Scientist of the Day - Howard Carter

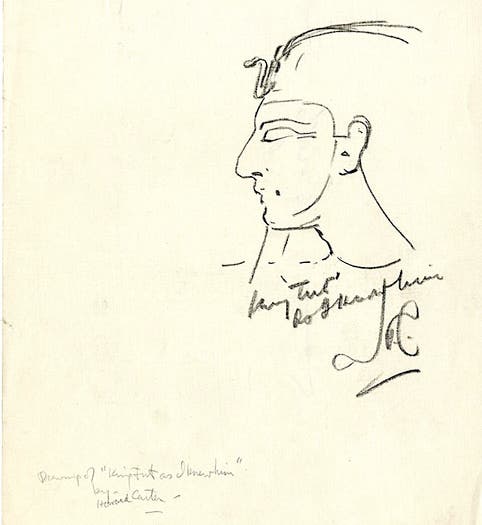

Howard Carter, an English Egyptologist and archaeologist, was born in London on May 9, 1874. His parents were artists, and Carter had considerable artistic talent himself (first image). He was raised in Norfolk and found that he liked to draw antiquities. He went to Egypt in 1891 and learned the art of excavation, and found favor with the Egyptian Antiquities Service. He worked for some years in the Valley of the Kings, the burial site of Egyptian pharaohs on the west side of the Nile at Thebes.

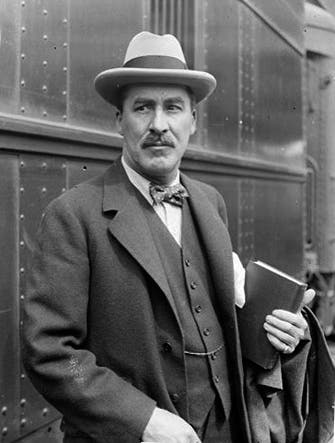

Howard Carter, photograph, 1924 (Wikimedia commons)

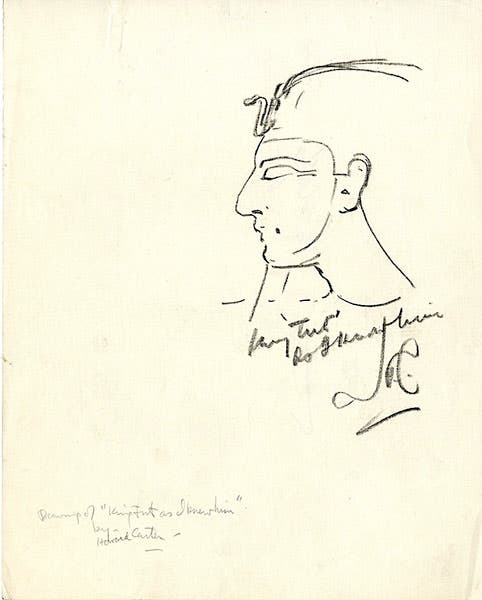

In 1907, Carter was recommended as an excavator to George Herbert, Lord Carnavon, a wealthy patron and collector. Carnavon acquired the rights to excavate in the Valley of the Kings in 1914, and the two men went to work. Most of the tombs in the Valley had been found and looted ages ago. Carter and Carnavon were looking specifically for the tomb of the 18th-dynasty pharaoh Tutankhamun, the only ruler whose remains were unaccounted for. Their search was interrupted by World War I, but Carter resumed work in 1917.

