Scientist of the Day - Joseph Banks

Joseph Banks, an English botanist, voyager, and patron, was born on Feb. 13 (O.S.), 1743, in London. His father was a wealthy country squire with an estate in Lincolnshire, which Joseph would inherit before he was 21, making him a very rich man. He is best known for organizing, financially supporting, and participating in James Cook's first voyage around the world in 1768-71. He brought back tens of thousands of plant specimens and had plates engraved of his herbarium that were not published until 1980. We have a set of these and wrote a post about them in 2023.

Plans to accompany Cook on his second voyage (1772-75) went awry, and instead Banks made a trip to Iceland and the Hebrides, which we discussed in a earlier post of 2015. But by 1773, Banks had settled down in London, where he spent the rest of his life, supporting all sorts of scientific endeavors, many involving botany, his first love, but many related to the physical sciences.

When King George III decided to establish a Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew in 1773, he turned to Banks first for advice. Banks found him a head Gardener, William Aiton, and sent collectors around the world, but especially to South Africa, Australia, and South America, at his own expense, to secure seeds and living plants that would thrive at Kew. He kept this up for almost 40 years. As far as I can tell, he never had a formal position at Kew, but when Aiton was asked who ran the place, he answered emphatically: Banks.

Banks’ interest in physical science began when he was elected President of the Royal Society of London in 1778. He held that post for over 41 years, until his death in 1820. With his wealth, and in that position, he became the most powerful scientific voice and patron in the world. He was very proud of what members of the Royal Society were accomplishing, and he sent out letter after letter to correspondents around the world, informing them of what was going on in London, something that formerly was done by the secretaries. I remember being struck by a letter that Banks wrote in 1800 to Martinus van Marum, a Dutch electrical experimenter and founder of Tylers Museum in Haarlem, saying, essentially, you should look at the latest volume of the Philosophical Transactions, where William Herschel reveals that he has discovered infrared radiation, and also Alessandro Volta describes the invention of the battery. When Humphry Davy burst on the scene shortly thereafter, Banks extolled his work to anyone who would read his letters.

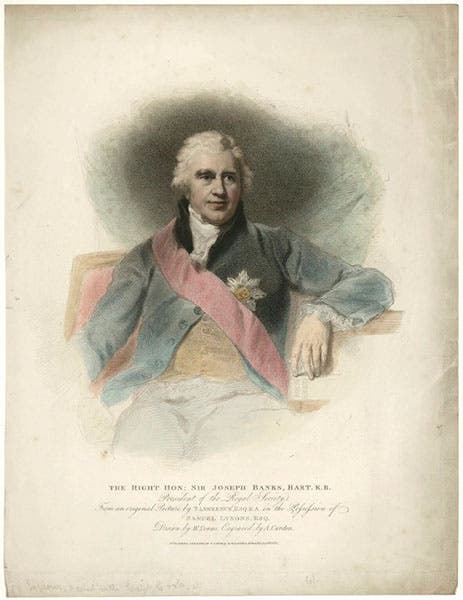

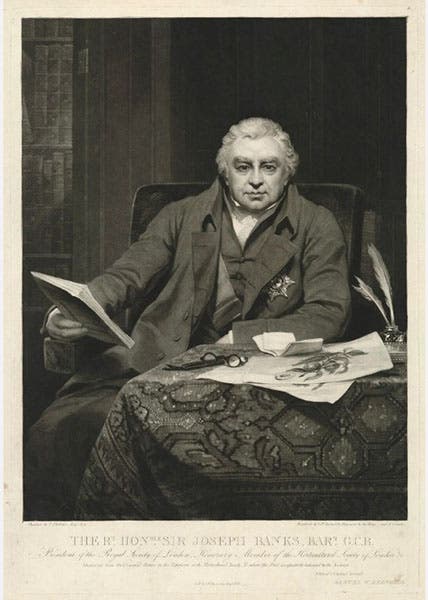

Joseph Banks, oil on canvas, by Thomas Phillips, 1810, National Portrait Gallery, London (artuk.org)

Banks was also an avid collector of naturalia and books, which he amassed in his house at 32 Soho Square, which was kept in order by Daniel Solander, his botanist on the first Cook voyage, and then by Robert Brown, the botanist on the Flinders voyage. Brown later went to work for the British Museum, and as a result, the bulk of Banks’ collection (like the 738 unpublished copper plates of his herbarium) ended up there, except for his correspondence, which somehow wound up in Australia.

Banks was also the spearhead of the African Association, which first met in 1788 at a London pub and lasted for some 43 years. The mission was to encourage and support the exploration of Africa's interior, especially along the Niger River. Their only income came from dues, which they dispensed to anyone who came before them and laid out a plan. If Banks liked the cut of your jib, then off you went, usually to an early death, but at least it was paid for. Mungo Park and Johann Burckhardt were both beneficiaries of African Association grants.

Banks suffered for the last few decades of his life from gout, which grew so severe that he was unable to walk. It probably did not help that he ate and drank heartedly and was seriously overweight. If you wanted to consult Banks after 1810, you went to 32 Soho Square. He bore the pain of his affliction stoically, by all accounts.

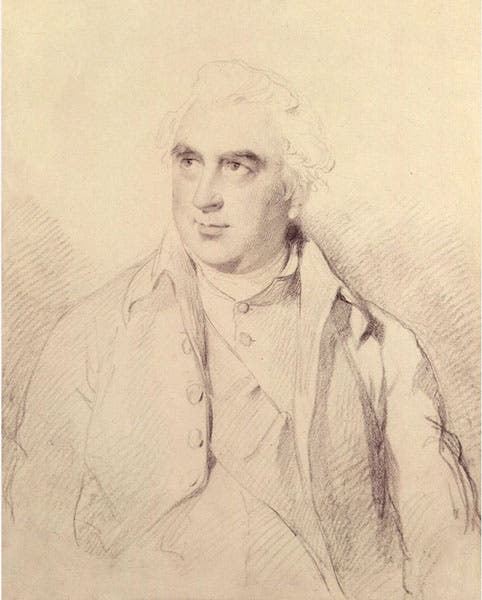

Because of his wealth and fame, Banks's portrait was painted many times by England's best portrait artists. My favorite, because it shows Banks the explorer, was painted by Joshua Raynolds right after his return with Cook in 1771 – we showed this one in our last post on Banks. The other famous early portrait, depicting Banks in a Maori cloak, was painted in 1772 by Benjamin West, and it leads off our parade of portraits here. The portrait by Thomas Phillips, our fourth image, depicting an older and rounder Banks, was the basis for many engravings and mezzotints, of which we show one (last image).

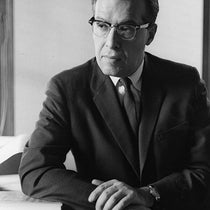

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.