James Edward Smith, the founder of London’s Linnean Society. In 1794, one year after Sprengel’s book appeared, he named a new plant from Australia, the pink swamp-heath, Sprengelia incarnata (fifth image).

There is no known portrait of Sprengel, and although we know he died in Berlin, his grave is unknown as well. But there is a small memorial stone in the Berlin Botanical Garden, with a plaque that is patterned after the border on the title page of his classic book (sixth image). Many of us would be happy to be commemorated with a marker as handsome as this one.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.