Scientist of the Day - Euclid of Alexandria

Euclid of Alexandria, a Greek mathematician, lived around 300 BCE. We know next to nothing about the man, except what we can glean from his principal surviving work, the Elements [of Geometry], one of the most influential books ever written. There were many great geometers before Euclid – Pythagoras and Eudoxus spring to mind – but Euclid made them all instantly obsolete with his Elements. He arranged his book in such a manner, beginning with definitions; specifying the axioms that must be assumed because they cannot be proved, and then proceeding to the things that can be proved, the theorems, 13 books of them. This Euclidean method, as it came to be called, was a stunner, because you cannot have opinions about a Euclidean proof – either you find a flaw (which you will not do) or you accept the proposition as proved. The only thing you can argue about is the fifth axiom, the so-called parallel postulate, which seems like it ought to be provable, but it turns out you need it.

Every culture that discovers Euclid is impressed by the inevitability of the Elements. Certainly, the Arabs were, translating the Elements into Arabic from the original Greek, often via Persian. In the High Middle Ages in Europe, Euclid was rendered into Latin, from the Arabic, since Greek manuscripts were no longer to be found. There were many errors, interpolations, and later emendations in these thrice-translated texts, but that really didn’t take anything away from the power of the Euclidean method.

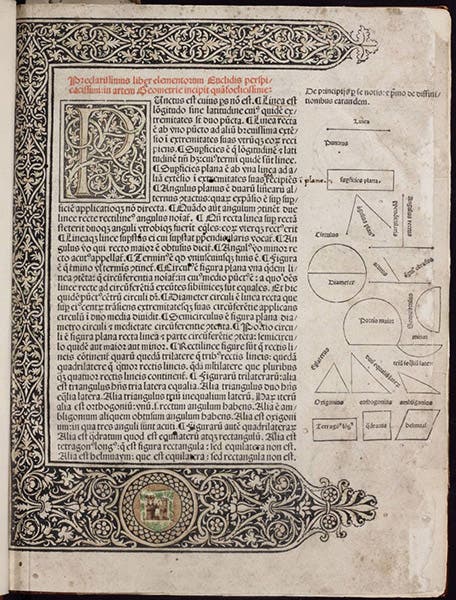

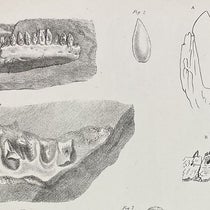

The first printing of Euclid’s Elements, the editio princeps, came in 1482, when Erhard Ratdolt published the Latin translation of Campanus from Arabic. This is a famous edition in the history of printing, the first book to have diagrams to illustrate the text. We show the first page, and the page containing the last proposition of Book 1, the Pythagorean theorem, because its diagram is so recognizable, with the big square on the hypotenuse and the smaller squares on the other two sides (third image).

We have scores of editions of the Elements in our history of science collection. I thought about trying to count them, but gave up, since it is hard to draw the line between an edition of the Elements and a book that just uses or comments upon it. Instead, we simply show a page each from some of our significant or visually striking editions. The first English edition, by Henry Billingsley, published in 1570, is noted for the preface by John Dee, and for the 3-D pop-up diagrams in the later books (fourth image).

The Typographia Medicea in Rome commissioned a special set of Arabic fonts and proceeded to publish an Arabic Euclid in 1594; our copy is unbound, and we show the page with the Pythagorean theorem (fifth image).

An edition of all of Euclid’s surviving works, including the Elements, edited by David Gegoy in 1703, is noteworthy for its engraved frontispiece (sixth image), which we discussed in more detail in a post on Gregory.

Certainly, the most visually appealing edition of Euclid in our collections is that of Oliver Byrne (1847), where primary colors were used instead of letters in many of the proofs (seventh image). We wrote a post on Byrne once, with additional views of the colored diagrams, and also containing an original clerihew illustrated by our designer at the time, Melissa Dehner.

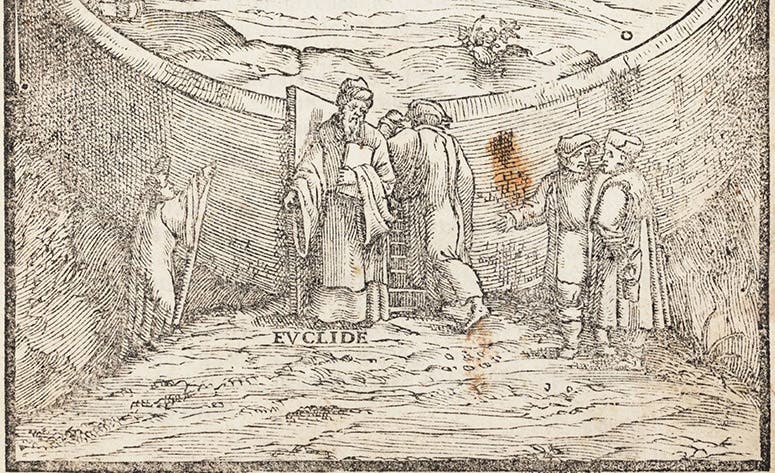

We have no idea what Euclid looked like, but there have been many attempts to portray him nevertheless. We like the image on the frontispiece to Niccolò Tartaglia's Nova Scientia (1537), where Euclid is guarding the gate to Plato's Academy, enforcing the Platonic precept, "Do not enter here if you do not know geometry" (first image).

The only statue of Euclid of which I am aware is in the Oxford Museum of Natural History, a museum well worth visiting, not only for its abundant statuary, but for its rich contents and its architecture (last image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu