Scientist of the Day - Giovanni Battista della Porta

Giovanni Battista (Giambattista) della Porta, a Neapolitan natural magician, died Feb. 4, 1615, at the age of 75. Natural magic in the 16th century was the study of cause and effect in the world around us, a world in which causes were numerous and just about anything could happen. The domain of natural magic included alchemy, astrology, botany, magnetism, optics, medicine, physiognomy, numerology, and magic squares, to name just a few.

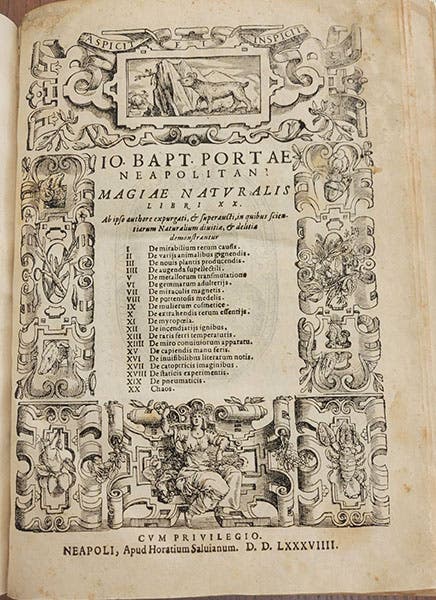

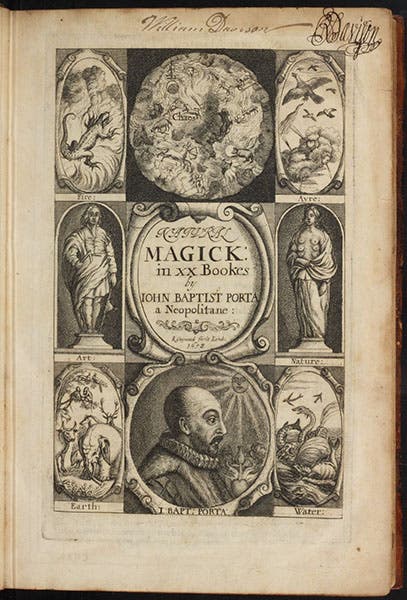

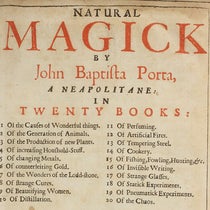

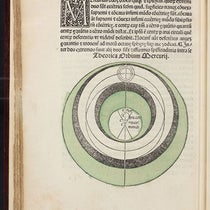

There were several influential treatises on natural magic published in the first half of the 16th century, by the likes of Cornelius Agrippa, but they were eventually eclipsed by the Magiae naturalis of della Porta, published in Naples in 1589 (an edition of 1558 is often cited, but I have never seen a copy and am not sure it really exists). We have two copies of the 1589 edition, but copy one is much brighter than the second, and our images, such as the woodcut title page, come from that.

