Scientist of the Day - Gideon Mantell

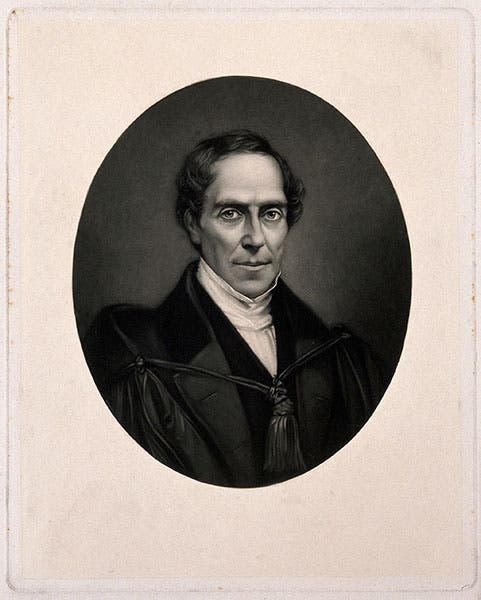

Gideon Algernon Mantell, an English surgeon, fossil hunter, and geologist, died Nov. 10, 1852, at age 62. Mantell is best known for discovering the remains, initially teeth, then more substantial skeletons, of Iguanodon, a Cretaceous herbivorous dinosaur, which he described in 1825. Iguanodon and William Buckland's Megalosaurus, announced the year before, are the first two dinosaurs discovered, and were given the name dinosaur by Richard Owen in 1842. We have written a post on Mantell and Iguanodon.

Mantell had a difficult life, although he was one of England's most knowledgeable authorities on Mesozoic fossils and the geology of southeast England. Charles Lyell, 7 years younger, had immense respect for Mantell. Mantell originally practiced medicine in his home town of Lewes in Sussex. But when he relocated to Brighton in 1833, his obstetric practice suffered, especially since he was often away, investigating new fossil sources. He built up a large museum in his home, but he never made any money off it. In increasing financial difficulty, he had to sell his fossil collection to the British Museum, a long, drawn-out process that caused him considerable stress. In 1839, his wife Mary Ann, his collaborator and illustrator, left him; his son Walter emigrated to New Zealand (they would never see each other again), and in 1840, his beloved teen-age daughter, an invalid with tuberculosis infecting her hip, died, at age 18.

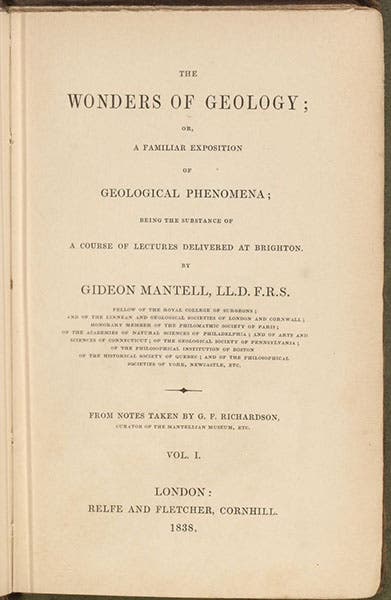

Mantell got through this difficult decade by giving a series of lectures in Brighton on the geology of England in 1837, which he then published in 1838 as The Wonders of Geology, a two-volume work with 6 colored plates, a mezzotint, and 39 text wood engravings. It was unquestionably Mantell's most successful literary effort, the first edition selling out immediately, calling for a second printing in 1838, a third edition in 1839, and a fourth in 1840. It was the best-selling geology book of its time, aimed at a more general audience than Lyell's Principles of Geology (1830-33 and many later editions), and successfully finding that audience.

