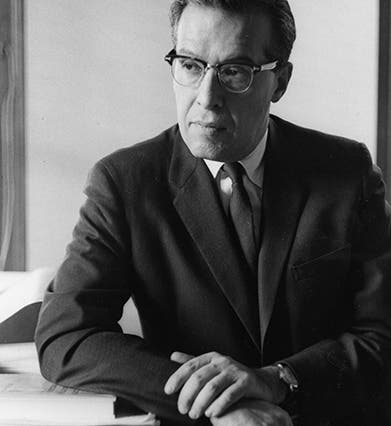

Scientist of the Day - Julian Schwinger

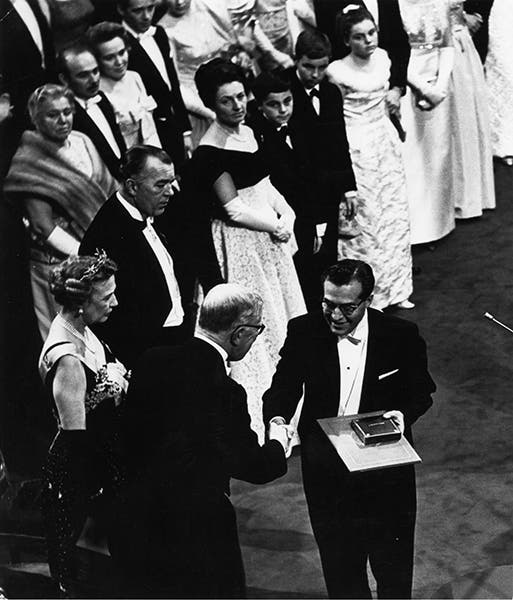

Julian Schwinger, an American physicist, was born on Feb. 12, 1918, in New York City. Schwinger was one of three to win the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1965 for revitalizing the field known as quantum electrodynamics, or QED. In the public mind's eye, Schwinger has long been in the shadow of one of his co-awardees, Richard Feynman. But Schwinger was every bit his equal (as was the third awardee, Sin-itiro Tomonaga, working in the impossible conditions of post-war Japan).

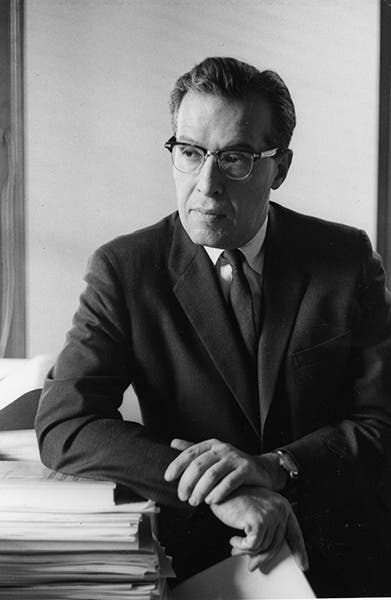

Group photo of participants at the Shelter Island Conference, June 2-4, 1947; Schwinger is at the center of the front row, with clutched hands; Feynman is third from the right in the back; Oppenheimer is fifth from right; Bethe with frizzled hair is ninth from the right in front of the window, just behind John Wheeler; photograph property of the Julian Schwinger Foundation (schwingerfoundation.org)

Schwinger was the son of savvy Ashkenazi Jews who thrived in the commercial environment of New York City. His mathematical talents were recognized early, and he attended good schools and was accepted tuition-free into NYU. He ran into trouble, as did Feynman not far away in Far Rockaway, with his total lack of interest in the humanities and social sciences, but when he transferred to Columbia, he found a more comfortable situation. He had caught the eye of Isidor Isaac Rabi at Columbia, who secured Schwinger a scholarship and oversaw his PhD, which Schwinger received in 1939. During the War, Schwinger worked at the Radiation Lab at MIT (while Feynman was designing fission bombs at Los Alamos), and he got his first teaching position at Purdue. After the war ended, Schwinger joined the faculty at Harvard, where he would teach until 1974.

Renormalization in progress at the Shelter Island Conference, 1947; Feynman, in the center on the couch, draws diagrams for Schwinger, at right on the floor, while another prodigy, John Wheeler, does his own thing at the back; Willis Lamb, whose discovery of the Lamb shift was a major topic of discussion at Shelter Island, stands at left; photograph property of the Julian Schwinger Foundation (schwingerfoundation.org)

The big moment for both Schwinger and Feynman came in 1947, at the Shelter Island Conference of that year. Duncan MacInnes and Karl Darrow, two scientists appalled by the large and unproductive academic annual meetings typical of post-War America, attended by thousands of scientists, where nothing got accomplished, wondered if it might be possible to bring together only the very best physicists, give them a topic, feed and seclude them for 3 days, and see what happens. They obtained support, physicists were eager to come, and 25 or so of them met on June 2, 1947, at Ram's Head Inn on Shelter Island, at the eastern tip of Long Island, between the two forks. It helped that one of the invitees, Willis Lamb, had just made a measurement of something called the Lamb shift, which revealed a serious discrepancy in the quantum mechanics established by Paul Dirac (who was not at Shelter Island – English and continental physicists were not invited). Hans Bethe was there, and Robert Oppenheimer, but it rapidly became apparent that the two stars of the show were the promising unknowns, Feynman and Schwinger. They found separate ways of solving the problem of the Lamb shift by inventing a process called "renormalization," where the infinities that were popping up in the quantum equations were resolved by some tricky but legitimate mathematical maneuvers. Feynman did this with little vector diagrams, which came to be called Feynman diagrams; Schwinger did it with field equations. Both systems worked, and QED was saved. It was not until 1949 that Freeman Dyson, a young English mathematician who was visiting Cornell and Princeton and was not invited to Shelter Island, showed that the approaches of Feynman and Schwinger were equivalent and produced the same results.

I am not sure how well Feynman and Schwinger got along. They certainly respected each other's abilities. But they were such different personality types that ordinary social discourse must have been awkward at best. It is nice that the world of physics had room for them both. And for Sin-itiro Tomonaga, whose story we told in a post last year.

Schwinger died of pancreatic cancer in 1994 and was buried in Mount Auburn Cemetery outside Cambridge, Massachusetts.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.