Scientist of the Day - Giovanni Domenico Cassini

Giovanni Domenico Cassini, an Italian/French astronomer, had a distinguished career in Bologna, where he built a large meridian in the church of San Petronio, and discovered the Great Red Spot on the surface of the planet Jupiter and a division in the rings of Saturn (Cassini's division; see our second post on Cassini). But in 1669, he was invited to Paris to take charge of building the Paris Observatory, and from that point onward, he was a French astronomer, Jean Dominique Cassini, and he began a dynasty of astronomers named Cassini that lasted a century and a quarter (see our posts on Cassini II and Cassini III).

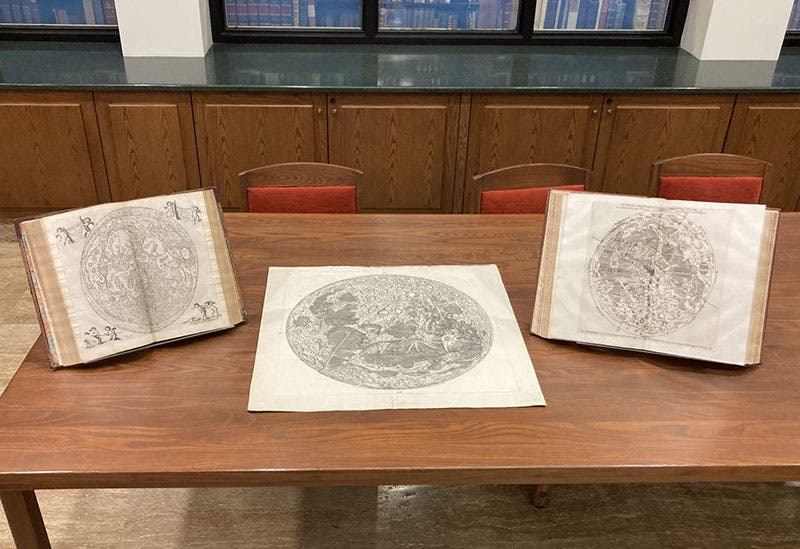

Today we are going to talk about and show you Cassini's great moon map, which he presented to the French Academy of Sciences on this day, Feb. 18, 1679, a map that we acquired by a generous gift just last year, a map that I thought we would never add to our collections (second and third images).

Creating lunar maps was a popular activity in the 17th century, when the invention and improvement of the telescope made such activities possible. Galileo made the first drawings of the lunar surface, although they were not really maps. But by the time of Johannes Hevelius, Claude Mellan, Giambattista Riccioli and Francesco Grimaldi, and Michael van Langren, in the period between 1645-1651, astronomers were being offered large engraved lunar maps with nomenclatures for their consideration. Many versions were made, usually espousing the nomenclature of Riccioli or Hevelius, but the maps, curiously, stayed the same size, about 11 inches across, so they would fit, folded in half, into a large quarto volume. Very few of these maps, except for the originals of Hevelius, Riccioli/Grimaldi, and Van Langen, were based on new observations.

Cassini began planning to issue a new lunar map also as soon as he got to Paris, certainly by 1671. He was a good observer but not much of a draftsman, so he roped the court artist, Jean Patigny, into making drawings for him. They made drawings for years, mostly of craters and maria near the terminator, where contrast is greater and shadows longer, and during eclipses. We don't know how many drawings Patigny made, drawings from which the map was compiled, but 57 of them still survive at the Paris Observatory today, so he probably made hundreds. I have never seen any of these drawings reproduced, nor have I found out anything about Patigny.

