Scientist of the Day - Leonhart Fuchs

Leonhart Fuchs, a German botanist, was born Jan. 17, 1592, in Wemding, a small town in Bavaria. He was a precocious child, and was sent at the age of 11 to the University of Erfurt. He then went to the University of Ingolstadt, where he received his M.A, and began to study medicine. At Ingolstadt, he converted to the new faith of Martin Luther (who had also attended Erfurt), which was odd, as Ingolstadt was firmly Roman Catholic. Uncomfortable at Ingolstadt, he became the personal physician of Georg, Margrave of Brandenburg-Ansbach. But in 1531, he was offered a faculty position at the University of Tübingen, which he accepted, and he would stay at Tübingen until his death in 1566.

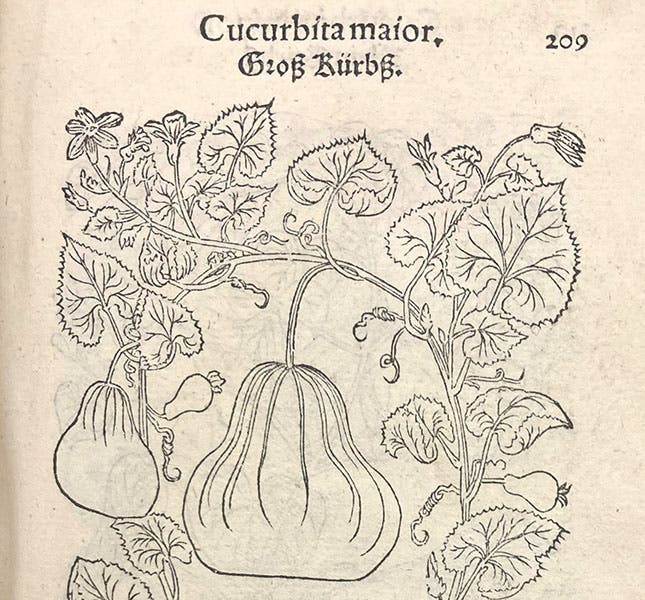

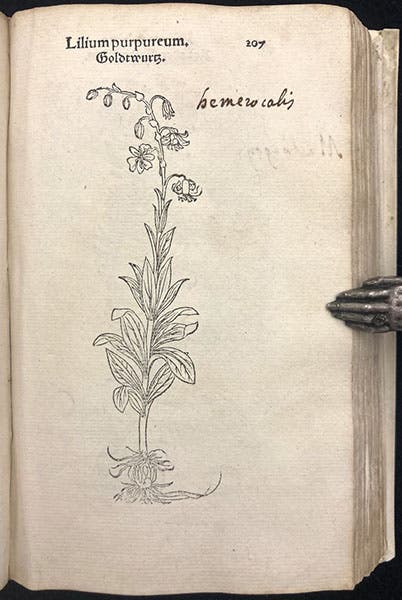

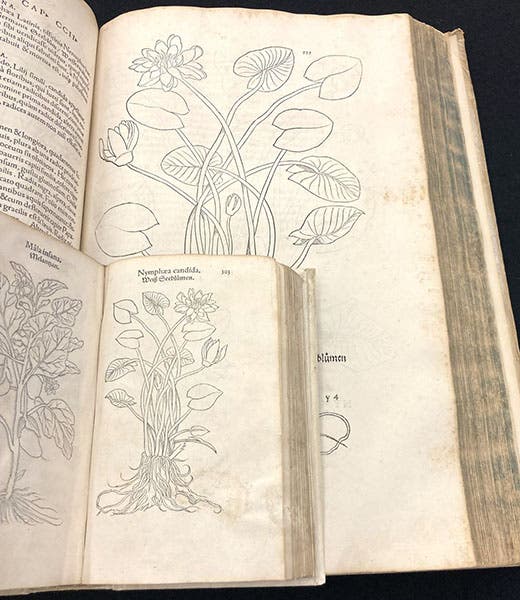

Fuchs began teaching at Tübingen the year after Otto Brunfels published the first volume of his Herbarum (1530-32), the first botanical work with illustrations drawn from life, provided by the artist Hans Weiditz. Fuchs was an immediate convert to this new kind of botanical book, and he soon embarked on a similar project of his own. Fuchs was a humanist, meaning he found his principal botanical inspiration in the works of ancient botanists, the Greeks Hippocrates, Dioscorides, and Galen, so his book would illustrate the plants described by the Greeks, to the exclusion of most of the Arabic commentators. And whereas Weiditz had depicted Brunfels’ plants at an instant of time, and had