Scientist of the Day - Martin Klaproth

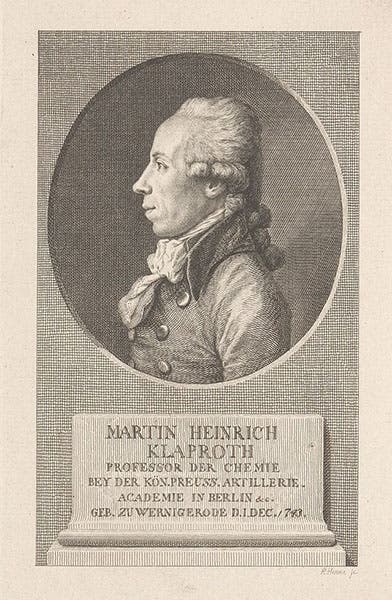

Martin Heinrich Klaproth, a German apothecary and chemist, was born on Dec. 1, 1743, in Wernigerode, a small town in central Germany. His father was a tailor; Klaproth chose to become an apothecary, and pursued that profession, as one did in those days, by a series of apprenticeships, in places like Quedlinburg, Hannover, and Berlin. He finally settled down in Berlin, where he became manager of a prominent apothecary business. He eventually established his own shop in Berlin.

We tend to equate “apothecary” with “pharmacist,” but in 18th-century Germany, an apothecary was much more a chemist than a dispenser of pharmaceuticals. This was certainly the case with Klaproth, who turned his apothecary business into a chemical research laboratory, one of the largest private chemical laboratories in the world. Someone coined the term "artisanal chemist" to describe Klaproth, a term spun off from "artisanal mining" to describe someone working independently, and it seems appropriate, although a quick search of Wikipedia reveals that Klaproth is the only person so described. He has probably been singled out because this lone independent pharmaceutical chemist discovered two elements, co-discovered four more, and confirmed the existence of two others, quite an achievement for a lone artisan.

One of those elements, the first one he discovered, in 1789, is as famous as an element can get – it was uranium, which Klaproth identified in an ore from the Harz mountains called pitchblende, which had been used since Roman times as a source for a yellow dye, but whose elemental makeup was not worked out until Klaproth did so. He did not isolate the pure metal, but he did isolate uranium oxide. Klaproth also named the new metal, after the Greek deity Uranus. William Herschel had discovered a new planet in 1781, but he called it Georgium sidus, George's star. Only Johann Bode in Berlin was an advocate for the name Uranus. Perhaps Klaproth was providing some support for Bode when he named his new element after the Geek god.

That same year, 1789, Klaproth discovered zirconium, and over the next 14 years, he co-discovered or played some role in the discovery of strontium, titanium, chromium, cerium, tellurium, and beryllium. This is an amazing list of accomplishments for an artisanal chemist.

The year 1789 also saw the publication of Antoine Lavoisier's Elements of Chemistry, in which, among other things, he introduced the modern meaning of “element,” and provided a list of such elements, including recent discoveries like oxygen, nitrogen, and hydrogen (to use their modern names). Klaproth supported the innovations of Lavoisier and did his best to improve the list of known elements. Only Humphry Davy would do better, but he had the advantage of the discovery of electrolysis as a new tool for analytic chemists.

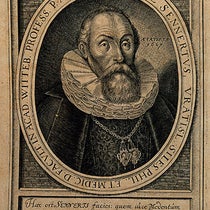

Klaproth was recognized in his own lifetime as an eminent chemist; he became director of the Berlin Academy of Sciences, and when the University of Berlin was established in 1809, Klaproth was invited to become the first professor of chemistry. The mystery is what happened to Klaproth's reputation after his death in 1817. Unlike Lavoisier and Davy (and Berzelius in Sweden), Klaproth is hardly known today, for no reason anyone can point to. It would probably help if there were a dramatic story attached to some aspect of his life, or one of his discoveries. If there is, I have not run across it.

It would also help if our library owned a book by Klaproth. But he wrote very few – most of his publications were articles in journals – and we do not have a single book by Klaproth. We have a book by his son, Julius, an eminent linguist and orientalist, who may be more famous than his father. That is definitely not fair.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![Agama colonorum (Spiny agama), hand-colored lithograph, cropped, Neue Wirbelthiere zu der Fauna von Abyssinien, by Eduard Rüppell, [v. 3] Amphibien, plate 4, 1835 (Linda Hall Library)](https://preview-assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/42f3e8a2-b691-4d33-abd7-55d0d07fc1be/Ruppel%201.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)