Scientist of the Day - Percival Lowell

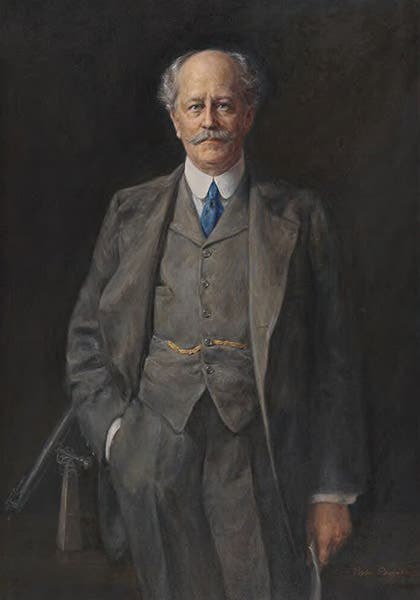

Percival Lowell, an American businessman, astronomer, and observatory director, died Nov. 12, 1916, at the age of 61. Lowell came from a moneyed and distinguished Boston family, and he spent quite a few years in the Far East, establishing business connections, and he wrote and published several books on Korea and Japan, none of which we have in our collections. After his return in the early 1890s, he almost instantly turned himself into an astronomer. He says he read Camille Flammarion’s book on Mars, and then learned about Giovanni Schiaparelli’s claim to have seen canali on Mars (canali means channels, not canals), and Lowell was hooked. Mars would be the focus of his life for the next 15 years.

Discovering very quickly that Mars defies easy observation – it is so small in a telescope that it is difficult to make out any details – Lowell determined to build an observatory designed specifically for observing Mars. Since even the slightest disturbance in the air will blur the features of Mars, he decided to build an observatory on as elevated a site as he could find, so that the telescope was above much of the atmosphere, and in a remote region, where there was little atmospheric pollution. He chose Flagstaff, Arizona as a suitable site, and the Lowell Observatory was erected there at an altitude of 7200 feet; it was up and running by 1894. Lowell ordered a 24-inch refractor from the Alvan Clark sons in Cambridge; until it was ready, he used a smaller refractor built by John Brashear.

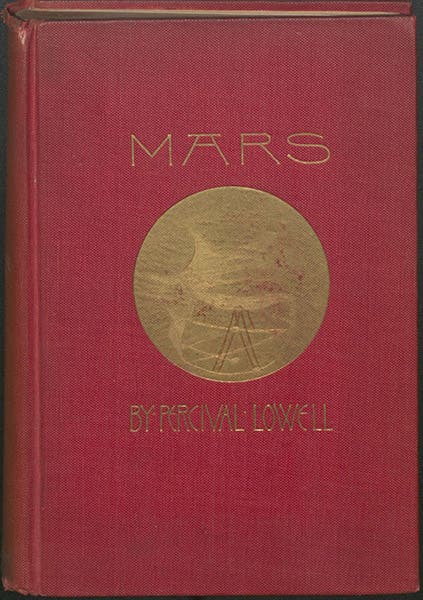

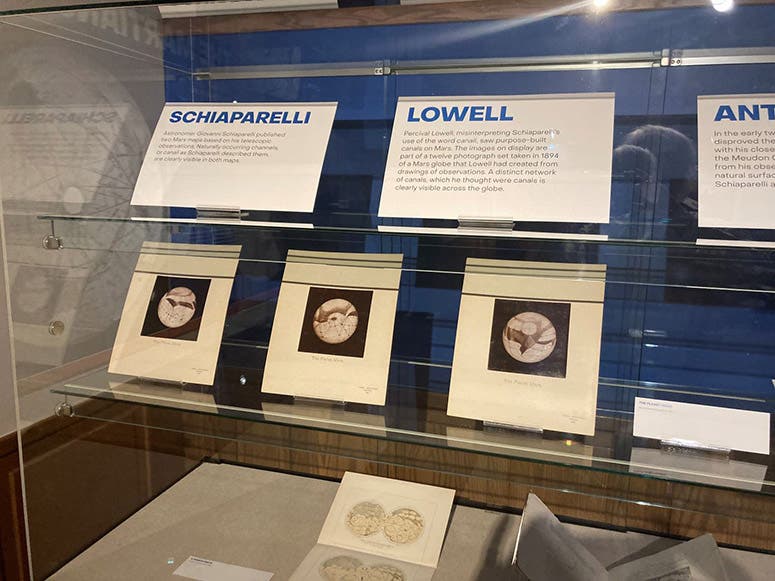

Nine years ago, I wrote a post on Lowell, in which I focused on the first publication to come out of the Lowell Observatory, a set of 12 photographs of a Martian globe, mounted on thick card stock, that showed the Martian canals as Lowell perceived them. It is dated 1894, the same year the Lowell Observatory was founded. This is by far the showiest item concerning Mars that Lowell ever published, but we should not have begun with it, because only a few copies were distributed, and it had no effect on the public. Today, we will consider the book that did make a difference, a work simply called Mars, that was published back in Boston in 1895 and generated considerable public and professional reaction.