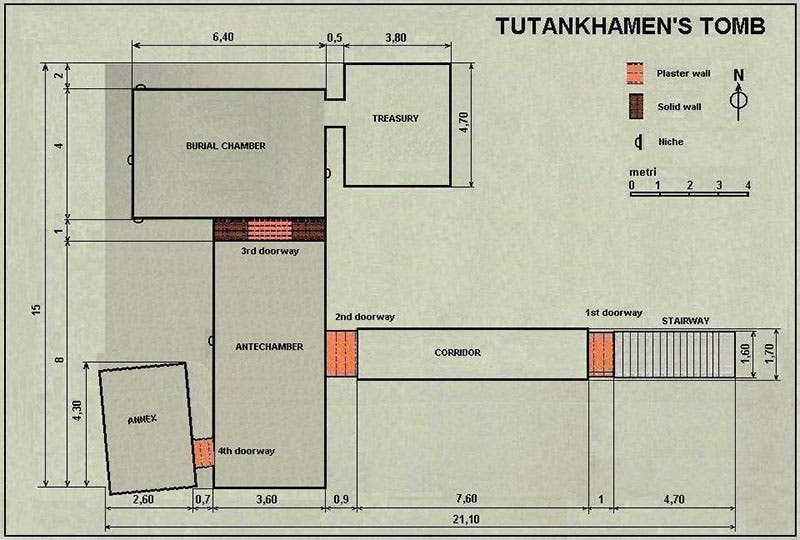

By 1922, Carnavon grew tired of throwing money down the drain, and decided that the fall digging season would be the last. The story of the eventual success of the search for Tutankhamun is a famous one, and there are many dates to celebrate. On Nov. 4, 1922, someone on Carter's team discovered a step under one of the huts in the area. It turned out to be the top of a staircase that led down to a sealed door. Carter filled the staircase back in and notified Carnavon, who arrived on Nov. 23, with his daughter, and the stairway was reopened, and the doorway to the outer corridor unsealed. By Nov. 26, they had emptied the corridor of its rubbish and reached a second sealed doorway, this one to the tomb antechamber. Carter opened a small hole and peered inside. Asked by Carnavon if he saw anything, Carter supposedly answered, "yes, wonderful things." The antechamber was filled with precious artifacts, many of gold. At the far end was a third sealed doorway, this one to the burial chamber.

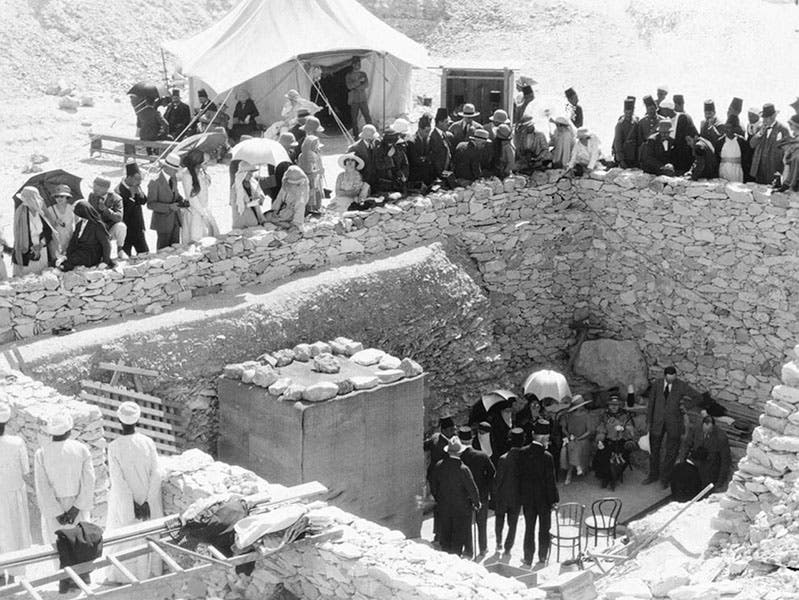

It took months to clear the antechamber, since the wooden objects there deteriorated rapidly. Lots of help was forthcoming, and several nearby tomb corridors were used as sorting and storage areas. The press and tourists began to show up in huge numbers to watch the parade of objects from the antechamber.

Finally, the antechamber was cleared, the doorway to the burial chamber was breached on Feb 16, 1923. revealing that the tomb contents were undisturbed, and on this day, Feb 17, the burial chamber was entered (although there is good evidence that Carter and Carnavon had taken an advance and unauthorized peek back in November).

The find was sensational, although it took another year for Carter to make his way through the nest of coffins down to the innermost one. It did not help that Carter found growing interference from Egyptian authorities intolerable, and that Carnavon died from an infected mosquito bite in April of 1923, initiating stories of the curse of Tutankhamun.

Ove 5000 artifacts were extracted from the tomb before Carter finally ceased work in 1932, including the famous funerary mask (last image). King Tut became famous, Carter not so much, at least in his native land. He really was a crackerjack Egyptologist, yet he never received a single honor from the British government. He was popular on the lecture circuit in the United States for several years, but that died down, and when he died in 1939 of Hodgkin’s disease at age 64, hardly anyone noticed. When his estate was probated, quite a few undocumented objects from Tutankhamun’s tomb were discovered among his possessions. He probably felt he was owed that much from an ungrateful Egyptian government. The misappropriated objects were quietly returned to Cairo.

Most of the photographs here were taken by Harry Burton, who was loaned to Carnavon and Carter by the Metropolitan Museum of Art as soon as the tomb was discovered. Burton was to Egyptian antiquities what Frank Hurley and Henry Ponting were to polar exploration, the best of the best. There have been many exhibitions of his photographs in the past 25 years. He deserves a post of his own here, at some future date.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.