shown them with all their natural imperfections, Fuchs chose to provide illustrations that were realistic but deliberately unnatural, in that they show all the various stages of budding, flowering, and fruiting in one woodcut. He hired the best artists and woodcutters for his project, and De historia stirpium was published as a tall folio in 1542. It had 512 full-page woodcuts of plants (plus a triple portrait of his artists, and one of himself), and it almost instantly changed the look and content of the medical herbal. We wrote a post on Fuchs in 2019, in which we showed several plant woodcuts (and the two portraits) from the 1542 edition, which we have in our collections.

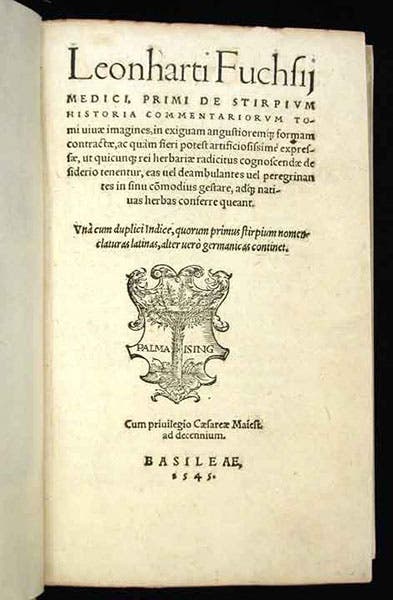

Today, we are going to look at a second herbal that Fuchs published three years later, and which we mentioned at the very end of our first post. Surprisingly, to modern sensibilities, Fuchs’ inclusion of and dependence on illustrations was criticized by many contemporaries, who believed that the ancient Greek texts of Dioscorides and others provided the only sure knowledge of medicinal plants, and that images were often deceiving, especially if they showed the wrong plant.

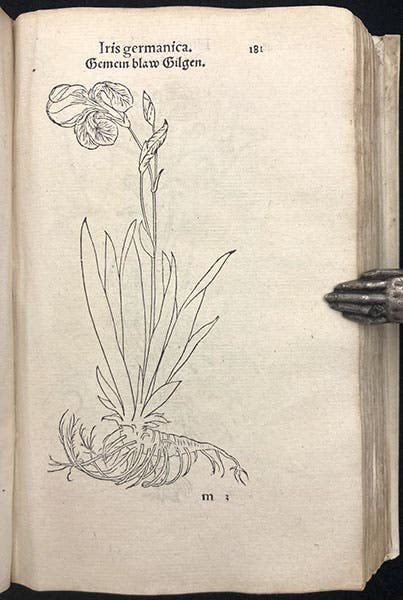

Fuchs stood by his guns, and as if to make the point that modern illustrations could be a reliable guide to ancient plants, he decided to issue a small octavo version of his 1542 herbal, with all the 512 woodcuts greatly reduced in size, and eliminating the text entirely, except for simple captions.