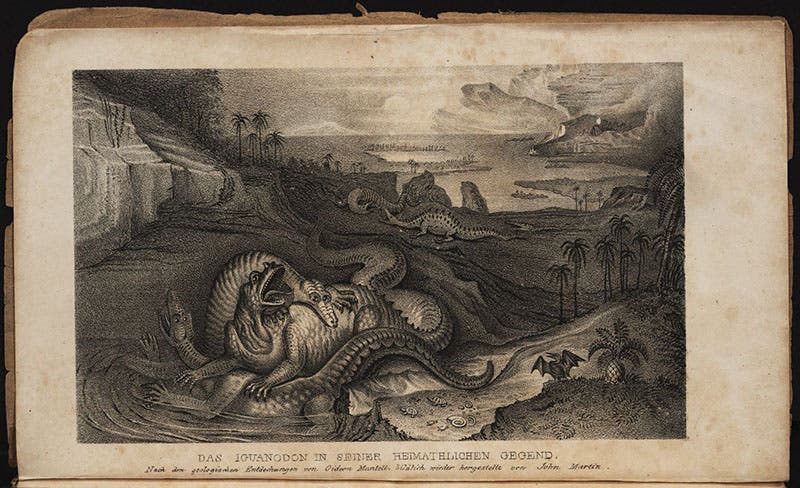

We have the first edition in our collections, and the fourth of 1840, as well as a German translation of 1839, still in its original wrappers. We show here three of the hand-colored engravings from the 1838 edition, plus the frontispiece and one of the wood engravings, and also the frontispiece from the 1839 German edition, since it is in some ways an improvement on the original.

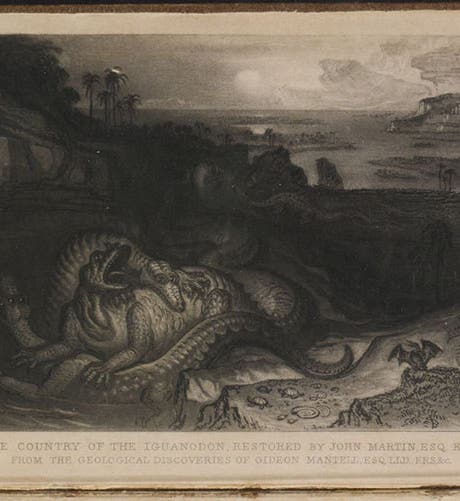

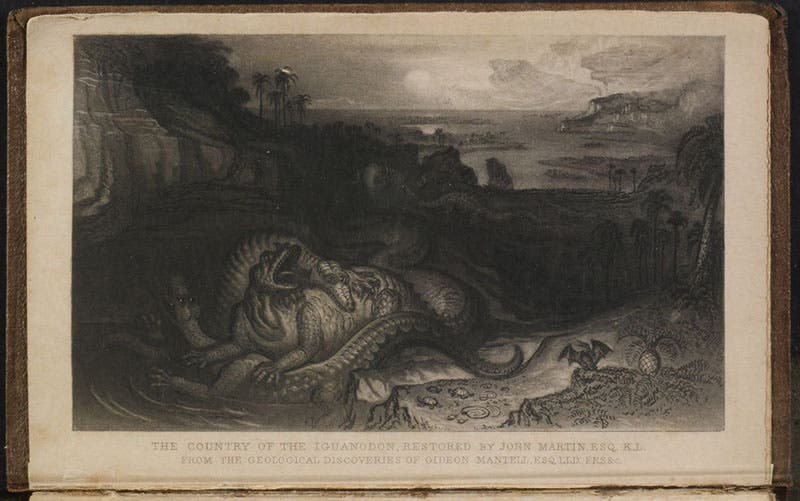

The frontispiece (first image) gets top billing here, because it really is eye-popping, a mezzotint by John Martin called "Country of the Iguanodon,” showing a Megalosaurus wrestling with an Iguanodon, while various other prehistoric beasts writhe about in a primordial fen. The larger version used for the lectures must have been spectacular. Because mezzotints are, by their nature, very black, much of the detail gets lost, so we also include, at the end of our essay, the copy of Martin's mezzotint in the 1839 German edition of Wonders, which is an ordinary lithograph, with details more easily seen.

