Scientist of the Day - James Bowdoin II

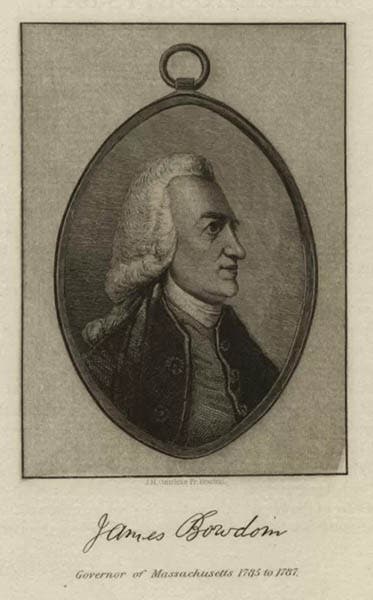

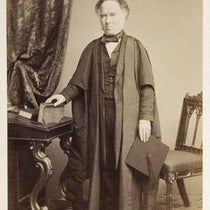

James Bowdoin II, an American statesman and would-be scientist, died Nov. 6, 1790, at age 64; he was born Aug. 7, 1726. Bowdoin inherited wealth and acquired more of his own in the form of land in what is now Maine, which was then part of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. He was active during the Revolutionary War. He ran for governor of Massachusetts in 1780, a race he lost to the popular John Hancock. Bowdoin did become governor in 1785, succeeding Hancock, but then lost the seat back to Hancock in 1787, a result of his perceived mishandling of Shay’s Rebellion.

Bowdoin was one of the founders of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in Boston in 1780 and its first president. Bowdoin had some credentials as a scientist, since he had worked with Benjamin Franklin on some electrical subjects back before the War. The first volume of the Memoirs of the Academy, which we have in the Library’s serials collection, has three papers by Bowdoin on cosmology and the nature of light, but they have never received much attention, perhaps because Bowdoin argued that there must be a large shell of matter surrounding the solar system, in order to neutralize the gravity within and prevent the solar system from collapsing under its own weight. We show you the first paragraph of his first paper, where he mentions Franklin (second image).

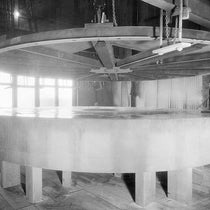

Joseph Pope orrery, completed in 1787, with brass busts and statuettes of Isaac Newon, Benjamin Fannklin, and James Bowdoin II around the base, repeated 4 times, now in the Putnam Gallery, Harvard Science Center; Franklin is the figure at center, Newton is the bust at right, and Bowdoin is to the left of Franklin. (chsi.harvard.edu)

Bowdoin may not have contributed much to the historical steam of science, but he was highly regarded in his day, and when the clockmaker Joseph Pope completed construction of a large orrery (a mechanical model of the solar system, this one some 6 1/2 feet across) in 1787, he graced the perimeter with 3 statues or busts (each figure repeated four times), depicting Isaac Newton, Benjamin Franklin, and, of all people, Bowdoin. We show a detail of one of his statuettes as our first image. Bowdoin was honored presumably because he was Governor, but his presence might also reflect the fact that Bowdoin personally saved the orrery from destruction when a raging fire threatened to (and did) destroy Pope’s shop in 1787, and Bowdoin showed up with a crew of 6 men to move it to safety.

Harvard and everyone else says that the brass figures gracing the orrery, including that of Bowdoin, ”have been attributed to Paul Revere,” but no one provides any evidentiary basis for that statement. I am not familiar with, nor do I have access to, the publications of Paul Revere specialists. But I would think a “yes-or-no” answer to that qualified claim would be out there somewhere.

The Pope Orrery is now part of the Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments at the Harvard Science Center. As soon as we find a date for Pope, we will write more about this remarkable device, one of the very few 18th-century orreries on public display in the United States.

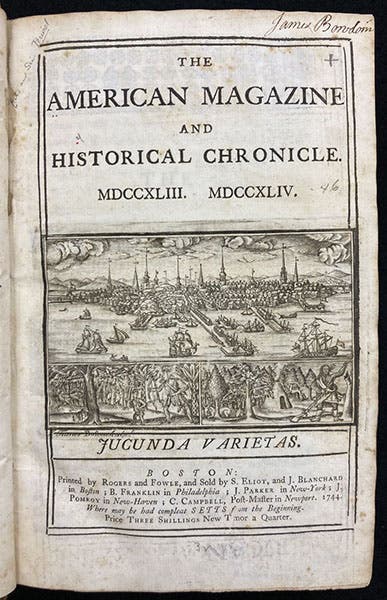

When Bowdoin died, he left his library of 1200 books to the Academy, and since the Linda Hall Library acquired the Academy’s Library in 1946, a considerable number of these must still be in our History of Science Collection. But apparently, Bowdoin was not one to write his name in his books, for only one of our books has his signature, the first volume of the American Magazine and Historical Chronicle for 1743 (fifth image).

James Bowdoin II had nothing to do with the founding of Bowdoin College, which opened its doors in 1794. But Bowdoin’s son, James III, gave the school a tract of land in Brunswick, Mass., soon to be Brunswick, Maine, and considerable funds and his own library, with a proviso that the school be renamed after his father. I used to play squash matches at Bowdoin in my undergraduate days at Wesleyan; it is a lovely campus, well captured in a painting of the 1820s (last image). That is a fine way for James Bowdoin II to be remembered.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.