Scientist of the Day - Lodovico delle Colombe Colombe

Lodovico delle Colombe, a Florentine Aristotelian philosopher, was born on Jan. 20, 1565 (perhaps). There is no known portrait. He is best known for being a persistent thorn in the side of Galileo for ten years.

Colombe’s thorniness first manifested itself when a new star appeared in the heavens in 1604, the nova now known as Kepler’s Nova, which was in fact a supernova and for a while as bright as Mars or Jupiter. Galileo, then in Padua, gave public lectures in which he argued that the star was really new, a counter-example to the Aristotelian doctrine that the heavens are permanent and unchanging. Colombe published a book in 1606 in which he defended Aristotle and denied the novelty of the star. We do not own this work – indeed we don’t have anything by Colombe in our collections. His publications, ephemeral to start with and held in little regard by Galileo’s circle, have not survived in great numbers.

Colombe also published a book opposing Galileo’s suggestion in his Sidereus nuncius (1610) that the earth is a planet orbiting the Sun. Galileo, now in Florence, was attacked from the pulpit by three Dominicans, one of whom was Colombe’s brother Rafaello. Lodovico seems to have joined forces with the three Dominicans in opposition to Galileo, an alliance that was called, by one of Galileo’s friends, the League of Pigeons, a punning reference to Colombe, which means “dove” in Italian.

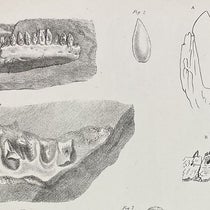

The big clash came in 1612, when Galileo published a treatise on floating bodies, a book that we have in our collections (second image). Galileo followed Archimedes rather than Aristotle, arguing that density is the key to understanding whether something floats or sinks, and maintaining that ice must be less dense than water, since it floats on water. Colombe published a book arguing that shape rather than density is the key. An object thin and flat might float, while another object of the same density, round and compact, might sink.

Galileo did not think much of Colombe or his physics, and he did not want to dignify this attack with a personal reply, so he asked a pupil, Benedetto Castelli, to draft a response to Colombe, and Castelli did so. His treatise was published in 1615 as Risposta alle opposizioni del s. Lodovico delle Colombe, e del s. Vincenzio de Grazia, contro al trattato del sig. Galileo Galilei, delle cose che stanno su` l'acqua, o` che in quella si nuouono (Response to the objections of Mr. Lodovico delle Colombe and Mr. Vincenzio de Grazia against the treatise of Mr. Galileo Galilei on things that float on water or move in it) (first and third images). It is the capstone of Galileo's work on floating bodies. We acquired this very scarce book just last year, and its acquisition provides the main justification for granting Colombe the status of being a Scientist of the Day. It would be nice to acquire Colombe's book someday, so visiting scholars could see firsthand what Galileo and Castelli were reacting against.

After Castelli's book appeared, Colombe disappeared from Florentine polemics, and Galileo soon had a new set of critics, since he was called to Rome in 1616 and interviewed by Cardinal Bellarmine concerning his Copernicanism. Colombe was last heard of in 1623, so he presumably died around then, although he was a year younger than Galileo.

There is a statue of Galileo in Florence along the arcade below the Uffizi (fourth image), and it is presumably visited regularly by pigeons, since everything in Florence is visited by pigeons. I would not be surprised if the ghost of Colombe is among them, cooing Aristotelian dogma into the stony ear of the founder of modern physics.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![Columbine, hand-colored woodcut, [Gart der Gesundheit], printed by Peter Schoeffer, Mainz, chap. 162, 1485 (Linda Hall Library)](https://preview-assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/3829b99e-a030-4a36-8bdd-27295454c30c/gart1.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)