Scientist of the Day - Jean-André Deluc

Jean-André Deluc (sometimes de Luc), a Swiss physicist and geologist, died in Windsor, England, on Nov. 7, 1817, at the age of 90. He had been born in Geneva on Feb. 8, 1727, and although well-educated, he worked in the business world until 1773, although he frequently hiked in the Alps and collected fossils and minerals.

In 1773, Deluc abruptly left Geneva – supposedly some business venture went sour – and moved to England, where he somehow came to the attention of Queen Charlotte, wife of King George III, and he became her tutor, and held that position for the rest of both of their lives – she died in 1818, a year after Deluc. It does not appear that Deluc tutored any of the royal couple's 13 children, just Charlotte. It was the perfect job for a would-be natural philosopher, since it provided Deluc with a secure income and the opportunity to travel.

With his geological and paleontological interests, Deluc soon became caught up in debates about the geological history of the Earth, which came within a genre known as Theories of the Earth. Deluc was opposed to the tendencies, especially those of the French, such as Descartes and the Comte de Buffon, to completely discard the account of creation provided by Genesis. Deluc was what he liked to call a Christian philosopher, who believed that the divine revelations related in Scripture were compatible with the truths revealed by empirical inquiry. He was not at all a fundamentalist, and he did not advocate for a literal reading of Genesis. But he did believe that humanity was a relatively recent introduction to the Earth, and that the Flood was a real historical event.

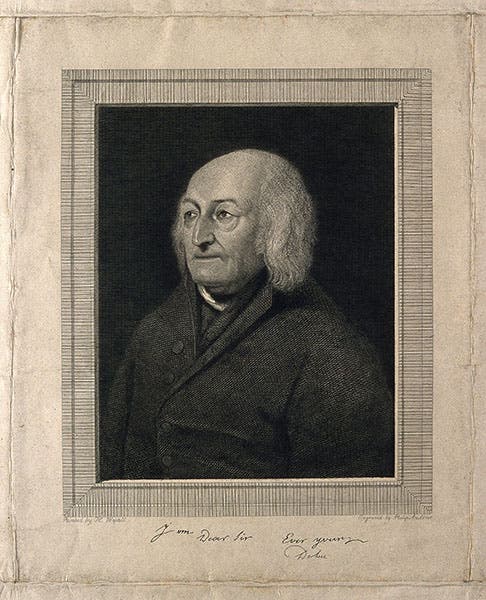

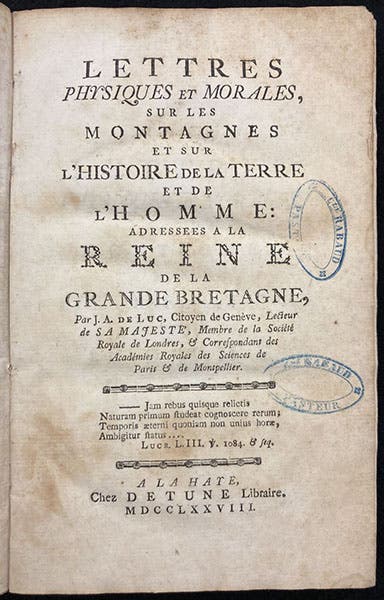

In 1778, Deluc began publishing Lettres physiques et morales sur les montagnes et sur l'histoire de la terre et de l'homme, in the form of letters to the Queen. He started with 15 letters, which he published in a stand-alone volume in 1778 (second image), but he kept writing letters, and eventually published 148 letters in 5 volumes, 1779-80 (third image). We have both the single volume and the set in our History of Science Collection. Deluc was not so much interested in causes as he was in determining exactly what happened to the Earth in the past, as determined by observation. His principal conclusion was that the present continents were a recent innovation, having risen from the ocean floor, as land and sea floor exchanged places. This would account for the wide distribution of marine fossils in mountains like the Alps.