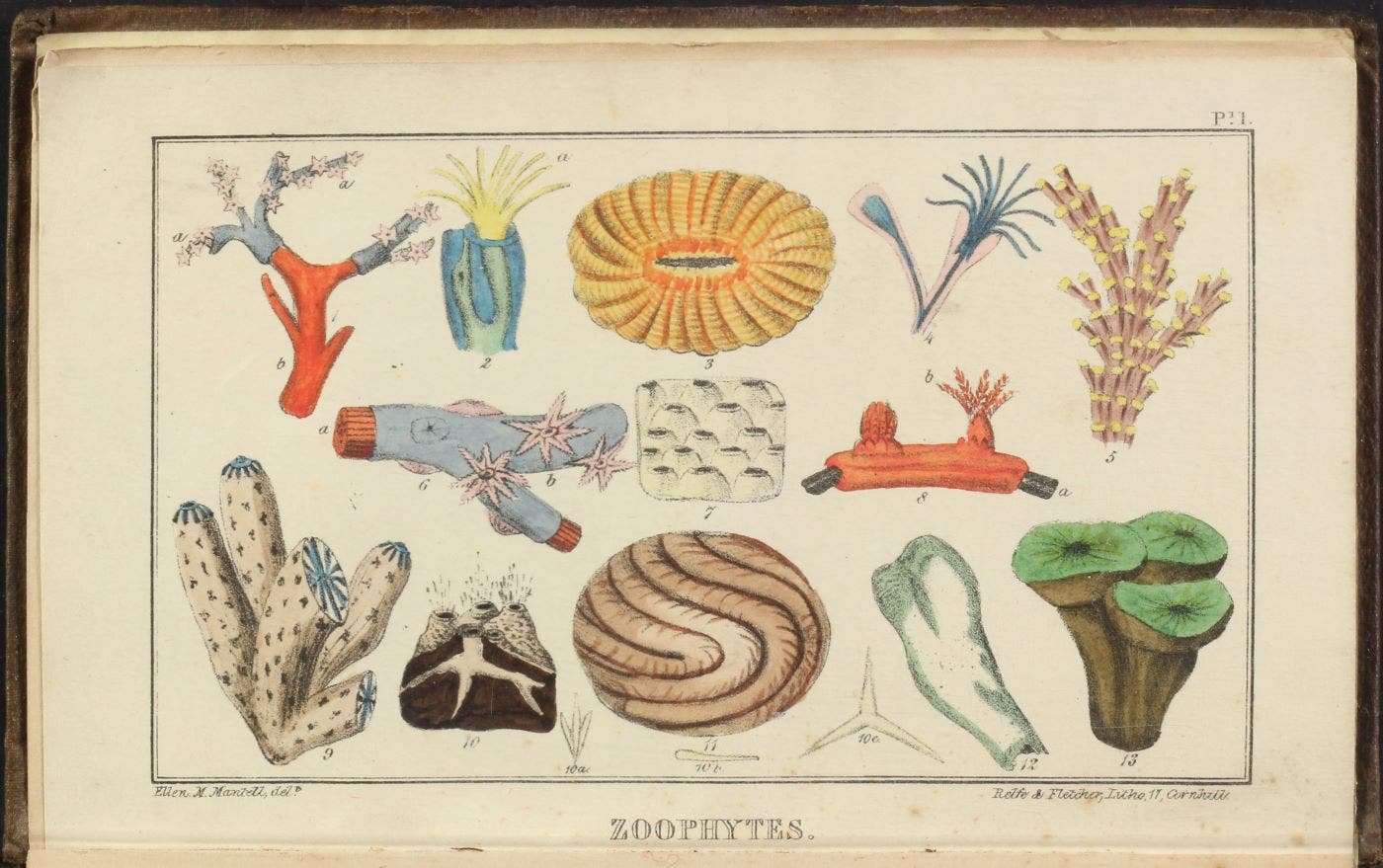

The frontispiece for volume 2 (fourth image) is a hand-colored lithograph of various corals, which Mantell calls Zoophytes, or plant-animals. This was drawn by his oldest daughter, Ellen Maria. It is quite vivid, especially in its coloring, and does just what a frontispiece is supposed to do, draws the viewer into the book itself.