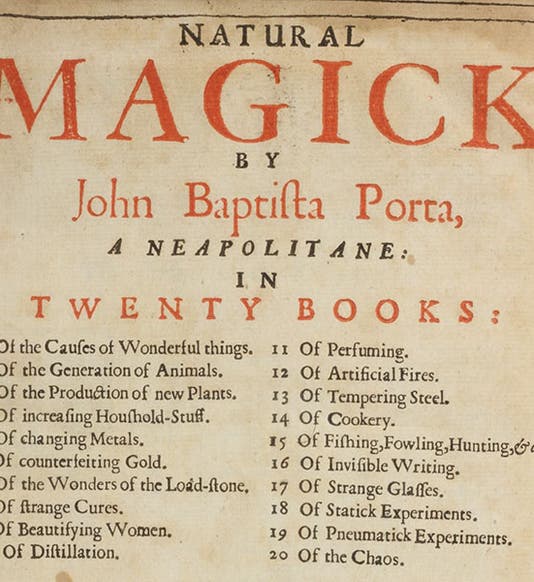

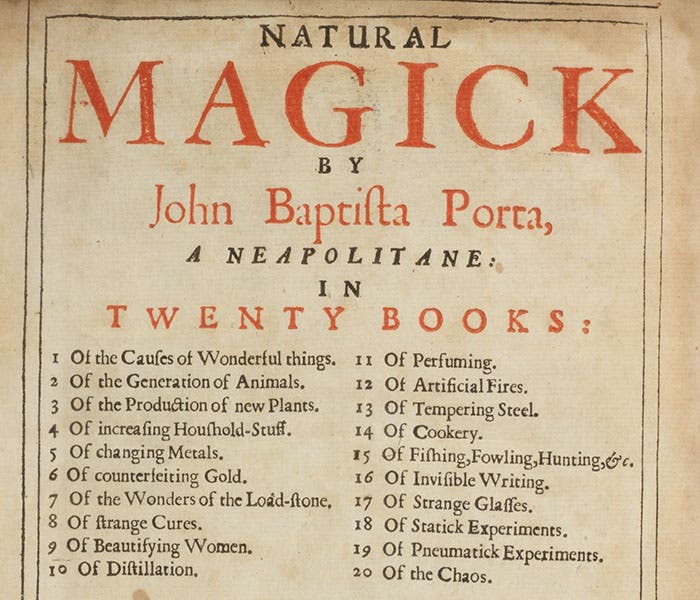

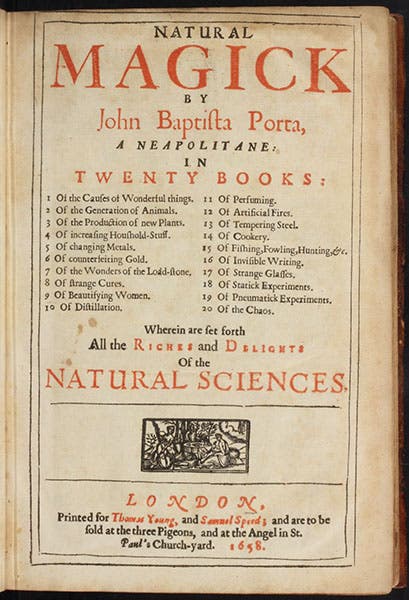

One of the interesting typographic features of Porta's book is that the Table of Contents is provided right on the title page, which is very unusual. So we see that Porta includes chapters on “increasing household stuff,” the lodestone, and “beautifying women,” and proceeds through distillation, invisible writing and ciphers (Porta is well known in the history of cryptography), and pneumatics. But my favorite chapter by far is Book 20, "Chaos," where he sticks everything that doesn't fit into one of the 19 more conventional chapters. Having a Chaos chapter should be a requirement for most books.

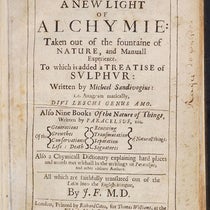

We are going to introduce at this point a book you have already been looking at, an English translation of Magiae naturalis that was published in 1658, when alchemy and magic were making a bit of a comeback in England. It has a compartmentalized engraved title page (fourth image), and a letterpress title page/table of contents that is a translation of the 1589 original, with the advantage that, if you read English, you can comprehend it (first and fifth images). Best of all, you will now be able to read an account of the quintessential natural magic demonstration, the use of a weapon salve.

The basic principle of natural magic is the concept of sympathies. Things that are in sympathy, because they have a common origin or appearance, can affect each other, even if widely separated in space. The seven planets correspond to the seven metals, so if you are trying to locate a supply of tin, Jupiter should be in a favorable astrological sign, so that it can have a positive sympathetic effect. A liverwort is telling us, by its appearance, that it has a sympathy with the liver and should be useful in pharmaceutical preparations.

