Scientist of the Day - Isaac Newton

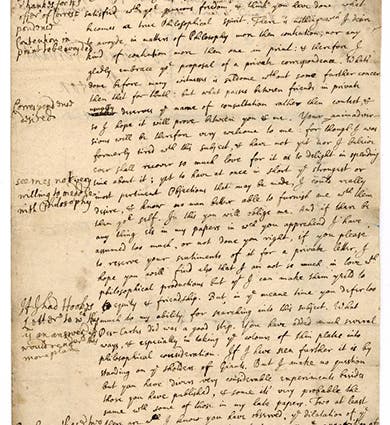

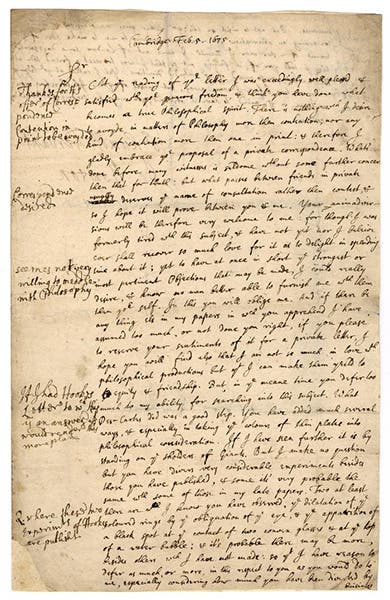

On Feb. 5, 1675/76, Isaac Newton wrote a letter to his older colleague at the Royal Society of London, Robert Hooke. Here is the background.

In December and January, Newton had presented two papers at the Society's regular meetings, in which he offered what was in his opinion a new mechanical theory of light. At the Jan. 20 meeting, Hooke protested that everything Newton outlined could be found in his (Hooke's) Micrographia of 1665. Newton erupted in anger, as Newton was prone to do, and denied that he had taken anything from Hooke, and that Hooke’s theory of light was nothing but Descartes warmed over.

That very day, Hooke wrote a letter to Newton, in which he deplored public controversy, and suggested that they work out their differences in civilized private correspondence, away from the prying eyes of people like Henry Oldenburg, the secretary of the Royal Society, whom Hooke suspected on conspiring against him.