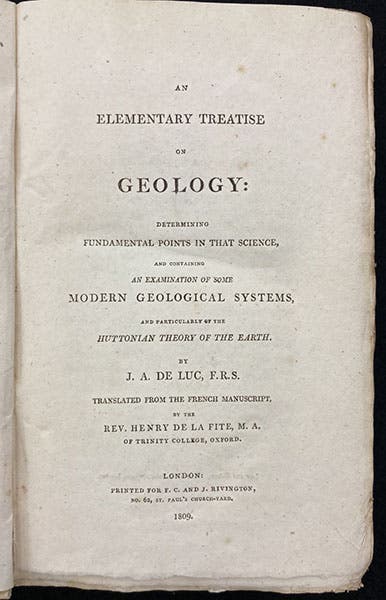

In the 1790s, Deluc had to deal with the challenge of James Hutton's Theory of the Earth (1795), where Hutton rejected catastrophic explanations and argued that the Earth changes slowly but inexorably due to small forces such as erosion and uplift due to heat. Hutton found no evidence that the Earth had a beginning in Time. In his response, Deluc took Hutton to task for not doing enough to counter the tendency toward atheism implicit in his uniformitarian geology, in a book called Traité élémentaire de géologie (1809). We show the title page of the English translation of the same year, because it mentions Hutton, unlike the French edition, which we also have (fourth image).

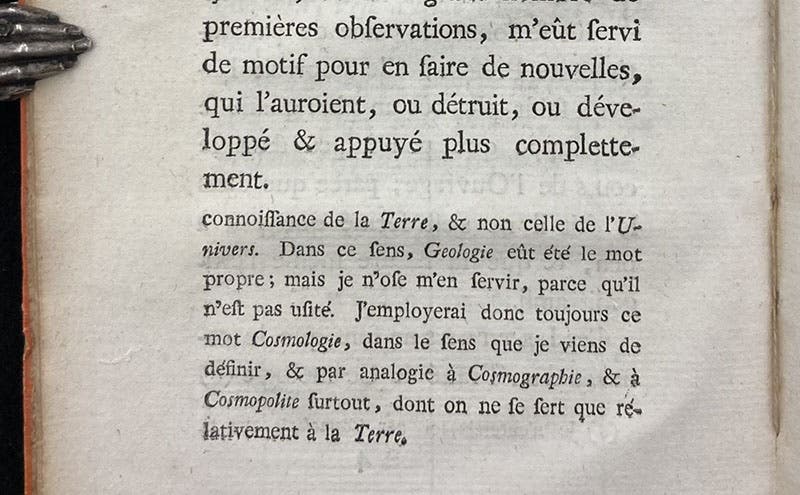

Unlike many Scriptural geologists, Deluc was taken seriously by proponents of various other Theories of the Earth, because of his attention to geological facts. Indeed, Deluc invented the word "geology", as a counterpart to the astronomer's "cosmology", although he meant by it something other than general earth science. You can see the first use of it in the introduction to the 1778 edition of his first 15 letters to Charlotte (fifth image).

We included Deluc’s Elementary Treatise on Geology in our exhibition, Theories of the Earth, 1644-1830: The History of a Genre (1984), the first exhibition that Bruce Badley and I did for the Library (sixth image). We should have included the Lettres physique et morales as well, but ran out of room.

The best guide to Deluc and his place in late 18th-century geology is Martin Rudwick’s Bursting the Limits of Time: The Reconstruction of Geohistory in the Age of Revolution (2005). If you go to check it out at your local library, bring a small wagon to help you get it to the car. Rudwick points out a feature of Deluc’s persona that I had noticed back when we did the exhibit: Deluc had no visual sense, and no use for images. There is not one illustration in any of the books we have mentioned. As one who is image-driven, I cannot imagine writing (or reading) a book on geology with no visual references whatsoever. Humans do have fundamental differences in makeup. As if I needed proof of that these days!

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.