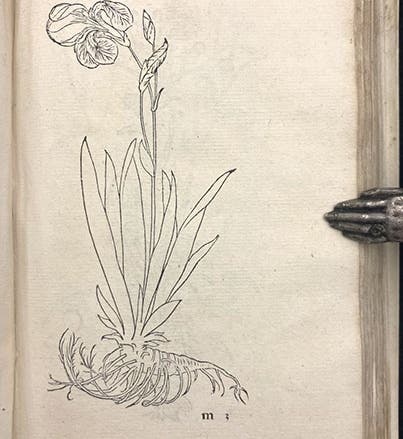

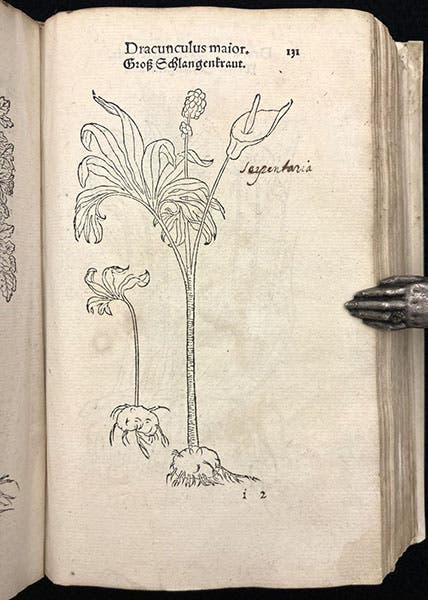

All of the woodcuts reproduced here are from our copy of Fuchs’ Primi de stirpium historia (1545), the short-title that we use for this work (third image). We chose mostly plants that will be familiar to you, such as the bearded iris (first image) and a dragon arum (fourth image). The woodcut of a squash plant is shown in detail, so that you can see the different stages of buds, flowers, and fruits (fifth image). The woodcuts of the iris and daylily (sixth image), with their outline form and complete lack of shading, indicate that the woodcuts were intended to be colored, although many copies, such as ours, were not.

The other attraction of the octavo format is that the book could now be used as a field guide, which was certainly not the case with Fuchs’ 1542 folio, or any other herbal of the day, none of which were portable. I suspect that Hieronymus Bock, whose octavo herbal of 1539 was unillustrated, was inspired by the success of Fuchs’ octavo to re-issue his own herbal in 1546, now supplemented with small woodcut illustrations like those Fuchs had provided.

Because I could, I took a photo of the 1545 octavo Fuchs herbal, lying atop the 1542 folio, with both books opened to the Nymphaea candida, the white water lily (seventh image, just above). We see not only the difference in size, but we are reminded that when woodcuts are copied, they invariably end up being reversed, right to left.

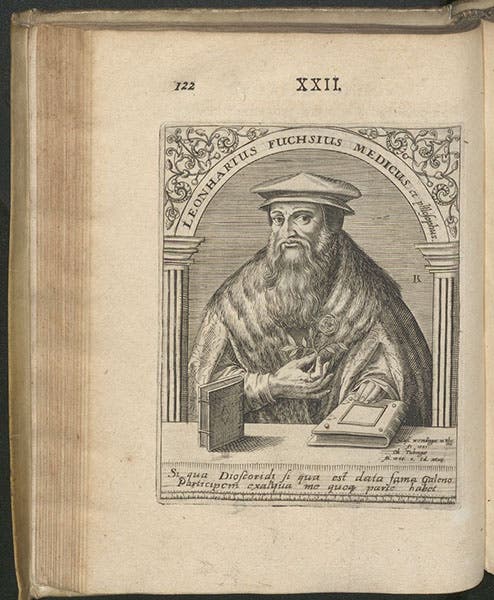

In our first post on Fuchs, we showed the full-page woodcut portrait from our 1542 edition (which in many copies is richly colored). Since the portraits were not reduced and included in the 1545 octavo edition, we show, for his occasion, a different portrait of Fuchs, taken from our four-volume set of Jean-Jacques Boissard’s Icones quinquaginta virorum illustrium (1597-99), with engravings by Theodor de Bry (second image).

Picturing the Book of Nature: Image, Text and Argument in Sixteenth-Century Human Anatomy and Medical Botany, by Sachiko Kusukawa (Univ. of Chicago Press, 2012) is an excellent resource on both editions of Fuchs’ herbal, and on other early modern herbals as well. And there is a beautiful reproduction of a colored woodcut portrait of Fuchs, from the Cambridge Library copy of the 1542 edition, on the dust jacket.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![Using an astrolabe to measure the depth of a well, woodcut in Elucidatio fabricae vsusq[ue] astrolabii, by Johannes Stöffler, 1513 (Linda Hall Library)](https://preview-assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/a998eb50-55d2-4a88-ace2-a50aa5fa86e7/Stoffler%201.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)