Scientist of the Day - John Turberville Needham

John Turberville Needham, an English microscopist, experimental naturalist, and Catholic priest, was born Sep. 10, 1713. Like many English Catholics, he was educated abroad, in this case at the English College at Douai in the Netherlands. He then taught at the English College in Lisbon, where he began investigations with the microscope, discovering all manner of tiny living things, which he detailed in his first book, An Account of Some New Microscopical Discoveries (1745). We discussed these discoveries in our first post on Needham, where we also showed some of the 6 plates in the book, depicting barnacles, sole-embryos, and animalcules of various kinds.

By the time his first book was published, Needham had moved to Paris, carrying a letter of introduction from the President of the Royal Society of London to Georges Buffon, who was then working on the first volumes of his Histoire naturelle (1749-1804), and who pulled Needham into the lively topic much debated in the 1740s, how living things ae generated, and the side topic, the possibility of spontaneous generation.

The alternatives at the time were that each living organism developed from an unformed (homogeneous) egg according to some built-in vital plan, a process called epigenesis, or that the organism was already fully formed in the egg, or the sperm, and simply had to grow and develop, which was called preformation. Although consistent preformationism required that the germs of every future living human be pre-existent in the loins of Adam and/or Eve, it was the preferred view, because it could be understood mechanically, as simple growth, without recourse to any vital forces. There were two camps of preformationists: ovists, who thought the preformed embryos were within the female egg, and the animalculists, who thought the male sperm carried the preformed seeds. Both schools denied spontaneous generation, since it required a vital, non-mechanical force to draw life from non-living matter. Buffon was a vitalist, who postulated the existence of " organic molecules" which could congregate and aggregate and form an endless variety of living things, without eggs or seeds. In Buffon's world, spontaneous generation was everywhere, at least on a large scale..

Needham was intrigued by Buffon's vitalism, and decided to look for evidence for spontaneous generation on a smaller scale. Although spontaneous generation went back to Aristotle, who thought worms and flies were generated in rotting meat, Francesco Redi in 1669 had supposedly refuted the idea with an ingenious set of experiments in which he gave some vials of decaying meat access to air, and covered others with gauze to keep out flies, and found that if you keep flies off the meat, no worms appear, suggesting that the worms come from eggs laid by flies. But Redi didn't know about microscopic life, because the microscope had just been invented. Needham decided to redo Redi's experiments, and use the microscope to look for evidence of spontaneously induced life.

Description of the “mutton-gravy” experiment, “A Summary of some late Observations upon the Generation, Composition, and Decomposition of Animal and Vegetable Substances,” by John Turberville Needham, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, vol. 45, p. 637, 1748 (Linda Hall Library)

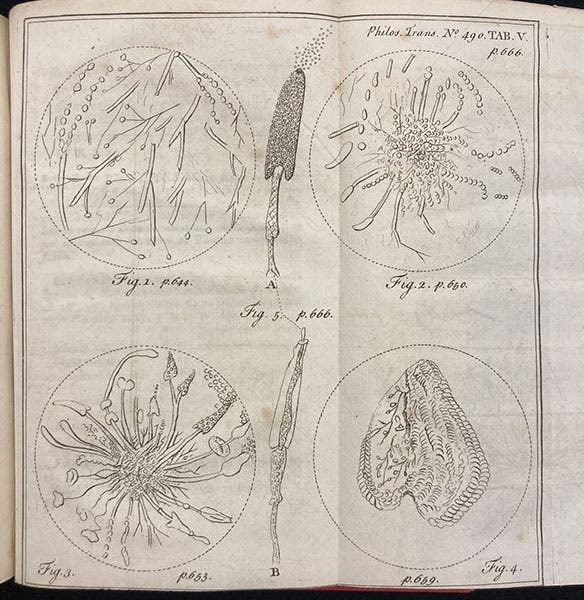

Needham announced his results in a paper published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society in 1748 (first image). He put vegetative matter in vials, sealed them with cork, hearted them for extended periods, and found the contents to be teeming with microscopic life. In his most famous experiment, he took "mutton-gravy hot from the fire," sealed it up and heated it, and life still found a way to appear (third image). A plate at the end of his paper shows the various infusions of wheat and "paste-eels" that he used for his experiments, which proved to his satisfaction that there is a vegetative force in nature that can produce living things without eggs or seeds (fourth image). I also include the caption to the figures, which was placed just opposite the plate (fifth image).

Plate showing infusions of wheat and eels used in his experiments, “A Summary of some late Observations upon the Generation, Composition, and Decomposition of Animal and Vegetable Substances,” by John Turberville Needham, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, vol. 45, plate 5, opp. p. 666, 1748 (Linda Hall Library)

Part 2 of this story began when Lazzaro Spallanzani, an Italian preformationist who was also a priest, decided to redo Needham's experiments, but more rigorously, to show that life will not arise when vessels are properly sterilized and hermetically sealed. He published his book in 1765. Four years later, Needham had the book translated into French and published, along with his own notes, which were longer than Spallanzani's original book. We have the 1769 Spallanzani/Needham edition in our collections, and when Spallanzani's birthday, Jan. 12, next rolls around, we will look at the next stage in the persistent life of spontaneous generation. This will go on until we finally reach Louis Pasteur.

Apparently, there is only one surviving portrait of Needham, a watercolor in the National Portrait Gallery in London. We used it in our first post, but we have to use it again, of we would have no portrait today. I cropped it a little this time, just to give it a different look.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.