Scientist of the Day - Jan Evangelista Purkynĕ

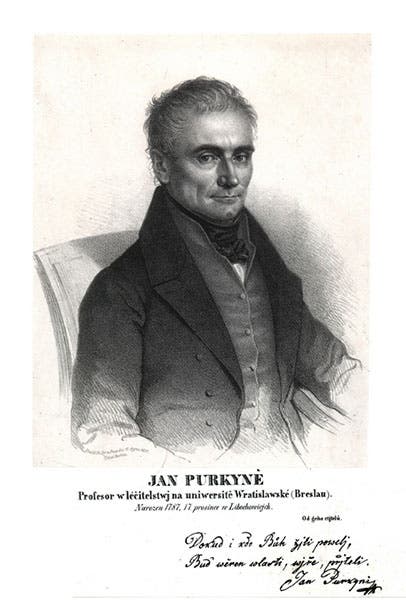

Jan Evangelista Purkynĕ, a Bohemian (now Czech) anatomist and physiologist, was born on Dec. 17, 1787, in what was then part of the Austrian kingdom. He joined a religious order – the Piarists – when he was in his late teens, but soon decided he wanted a different life. He studied medicine at Charles University in Prague, graduating in 1818. He eventually taught physiology at the University of Breslau in Prussia (now Wroclaw in Poland), and then in 1850, he returned to Prague to teach physiology at the medical school there. His name is pronounced "Pour-kien" or "Pour-kin-nee," if you use the spelling we have adopted, but in English-speaking countries, especially in medical schools, his name is often spelled Purkinje and pronounced like it is spelled, which can be confusing.

Purkynĕ took an anatomical approach to physiology, a subject he was one of the first to teach under that name. That is, he studied tissues, using the new achromatic microscopes that became available in the 1830s, discovered new structures, and then tried to figure out their use or purpose (the physiology part). He was exceptionally good at this, and discovered all sorts of anatomical features that still bear his name. For example, he discovered a network of fibers, buried in the inner lining of the heart, that conduct electrical impulses to all parts of the ventricles simultaneously and allow the heart to contract swiftly and smoothly. These are still called Purkinje fibers (usually with that spelling).

Purkynĕ also spent years studying the human eye, using the eye as both the object and the instrument of study. He discovered all sorts of internal reflections that take place within the eye that can be used to study how the eye works. He is somewhat famous for discovering that sensitivity to red and blue light changes when the light diminishes, the human eye being less sensitive to dim red light than blue, so objects change color when the light intensity is reduced. This is called by ophthalmologists the Purkinje effect.

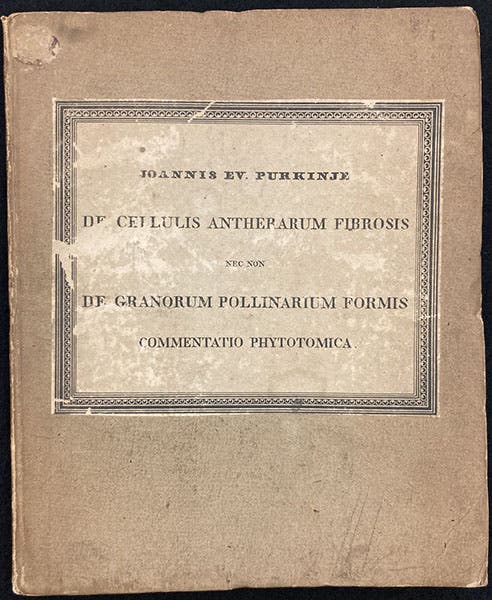

Our library, however, does not have any medical or physiological works by Purkynĕ – that is not what we collect. But we do have one book of his, on botany, published in 1830, just before he started to make a name for himself in medicine. It was a microscopical study of the anthers of a variety of plant species and the pollen they produce. It was called: De cellulis antherarum fibrosis nec non de granorum pollinarium commentatio phytotomica (Phytotomical commentary on the fibers of anther cells and on pollen grains as well; third and fourth images). Vratislaviae is Latin for Breslau.

