Scientist of the Day - Francis Orpen Morris

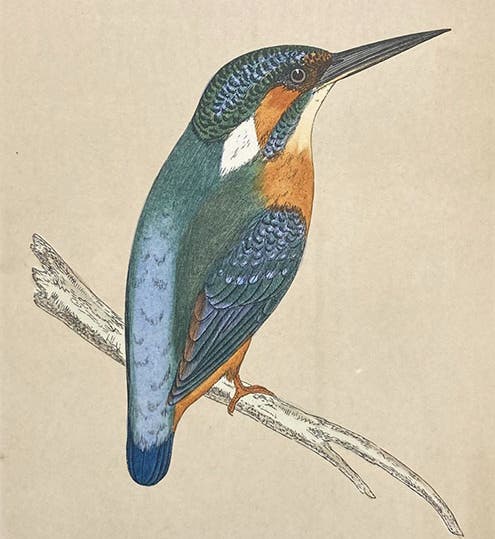

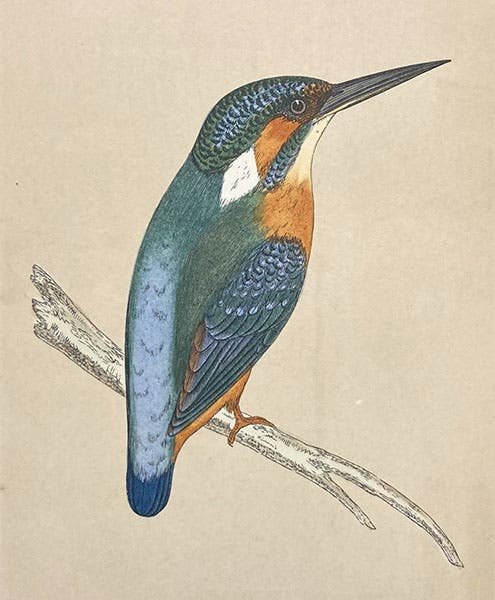

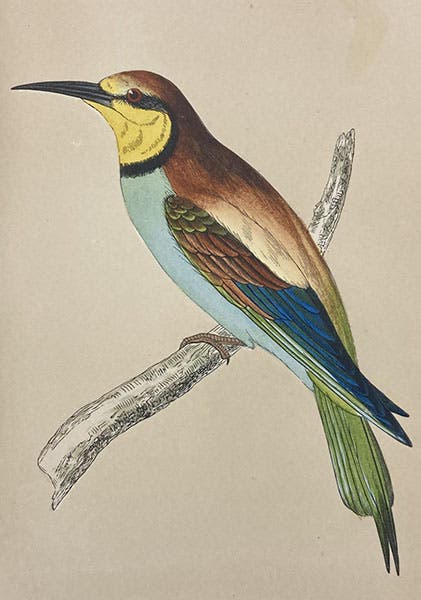

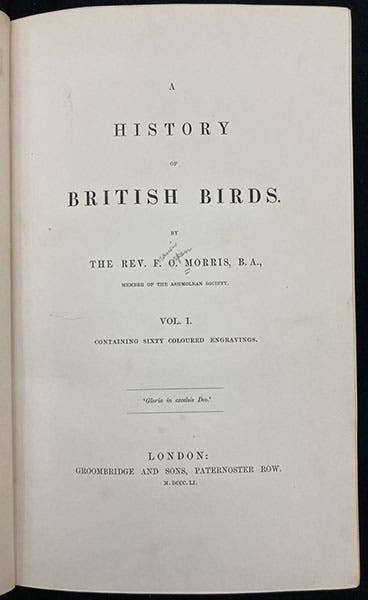

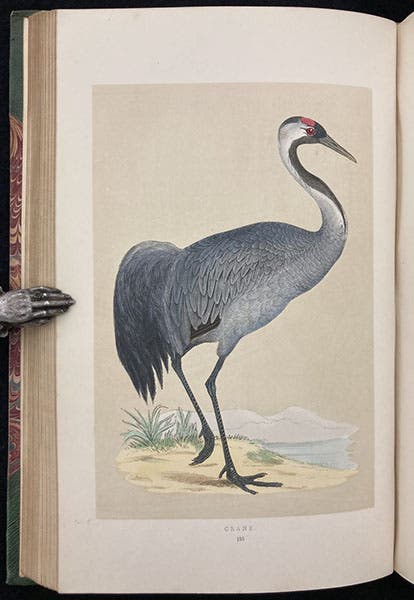

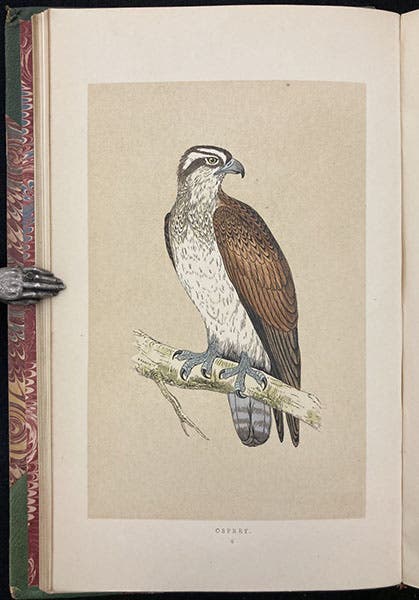

Francis Orpen Morris, a British naturalist and clergyman, died Feb. 10, 1893, at age 82. Morris was born in western Ireland, grew up in Dorsetshire, attended Worcester College, Oxford, and in 1834, entered into the life of an Anglican curate, holding that position in Cheshire, Nottinghamshire, and North and South Yorkshire, before settling down in the tiny hamlet of Nunburnholme in East Yorkshire, where he happily spent his last 40 years, not so much saving souls as writing books about birds, insects, and antiquities. All I know about Morris has been gleaned from one article (see below) and the one work of his that we have in our collections, A History of British Birds, published in 6 quarto volumes between 1851 and 1866. It sits in our vault on the same shelf as John James Audubon's The Birds of America (1840-44) in its quarto format, and it yields not an inch to its more illustrious neighbor. All of the images included here are from Morris's British Birds, and, as you can see, they are lovely indeed.

