Scientist of the Day - Michael Sendivogius

Michael Sendivogius, a Polish alchemist and physician, was born on Feb. 2, 1566, in Łukowica. He was educated at Kraków, and spent his career at a number of German and Polish universities, before moving to Bohemia and the court of Emperor Rudolf II at Prague, about the time that Tycho Brahe and then Johannes Kepler were there. Here Sendivogius published his best known and influential book, Novum Lumen Chymicum, (New Light of Alchemy, 1604).

Before we look at a translation of this work, let me mention that if you look up Sendivogius in most encyclopedias, the article will probably begin by stating that Sendivogius almost discovered (or did discover) oxygen, 170 years before it was officially discovered by Priestley and Scheele in the 1770s. Sendivogius supposedly did this by heating saltpeter and noting that an air was given off that supported combustion. This may be true – it is certainly an oft-told tale – but no one cites a primary source, and I find no mention of a salubrious air in the one book of his available to me., which we will now introduce.

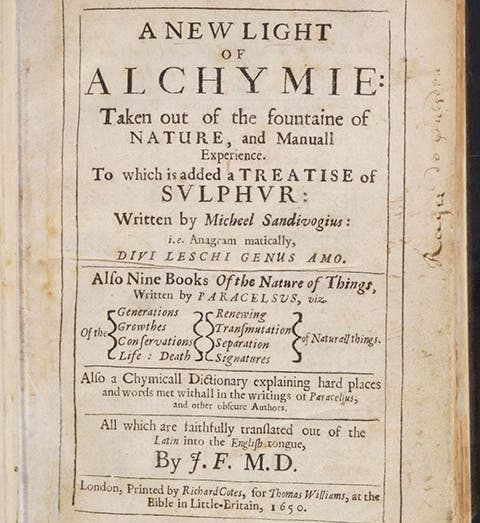

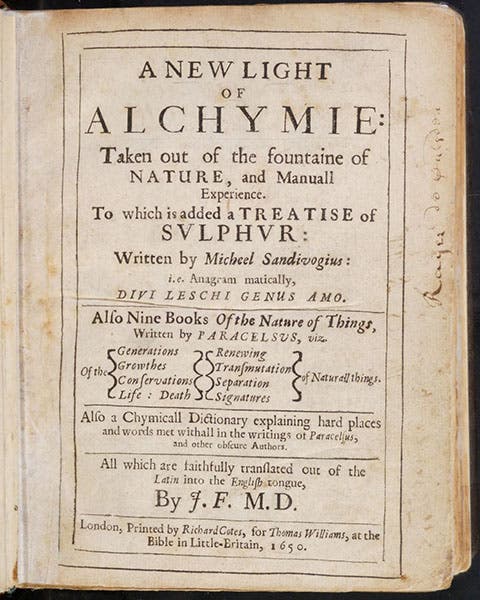

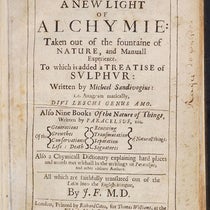

Sendivogius's A New Light of Alchymie was published in London in 1650. It was translated by John French, a London apothecary. French also included in the same volume a translation of Nine Books of the Nature of Things, by Paracelsus. The fact that he put Sendivogius first, and Paracelsus second, is more than a little interesting, considering that we now tend to consider Paracelsus as the dominant alchemical figure of that era.

A New Light of Alchymie is about the Four Elements of classical matter theory, and the Three Principles (Mercury, Sulfur, Salt) of Paracelsian alchemy, and the quest to find the Philosopher's stone, which can assist in transmutation. Sendivogius also discoursed at length about "seeds," not only animal and vegetable, but mineral, since he was convinced that metals must generate somehow, or we would long ago have run out of them. He thought that the primary mineral seed must be a form of nitre, and this "central nitre" theory must have given rise to the story about Sendivogius discovering oxygen.

The thing that surprises me about Sendivogius is how many mid-17th-century alchemists and chemists were influenced by him. In the old days, we were taught that chemists like Robert Boyle and Isaac Newton rejected alchemists like Sendivogius and their search for alkahests, elixirs, and "the stone". The modern generation of Boyle and Newton scholars are demonstrating that this is not true – esoteric alchemy was very much alive in the early days of the Royal Society, and the nature of the philosopher's stone was as hotly debated in 1660 as it was in 1600.

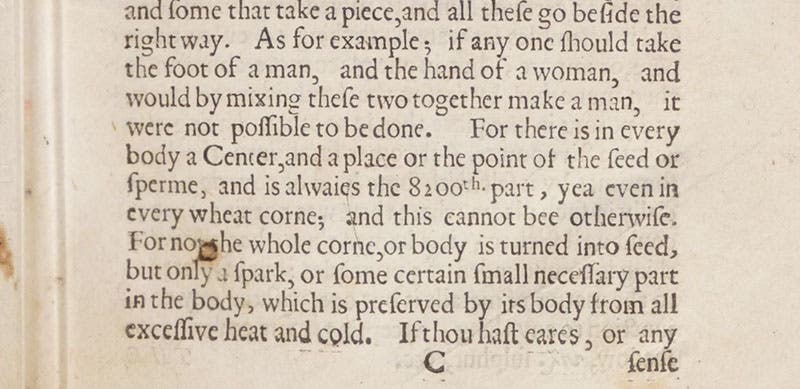

In chapter 3 of A New Light of Alchymie, Sendivogius was discussing seeds, and he said that the truly vital part of the seed, the "spark," is incredibly tiny, only 1/8200 the size of the visible seed (fifth image). This is such an odd and precise number, that it can be used as a measure of whether someone has been reading Sendivogius. I have seen the number in Athanasius Kircher, and I have heard that it turns up in other writings in the 1660s. I hope that someday, someone more versed in alchemical literature than I am, does a census of what we might call the Sendivogian number.

I do not know much about John French, or why he thought in 1650 that the English-speaking world needed translations of both Sendivogius and Paracelsus. I do know that French wrote a book of his own, The Art of Distillation (1651), and that we have this book in our collections. Perhaps French should be a Scientist of the Day himself.

There is no really good contemporary portrait or engraving of Sendivogius, so I thought I would show one of the many historical paintings that were popular in Poland in the 19th century (second image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.