Scientist of the Day - Martin Gardner

Martin Gardner, a recreational mathematician, or perhaps mathematical gamester, was born Oct 21, 1914, in Tulsa. He attended the University of Chicago at a time when their curriculum was determined by their Great Books program, from which Gardner seems to have profited greatly. He graduated in 1936, worked for a few newspapers, then spent four years as a yeoman in the US Navy during the Second World War. After the war, he moved to New York and took up a writing career, working principally for Humpty Dumpty's Magazine, founded in 1952, for which he contributed articles on such things as paper-folding for kids. He also began a lifelong campaign against pseudoscience with a book in 1952 that morphed into Fads and Fallacies in the Name of Science (1957).

We could talk about many aspects of his career (his annotated editions of Alice in Wonderland come to mind), but today we are going to showcase his "Mathematical Games" column for Scientific American, which began in January of 1957 and ran for 25 years under his authorship. I read that first column when it came out. In fact, I read the article that inspired the idea for the column, a piece on "Flexigons" that Gardner contributed to the December 1956 issue. I was only in ninth grade and had never encountered a mathematical game before, except for magic squares. I was soon sitting at the kitchen table, cutting, numbering, folding, and taping strips of paper to make “hexaflexagons” to amuse myself and family.

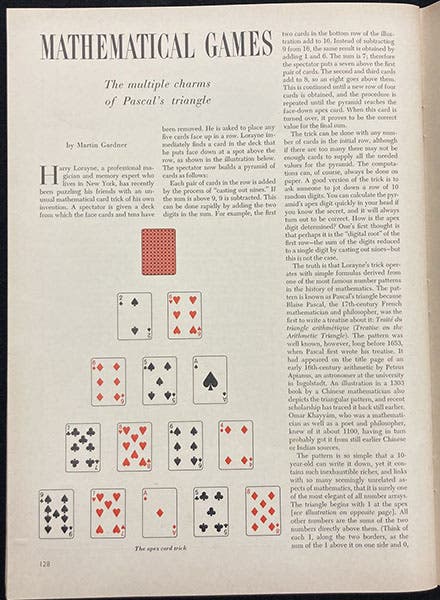

The first real column of January 1957 (third image) was on magic squares, which probably caught my interest, since I knew something about them. Next month Gardner offered a batch of problems and puzzles, on South Seas islanders who always lie, or always tell the truth, or on boxes containing either white or black marbles, or how to pick out a counterfeit coin from 10 stacks with a scale in the least number of steps. I was enthralled and stayed enthralled for the next 25 years, as apparently did millions of other readers. It has been said by many that Gardner did more to advance interest in mathematics among young people than any other person in the United States. It is certainly true in my case.

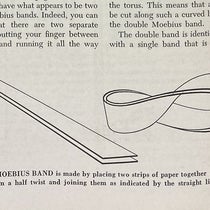

The irony is that Gardner was not a mathematician. He got through calculus, but that was it. Many mathematical educators sneered at math puzzles and games as having nothing to do with real mathematics, and Gardner tried his entire life to get math teachers to use logic puzzles and games to whet the interest of students, without much success from the people who design curricula, although many individual teachers saw the wisdom of Gardner's suggestion, and started math clubs to introduce students to Moebius strips, the tower of Hanoi, the 7 Bridges of Königsberg, and new games like Hex and Life, which Gardner introduced to the world through his column, as soon as they were invented.

“The multiple charms of Pascal’s triangle,” Mathematical Games column by Martin Gardner for Scientific American, December 1966, p. 128 (author’s collection)

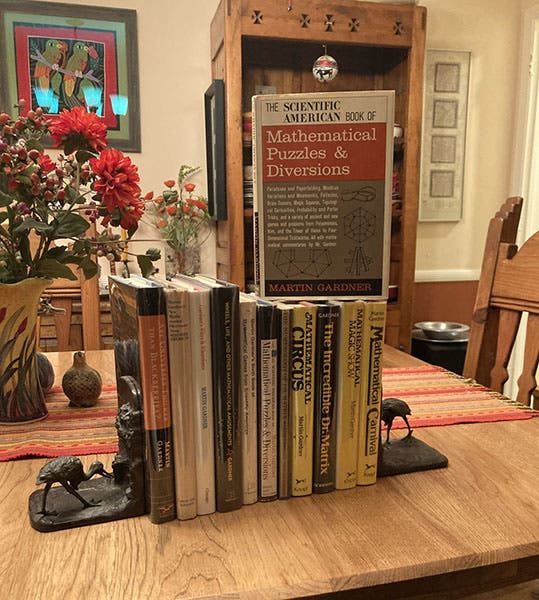

I still have all those Scientific Americans, except for the first year, when I did not yet have my own subscription. But I don't consult them much, because in 1959, Gardner started publishing book collections of his columns. I don't know how many of these he compiled, but I have 12 in my library, beginning with the first, The Scientific American Book of Mathematical Puzzles and Diversions (last image). Any one of these will delight you for hours on end, and you do not need any mathematical skills at all, although you must be curious, and capable of being amazed. And I suppose a logical mind will help.

Author’s collection of books on mathematical games by Martin Gardner, with his first collection (1959) standing on top (photo by the author)

As I was writing this piece, I noticed an issue of Scientific American from 1966 peeking out of the stack on my desk. I had used it in writing a post on Geoffrey Burbidge not long ago. Out of curiosity, I looked to see the subject of the Mathematical Games column. It was Pascal’s triangle and its use in magic tricks (fifth image). Thirty minutes later, I reluctantly put the magazine down and returned to my compositional task. I was more than intrigued to find that Gardner’s column could still have that kind of effect on me.

Gardner was probably just as influential in his campaign against pseudoscience and spoon-benders, where he attracted the support of such colleagues as Carl Sagan, but that must be a story for another day. Gardner wrote and puzzled until the day he died, age 95, on May 22, 2010. Rarely has a man who was not a mathematician received such an outpouring of laudatory obituaries and memorials from those who were, and who appreciated how Gardner had shaped their lives and futures when they were young.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.