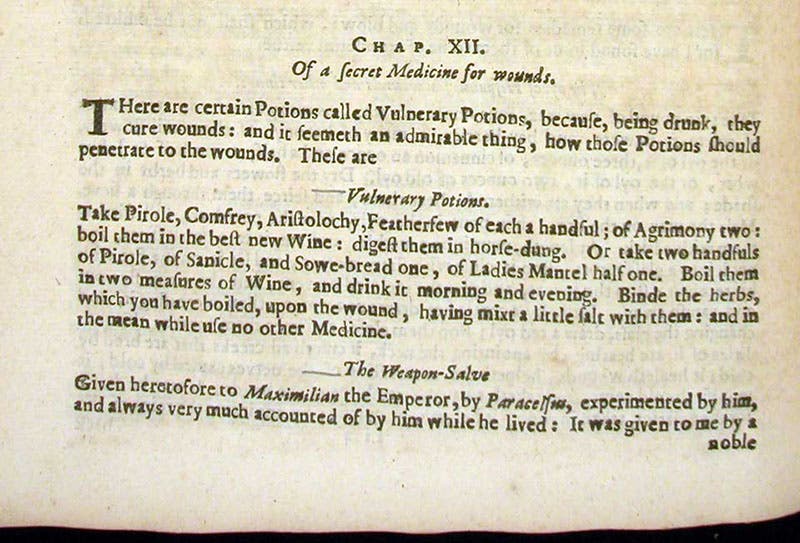

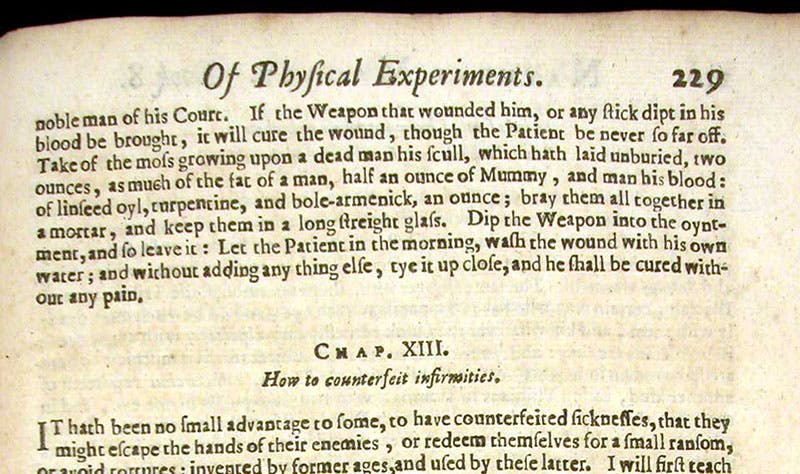

That being said, what two things could have a tighter bond than a wound and the weapon that made the wound. So if you want to treat a wound and not expose the patient to even greater harm, the wisest course, Porta tells us (following Paracelsus) is to apply a salve to the weapon, and allow the wound to heal by sympathy.

In the 1658 translation, the description and recipe for the weapon salve begins on the bottom of one page and continues on the top of the next, so we have to show it in two parts (sixth and seventh images). In point of fact, you were much more likely to recover from a battle wound if your surgeon applied a weapon salve to the weapon, than if he cauterized your wound with boiling oil, the most widely used alternative.

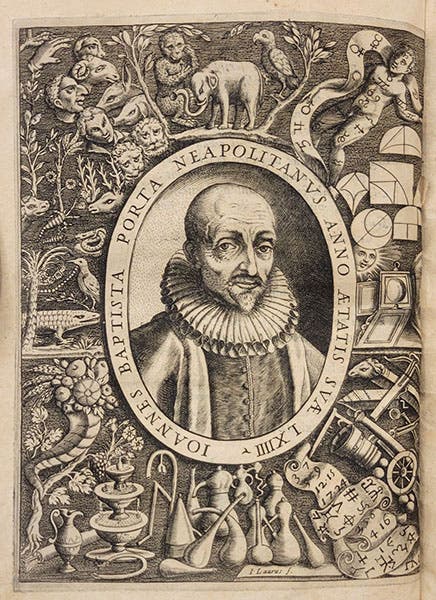

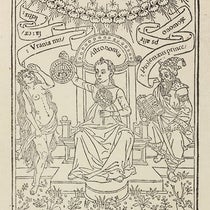

Quite a few years ago, in our first post on Porta, we discussed his most delightful book, On Human Physiogomy (1586), in which he published engraved portraits of a variety of human faces, and the animals they resembled, and discussed what their characters must have been like, since resemblance is a powerful causative force in the world of natural magic. That book had an engraved portrait, which we showed in our first post. The first edition of Magiae naturalis has only a woodcut portrait, and it was impressed on the back of the title page, with considerable show-through. So for our portrait today, we use the engraving that was included in another Porta book, De distillatione (1608; second image). There is also a small engraved portrait on the title page of the 1658 translation (fourth and eighth images).

There is more to be said about Porta; his work on optics has been acclaimed; he has been put forward as an inventor of the telescope; and he was invited to join the Academy of the Lynx in 1610, the scientific “club” in Rome that included Galileo. But that must await another day.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.