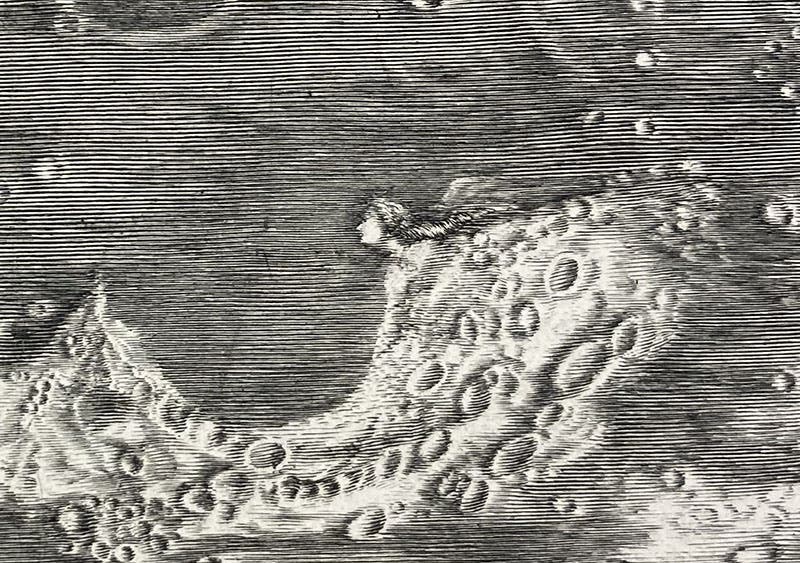

The craters Plato (bottom right), Aristotle (bottom left) , and Eudoxus (top left); the crater at top right, with two smaller craters inside, will later be named “Cassini”, detail of "Carte de la lune de Jean Dominique Cassini," drawn by Jean Patigny, 1787 imprint of 1679 engraving, with South at the top (Linda Hall Library)

Sometime before 1679, a manuscript lunar map was completed by Patigny, no doubt with Cassini standing at his shoulder, and the drawing was then engraved. We don’t know who did the engraving. Claude Mellan, who did his own lunar maps in 1637, has been nominated, but the 1679 engraving, although beautiful, does not display any of Mellan's characteristic techniques. Perhaps Patigny engraved it himself.

Whoever did the engraving, the map is magnificent. It is almost twice as large as the Hevelius and the Riccioli/Grimaldi maps, being nearly 21 inches across (third image). Unlike all other lunar maps to date, it has South at the top, just the way it looks in a refracting telescope. It has no added numbers or labels, so it looks very clean. Not only are all the lunar formations accurately placed and depicted, but there are several endearing added features to charm us: a heart-like formation at bottom left, some fairy-like wings at bottom center, and a tiny figure of a woman with flowing tresses at bottom right, which we see in a detail (seventh image). This "Moon Maiden" is the most famous feature of the Cassini map, and no one is bothered by the fact that she is an illusion. Some think it portrays Cassini's wife, Geneviève, who just happens to have been sketched by Patigny's son not long before the map was completed.

Prints of the original 1679 Cassini moon map soon became impossible to obtain, although the copper plate was retained. Over 100 years later, Cassin's great grandson, Cassini IV, had the plate dusted off and cleaned, and 100 new prints were pulled. The only difference between the two sets of impressions is the legend added at the bottom (South being at the top) to the 1787 imprint: "Carte de la lune de Jean Dominique Cassini" (eighth image)

Last year, we were given a copy of the 1787 imprint of the Cassini map by Frank Manasek, a former collector and dealer, and author of a wonderful guide to lunar maps, A Treatise on Moon Maps: Visual Studies on Paper,1610-1910, which I believe has yet to be officially published, but which has been pre-printed several times; I am happy to have a copy of the preprint. Mr. Manasek decided to dispose of his collection of lunar materials, and we are so pleased that he chose to give some of his collection to us, including the 1787 Cassini map. Since the 1679 impression has been unobtainable for centuries, and the 1787 restrike is of the greatest rarity on the market, we were happy to receive Mr. Manasek's generous gift. He also gave us a copy of the equally elusive 1645 lunar map of Michael van Langren, the first of the three great nomenclature maps, which we also thought we would never obtain. Although Van Langren's birthday and date of death is unknown, we will find an occasion to celebrate this remarkable map within this calendar year.

As for portraits of Cassini, we showed the best-known one in our second post on Cassini; the one we include here (fourth image) showed up recently on Wikipedia, purporting to be at a small civic library in Ventimiglia in Italy, and it appears to be genuine and contemporary, although documentary details are lacking. I hope it turns out to be authentic, so we can leave it up.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.