Scientist of the Day - Giovanni Alfonso Borelli

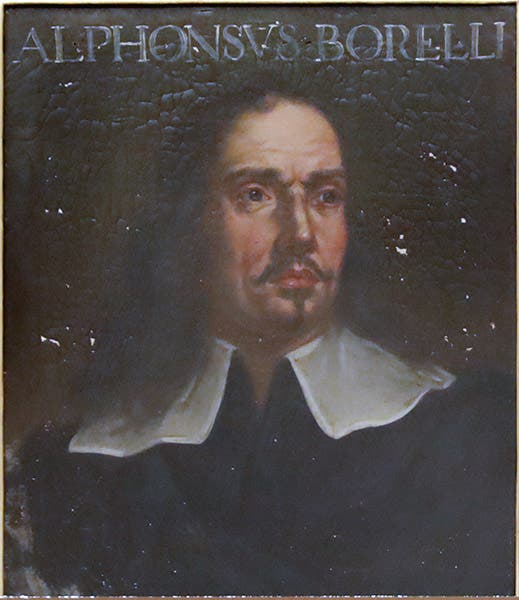

Giovanni Alfonso Borelli, an Italian physicist and astronomer, was born Jan. 28, 1608, in Naples. He studied in Rome under Benedetto Castelli, an early supporter of Galileo Galilei, who had taught at Pisa and was now (as of 1626) a professor of mathematics at the Sapienza in Rome. Borelli may have spent some time with Tommaso Campanella during the years he was free from prison in Rome in the late 1620s. Borelli applied for the vacant chair at Pisa in 1640, trying to follow in the footsteps of both Galileo and Castelli, with Castelli’s enthusiastic recommendation. When that failed, Borelli went to Messina in Sicily, where he was professor of natural philosophy and mathematics from 1640 to 1656. In 1656, he was finally successful in obtaining the Pisa position, and he arrived in Florence just about the time that Leopoldo de’ Medici was establishing the Accademia del Cimento in Florence, one of the first scientific academies. Borelli was one of the founding members of the Academy, which also included Francesco Redi and Lorenzo Magalotti. Interestingly, when Borelli returned to Messina in 1667, the Cimento Academy folded up shop.

Borelli worked in many fields, including not only astronomy and physics, but also physiology, anatomy, biomechanics (a field that he founded), and he even dabbled, on one occasion, in geology. We have half-a-dozen first editions by Borelli in our History of Science Collections.

We are going to focus today on Borelli’s study of the moons of Jupiter. The book was called Theories of the Medicean Planets, using Galileo's name for the four satellites of Jupiter that Galileo discovered back in 1610 and announced in his Sidereus nuncius (1610). But the title of Borelli’s book went on: ... Deduced from Physical Causes, which means that Borelli was hoping to explain how and why the moons of Jupiter move the way they do. Johannes Kepler had been the first to look for causes in planetary motions (which made him the founder of celestial dynamics), and Borelli, fifty years later, was really the first to travel on the pathway the Kepler laid out.

Borelli concluded that the orbits of Jupiter’s moons were the result of the combination of their tendency to fall into Jupiter because of gravity, their inclination to fly outward, like a ball being whirled on a string, and a force that moved them around Jupiter, analogous to the force that Kepler saw emanating from the Sun like spokes on a wheel and moving the planets around in their orbits. The net result was an elliptical orbit for each of Jupiter’s moons.

Borelli, however, failed to realize that the period of an orbiting body is related to the radius of its orbit by a simple law. We call it the period law, or Kepler's Third Law, because Kepler first announced it back in 1619, in his Harmonies of the World. But no one else understood Kepler’s period law in 1666, so Borelli was not alone. It would take another genius, Isaac Newton, to appreciate what Kepler had done, and to use the period law to discover his own law of universal gravitation. Newton did praise Borelli’s book highly in the Principia.

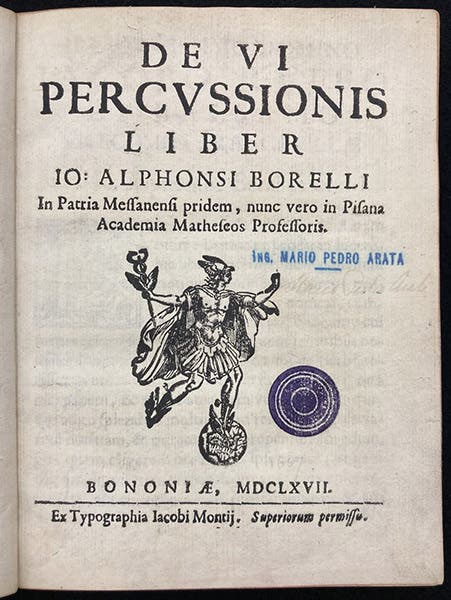

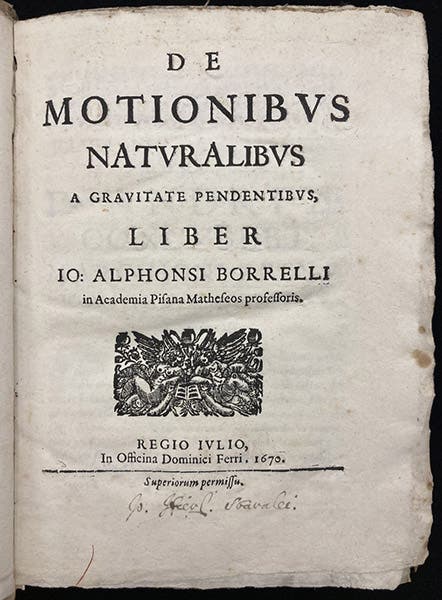

Borelli’s book on the Medicean moons has only some line diagrams at the end, which are not too appealing to the general reader, so we show instead the title pages of the next two books Borelli published, on the force of percussion (third image), and on falling bodies (fourth image). His best-known book, De Motu Animalium (On the Movement of Animals), which was a study of biomechanics, was published in two volumes just after Borelli’s death in 1679. It has a handsome engraved title page, and we will look at this publication in a subsequent post.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.