Scientist of the Day - Daniel Sennert

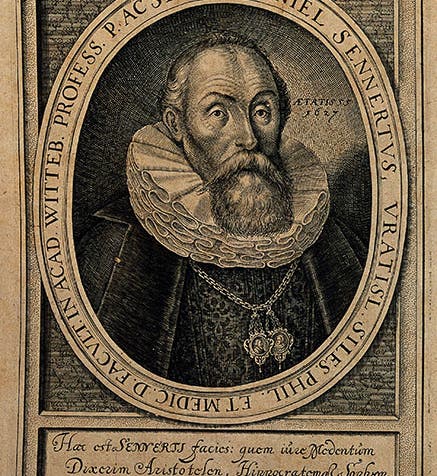

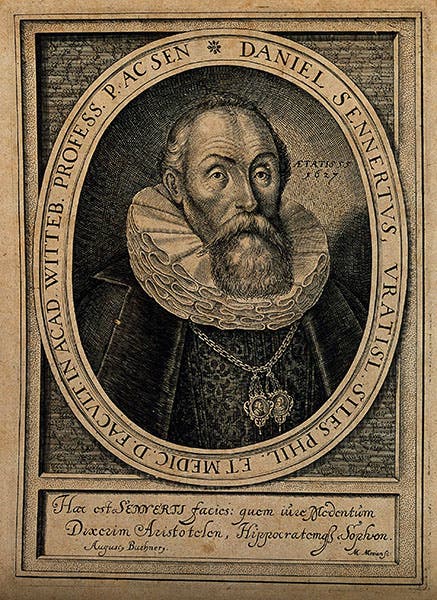

Daniel Sennert, a German physician and chemist, was born Nov. 25, 1572, in Breslau (now Wrocław, Poland). He studied at the University of Wittenberg and taught there for his entire career, dying in harness on July 21, 1637, at age 64.

Sennert was one of the first professors of medicine to make chemistry, or chymia, as it was then called, a vital part of the medical curriculum. Traditional Galenic medicine relied on botany for its pharmaceuticals, and the only chemistry involved was the distillation of plant products. The Swiss physician Paracelsus had been the first to bring alchemy into medicine and argue for the importance of metallic and mineral preparations in treating various diseases, such as syphilis. But Paracelsus was also a renegade, rejecting Galenic medicine entirely; furthermore, his “iatrochemistry”, or medical chemistry, had a considerable occult element, so that the physician was also a magus, manipulating celestial influences while treating a patient.

Sennert adopted iatrochemistry but stripped it of its magical, mystical components, and replaced it with laboratory-based chymia. He followed the lead here of Andreas Libavius, who was one of the first to do what looks like chemistry to us, although he retained the title Alchymia for his major book. But Libavius was not primarily a physician, unlike Sennert, who had more success in convincing the medical community of the relevance of chemistry for medical practice.

Sennert was also important in early modern science for an entirely different reason: he was an atomist, or corpuscularian, at a time when atomism was still unpopular. Aristotle had rejected the atomism of Democritus out of hand, because it maintained the existence of void space, and since natural philosophy was still primarily Aristotelian in the early 17th century, atomists were few and far between. Giordano Bruno was an atomist, but I am not sure that this was any help in rehabilitating Democritus.

Atomism began to make inroads with the work of French natural philosophers such as Marin Mersenne and Pierre Gassendi (and perhaps with the rising popularity of Cartesian philosophy, although René Descartes was not an atomist). Robert Boyle was the foremost corpuscularian of the last half of the 17th century; it used to be assumed that Boyle was influenced by the French physicists, and the importance of the chemical atomists, like Sennert, was discounted. However, in the past 25 years, Sennert scholars have discovered that Sennert had a profound influence on Boyle, an influence that Boyle did not publicly admit, and that perhaps the medical chemists had a more important role in the scientific revolution than they are given credit for.

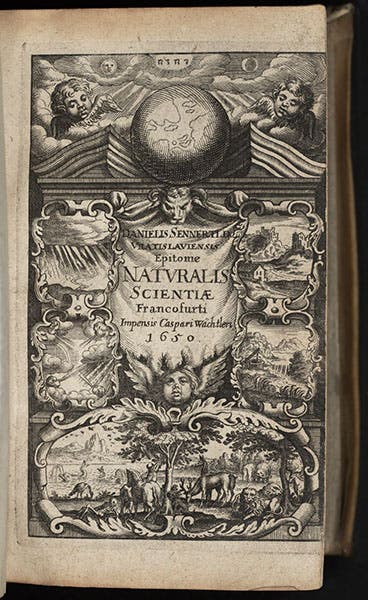

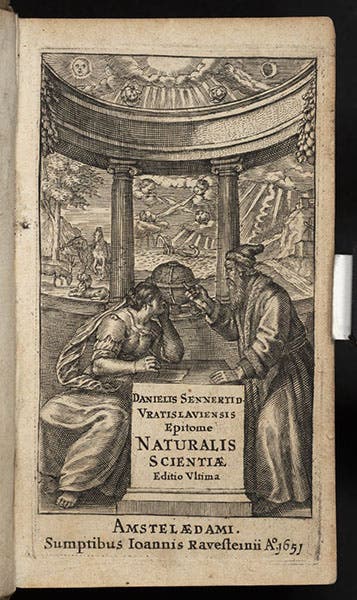

We have a contemporary set of the complete works of Sennert in our collections, three thick, unillustrated folios that I have hardly looked at, since they are primarily medical. But he also wrote, early on in his career, an Epitome of Natural Knowledge, which was very popular among students, and grew even more popular after his death. We have two editions of this, published in Frankfurt in 1650 and in Amsterdam in 1651. Both have illustrated title pages, and we thought we would show them here, since we have little else in the way of imagery for the occasion. Sennert would have had no hand in their iconography, since he had been dead for over a decade, but the meteorological theme in both of them is interesting, since Sennert was indeed partial to Aristotle's book on meteorology. The fuzzy Earth in the 1650 edition is also reminiscent of the "intellectual globe" of Francis Bacon. But that is the subject for another day. Or perhaps a book.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![Using an astrolabe to measure the depth of a well, woodcut in Elucidatio fabricae vsusq[ue] astrolabii, by Johannes Stöffler, 1513 (Linda Hall Library)](https://preview-assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/a998eb50-55d2-4a88-ace2-a50aa5fa86e7/Stoffler%201.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)