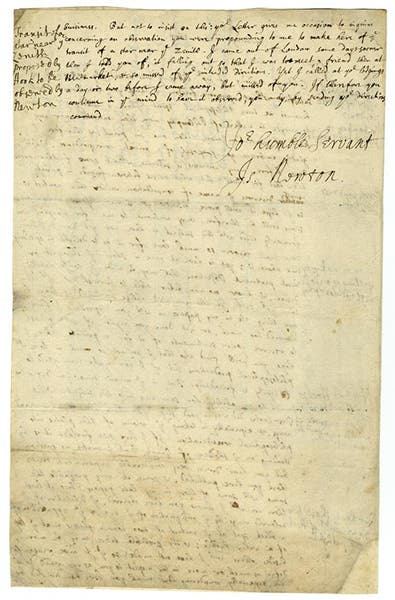

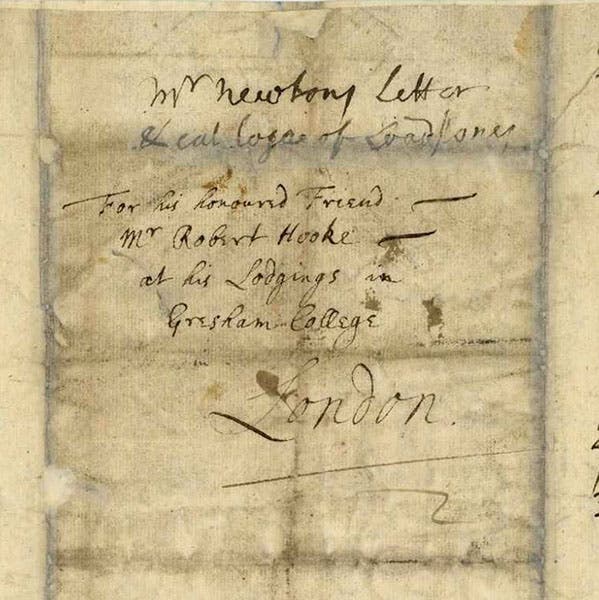

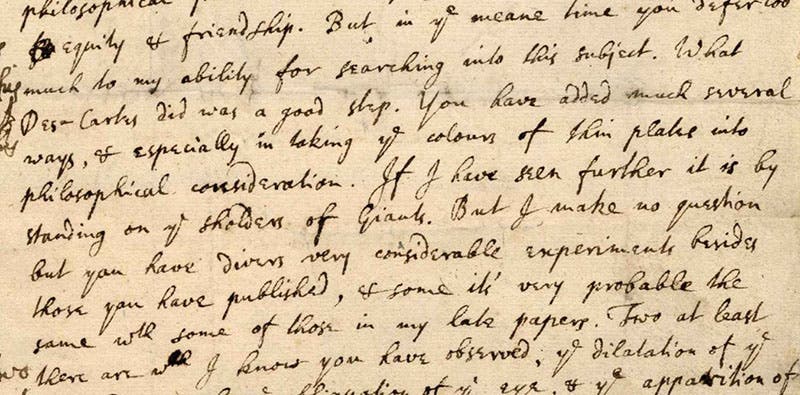

This is the letter that Newton answered on Feb. 5, 1675 (according to the English calendar) or 1676 (according to the calendar in use on the Continent, or by modern reckoning). In it, Newton was fulsome (and duplicitous) in his praise of Hooke, agreed that philosophical debates should not be waged in public or in print, and then wrote, abruptly, “If I have seen further, it is by standing on ye shoulders of giants,” an utterance that was long attributed to Newton as an original aphorism (fourth image). We don’t know that Hooke ever got the letter – he never acknowledged its receipt, as he usually did – but it doesn’t really matter, since Newton didn’t mean any of it anyway. But the Aphorism lived on.

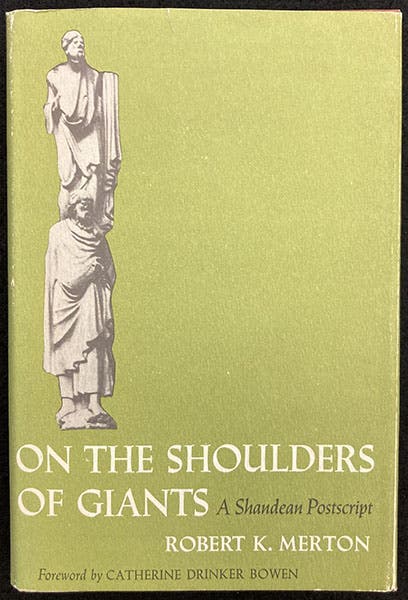

The other reason for celebrating Newton’s first use of the Aphorism on Feb. 5 is that it inspired a mind-boggling discursive piece of historical scholarship that is at the same time a glorious send-up of historical scholarship. I refer to On the Shoulders of Giants: A Shandean Postscript, by Robert K. Merton (1965), which is an uproarious romp through the history of the aphorism, which, it turns out, goes back to medieval times. The book is written in the form of a letter to a fellow historian, and is supposedly written in real time, as Merton chases down references to the Aphorism over quite a few days. In fact, it is carefully constructed to look spontaneous, but is instead mischievously clever, making fun, for example, of the ways odd citations pass from author to author with their oddity unaltered, a pretty good sign that no one is really looking at the cited source. It is a book that every graduate student in history must read (I read it in grad school), and anyone else who is intellectually curious, should read.

Dust jacket, On the Shoulders of Giants, by Robert K. Merton, 1965 (author’s copy)

Merton was a well-known sociologist of science who is best known for the Merton thesis (1938), in which he tied the rise of modern science to the Protestant Reformation, and we wrote a post about that once, under the rubric of Martin Luther. In 1988, I attended a symposium in Jerusalem to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Merton thesis. Professor Merton was there, and we had the chance to chat, and I mentioned to him that while the Merton thesis book was fine, I much preferred OTSOG, the term that in-the-know historians use to refer to On the Shoulders of Giants. When Professor Merton returned to Columbia, he kindly sent me a personalized copy of OTSOG. It is one of the treasures of my library.

Newton’s original letter to Hooke is one of the treasures of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, and they have put it up online, which is the source of my images here. If I ever knew how the letter ended up in Philadelphia, I have forgotten.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.