Scientist of the Day - Edward Collier

Edward Collier – Scientist of the Day

Edward Collier, a Dutch painter, was born Jan. 26, 1642, in Breda in the Netherlands. He studied in Haarlem, then moved to Amsterdam. He came to England around 1693, painted there until the early 1700s, returned to Holland go a few more years, then came back to London, where he died, and was buried on Sep. 8, 1708. In Holland, he is referred to as Evert, or sometimes Edwaert, Collier.

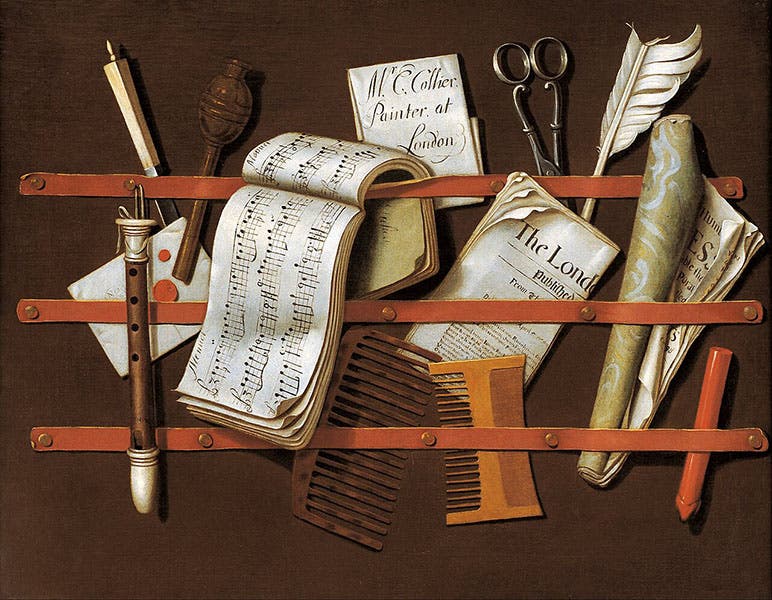

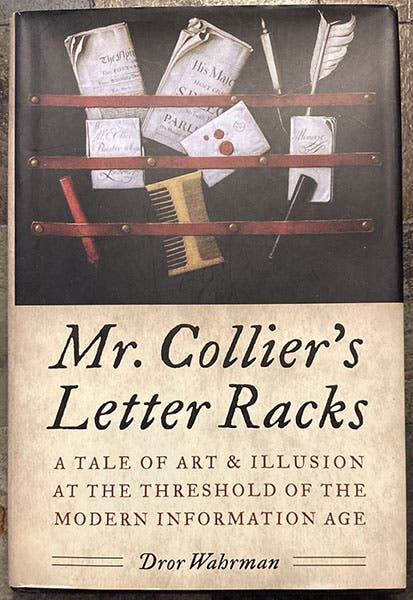

Collier painted still lifes almost exclusively, of two sorts: vanitas-themed paintings, and trompe-l'oeil paintings. We are going to discuss the latter, and their connection to early modern science, because of a book published some years ago that greatly intrigued me: Mr. Collier's Letter Racks (2012), by Dror Wahrman (third image).

Dust jacket, Mr. Collier’s Letter Racks, by Dror Wahrman, Oxford University Press, 2012 (author’s copy)

A trompe-l'oeil painting is one that fools your eye, usually by including something in the painting that appears to be outside the painting, such as a fly or a flower petal. They originated in the mid-17th century, probably because they pleased patrons, especially monarchs, who liked trying to brush non-existent flies from their works of art. They were especially popular in the Netherlands, where still-life painting was a dominant genre, and in England, which imported much of its artistic sensibilities from the Dutch.

It has been long noticed that the countries that admired still-life painting, primarily Holland and England, were also the locales where experimental science arose, based on close observation of nature, so the fact that the microscope maker Antoni van Leeuwenhoek and Johannes Vermeer shared the town of Delft is not seen as a coincidence but rather a convergence of thought on how one should go about viewing nature.