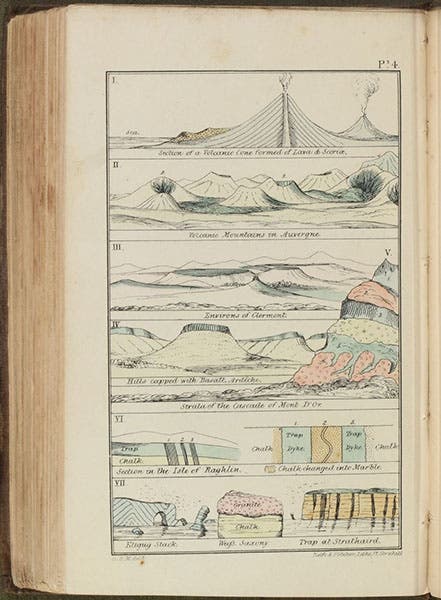

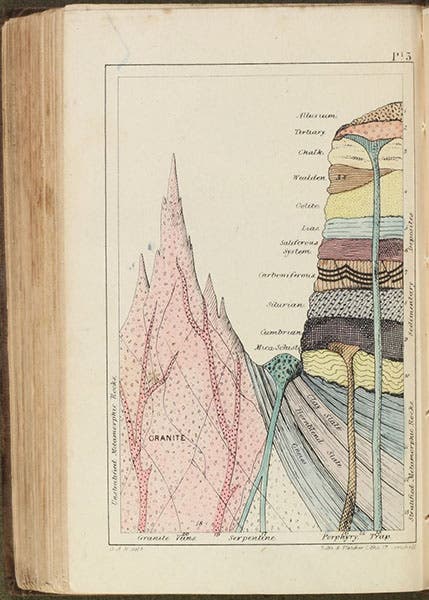

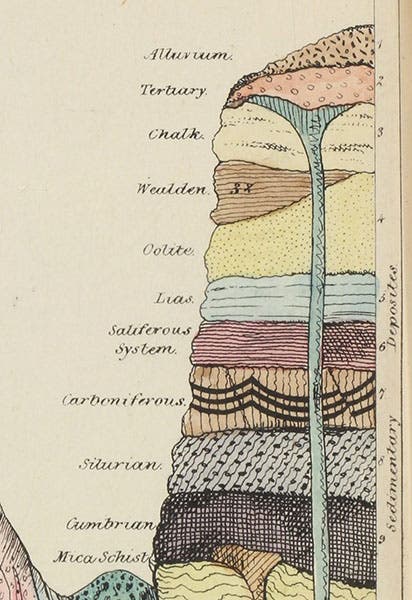

My favorite plate is tucked into the back of volume 2: an idealized section of the Earth's crust, showing igneous, metamorphic, and sedimentary rocks and their relationship to one another (sixth image, just above). Idealized sections in geology books of this time are most uncommon, especially ones that show the various strata as real rock formations. In fact, it is the only one I know. I used to show it regularly to my classes when I discussed 19th-century geology, so students could see how the "Oolite" related to the "Lias" and the "Chalk," and where one might find a trap-dike. As a bonus, it is beautifully colored. Gideon himself drew this for the lithographer. We also include a detail of the sedimentary strata (seventh image, just below).

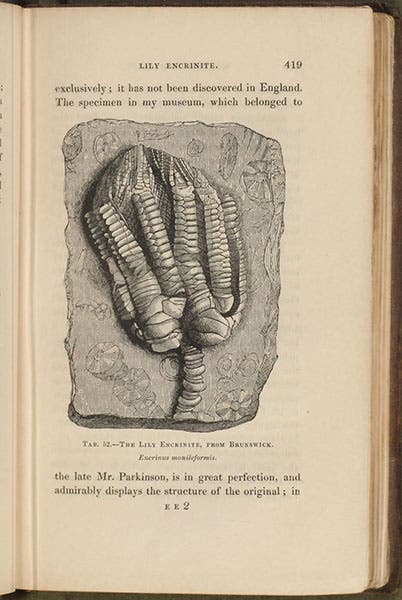

Most of the wood engravings embedded in the text are fine and show simple geological sections and ammonites and the like. But one of them, nearly full-page, shows a "lily encrinite," some kind of crinoid; it is beautifully cut, and I had to include it here (eighth image, just below).

The 1840s were not much kinder to Mantell than the 1830s, even though his books sold well and his reputation was firmly established. He entered into regular correspondence with Benjamin Silliman at Yale, which lasted right up until Mantell's death; Silliman seems to have had great respect for Mantell. But Mantell ran afoul of Richard Owen because of some mild criticism of an Owen interpretation, and Owen proceeded to make snarky comments about Mantell whenever he could for the rest of Mantell’s life. Indeed, upon Mantell's death, Owen wrote an anonymous obituary in which he further belittled Mantell's accomplishments, an act that enraged many of his colleagues.

But Mantell had more serious problems than Owen. He suffered a carriage accident that caused or exacerbated a spinal defect, now known to be scoliosis, which left him in constant pain, and he had great difficulty getting about. He took opiates for the pain. Finally, on this day in 1852, unable to get out of bed, and perhaps with an overdose of opiates, he passed away.

Mantell was buried in West Norwood Cemetery in London, under a small monument modeled after an Egyptian temple, for reasons unknown to me.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.