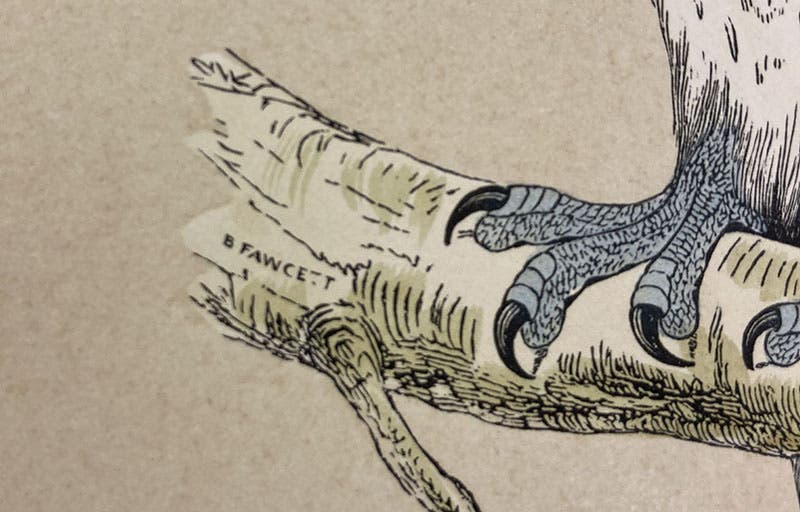

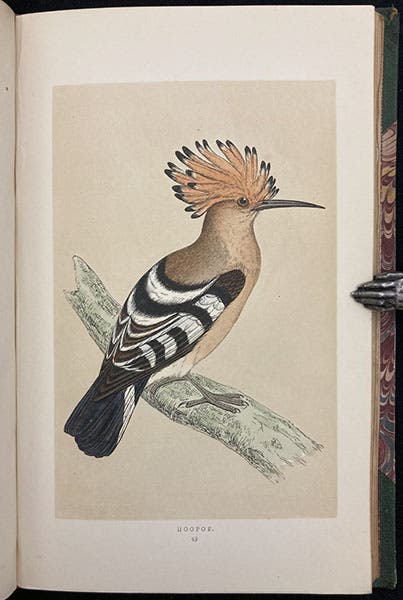

Morris was not tesponsible for the illustrations – those were provided by Benjamin Fawcett. No one to my knowledge has written about these images, but they appear to be hand-colored wood engravings – that was Fawcett's specialty – with some of the color possibly added by additional woodblocks, a process known as chromoxylography, a medium analogous to chromolithography, which was also becoming popular in the 1850s. I cannot really tell how all the color was applied, although I am fairly certain that much of it was hand-painted. I have provided several details, of the crane and the hoopee and the kingfisher. The close-up views also reveal the great amount of detailed fine-line work that can be crammed into a wood engraving, as Thomas Bewick had demonstrated a half-century earlier.

Most of the illustrations in Morris's volumes are not signed. However, some are, such as the osprey that appears early in volume 1, from which I show a detail of the branch with Fawcett's name (seventh image).

Morris cannot take credit for the illustrations that are the glory of his book, but he did write the text, and there was a lot of text. He had seen and collected (i.e., shot) most of the birds he described, and he knew their haunts and habitats well. His descriptions perhaps fell short of those of Gilbert White, but Morris had a puckish sense of humor that often shows through, as in his description of the hoopee (eighth and ninth images):

The figure before us is colored from a specimen in my own collection, which was shot some years ago on the southwestern border of Dorsetshire ... occasionally, it has been known to breed here, and doubtless would oftener do so, were it not incontinently pursued to the death at its first appearance (pp. 316-7, vol. 1).

In other aspects of his life, Morris was far less likeable. He was passionately opposed to fox-hunting, and to vivisection, which sounds like a good thing to some of us, but he devoted equal passion to anti-feminism, and, after 1859, to opposing Darwinian evolution, and he hated Thomas H. Huxley with a passion, who was doubly an evolutionist and an animal experimenter. Morris was, in short, a zealot, and in the one portrait that survives, he looks like a zealot. It is such an unpleasant portrait that I prefer not to include it here, with all these beautiful birds. You can find it on Wikipedia, if you must search it out.

The only in-depth article on Morris that I could find appeared in the ornithological journal The Auk in 1938, and was written by Charles Kofoid, who recounted many of Morris's odd crusades in delicious detail and who described Morris as a “versatile, irascible, dogmatic, and persistent critic and naturalist.” You can read the article here. Kofoid was an ardent naturalist himself, although he preferred the kind of living thing you could bring up in a dredging net from the ocean floor. Kofoid was the former owner of our first edition of Conrad Gessner's Historia animalium (1551), which contains his delightful bookplate, which you can see in our post on Kofoid. Small world, as it often is in the rare book business.

Perhaps one day, we will find out more about the wood engraver, Benjamin Fawcett, and then we can write a post about Morris's British Birds, without Morris.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.