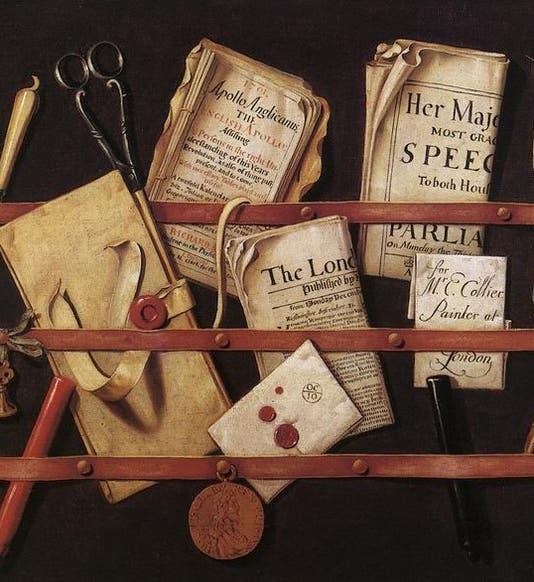

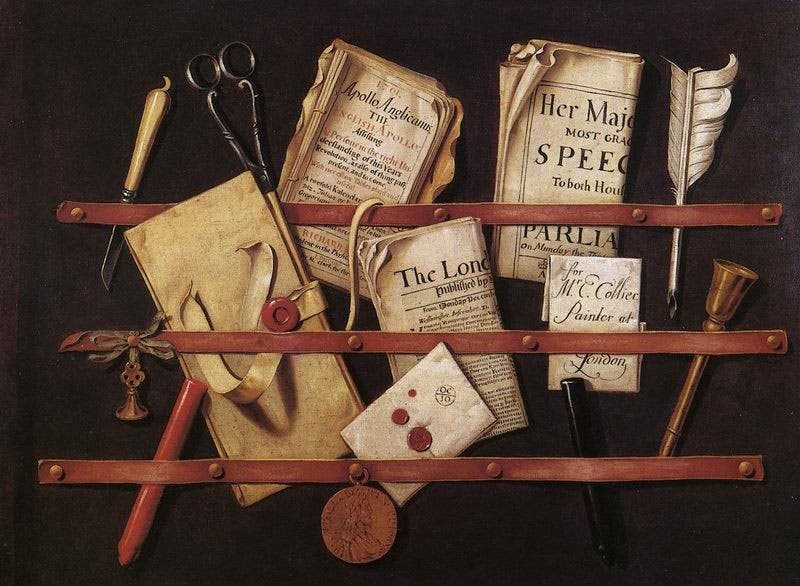

Trompe- d'oeil paintings attempt to throw a monkey wrench into the works, by showing that what you perceive is not necessarily what is there. Collier painted letter racks, consisting of 2 or 3 leather bands loosely nailed to a wooden board, with a variety of ephemera inserted behind the straps - almanacs, Royal speeches to Parliament, letters, pen knives, magnifying glasses, combs, quills, sticks of sealing wax, and medallions. Only none of it was real; everything – board, straps, letters – was painted on a piece of canvas.

Well, that is fun, but no one realized that Collier was up to deeper mischief until Wahrman took a closer look at Collier's letter racks, mostly ones painted in London just before or after the turn of the century. This was a revolutionary time in England, when the Stuart king James II had been removed and replaced by William of Orange, and not everyone was happy about this. Collier seems to have been a secret Jacobite – a supporter of the deposed James II – and, by his selection of speeches and almanac issues (which are different in every painting), he was able to make political points, without anyone realizing it. One painting even has two documents, visibly dated 1701 and 1702, in which, because of calendar differences, and the fact that Holland started the New Year on Jan. 1 and England on Mar. 21, the 1702 document actually predates the one from 1701 - an illusion in time.

It is probably not a coincidence that fellows of the Royal Society were concerned with the same kinds of issues – can the eye and the senses be trusted? When you see something through a microscope, is it really there? Are the spots on Mars real blemishes, or artifacts introduced by the telescope or the eye?

Collier's paintings seem to say: you are wise to be wary of what your eyes tell you. And the ultimate joke, which Wahrman does not reveal until the final pages of his book, is that there is no evidence that anyone in England or Holland actually had letter racks like this in 1700. Collier not only filled his letter racks with illusionary ephemera, his letter racks, as objects, are illusions as well. What is real, indeed.

I have never seen a Collier letter rack in person, but there are quite a few in the United States, and I intend to seek one out in the near future, perhaps the one at the Art Institute in Chicago. If your museum has one, be sure to look it up in Wahrman's book to find out what secrets it is hiding.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.