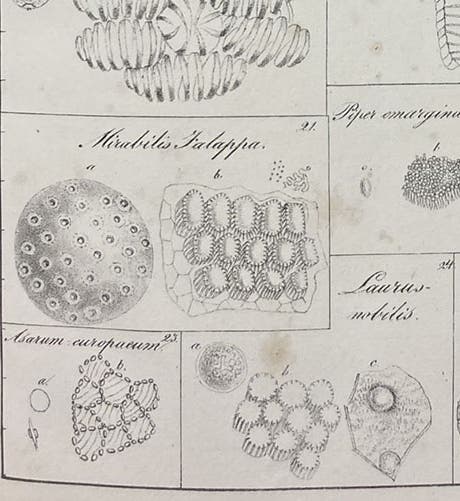

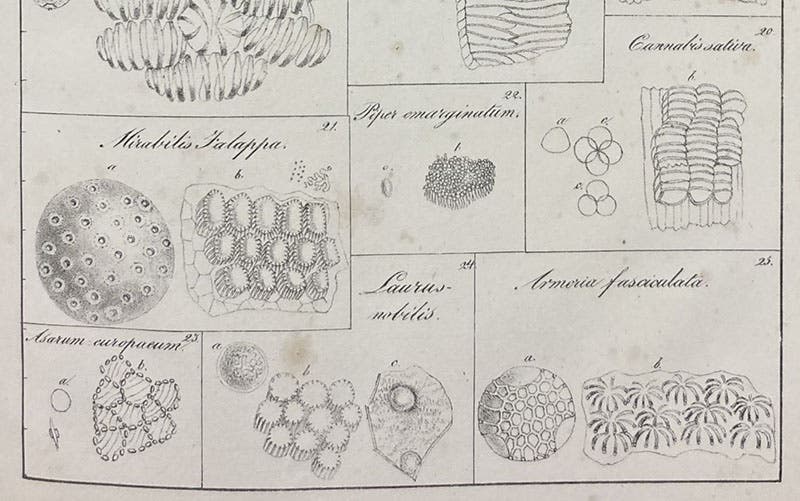

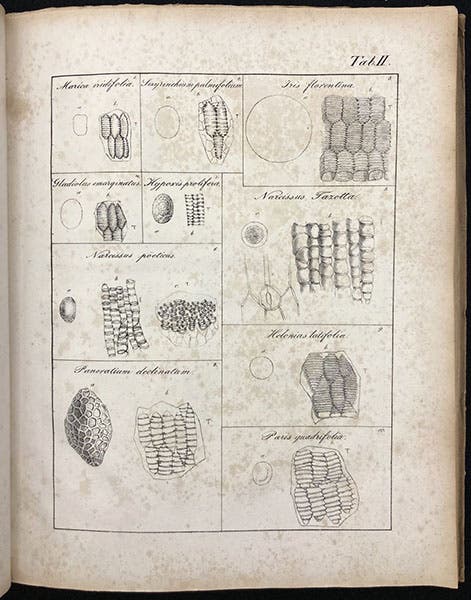

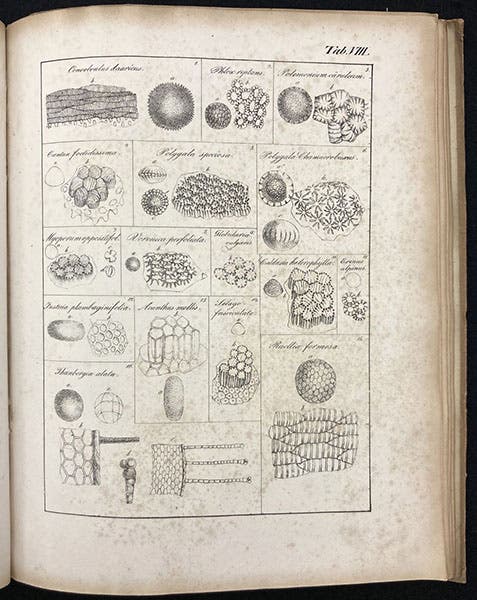

I do not know much about palynology – the study of pollen – but I had thought that palynology as a microscopical science began with a book, Über den Pollen, by the German Carl Julius Fritzsche, published in 1837. This is a book that we do not have in our collections, but it is spectacular, because Fritzsche had access to the new Plössl microscopes coming out of Germany, and the plates are in color and show lots of detail. Purkynĕ's lithographs pale in comparison. But his observations were made with a single-lens microscope, and they do reveal that pollen grains differ markedly from species to species, and they were published 7 years earlier. I do not know if Fritzsche was aware of Purkynĕ’s work, and cited him. Surely some historian of palynology does know, and I hope I hear from him.

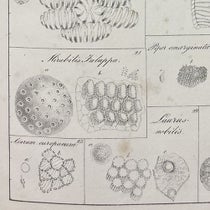

There are 17 full-page lithographs in Purkynĕ’s book, and I show you two of them and lead with a detail from a third. I will point out that the distinctive pollen grain at far left in our opening image is that of a Mirabilis jalapa, also known as the Marvel of Peru or the Four O’clock, and, introduced into Europe from Mexico in the 1530s, has an interesting history of its own.

Purkynĕ is quite a hero to the Czech people, which is probably why we use the Czech spelling of his name. There is a handsome bronze statue honoring Purkynĕ in Charles Square, New Town, Prague (last image)

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![Using an astrolabe to measure the depth of a well, woodcut in Elucidatio fabricae vsusq[ue] astrolabii, by Johannes Stöffler, 1513 (Linda Hall Library)](https://preview-assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/a998eb50-55d2-4a88-ace2-a50aa5fa86e7/Stoffler%201.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)