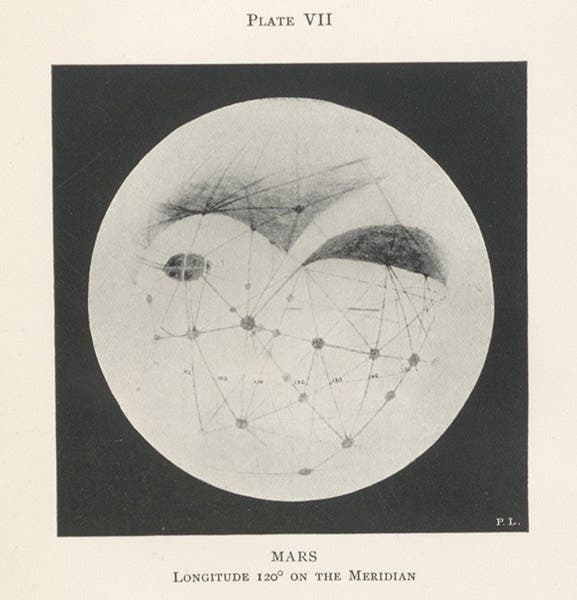

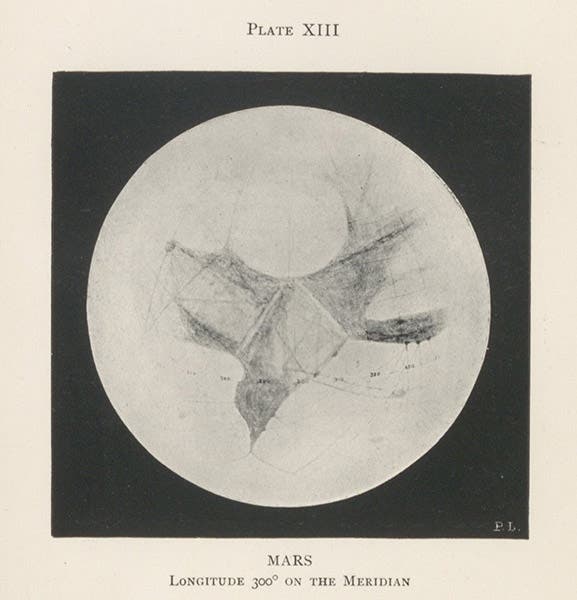

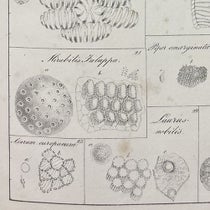

The book has a showy cover (third image), embossed with a view of Mars, and 12 plates of Mars from various viewpoints, black-and-white half-tone counterparts to the larger sepia-toned photographs in the box of 12 photos that we discussed and illustrated in our first post. We show here a view that includes Solis Lacus, the eye-like formation that is one of Mars' most recognizable features (fourth image), and the other distinctive feature, Syrtis Major, which looks like the Indian subcontinent (fifth image).

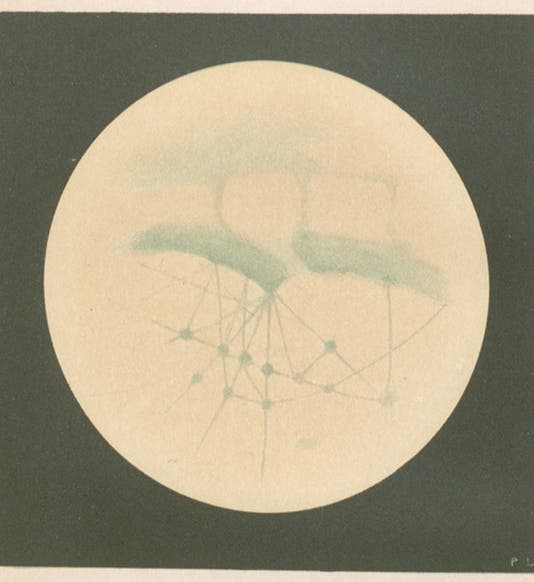

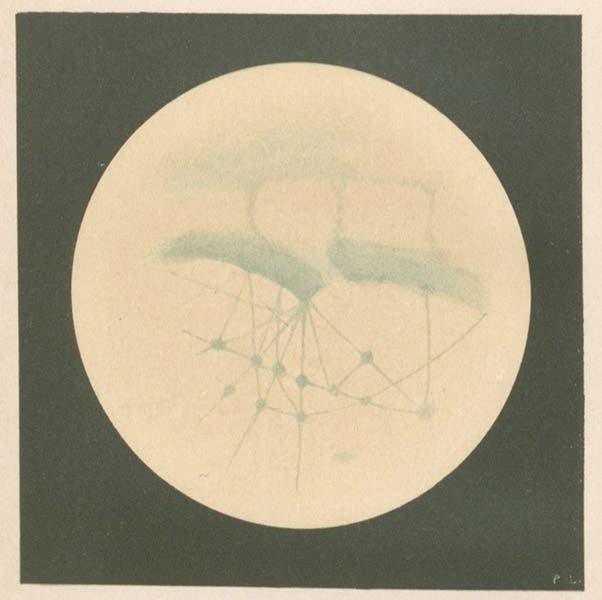

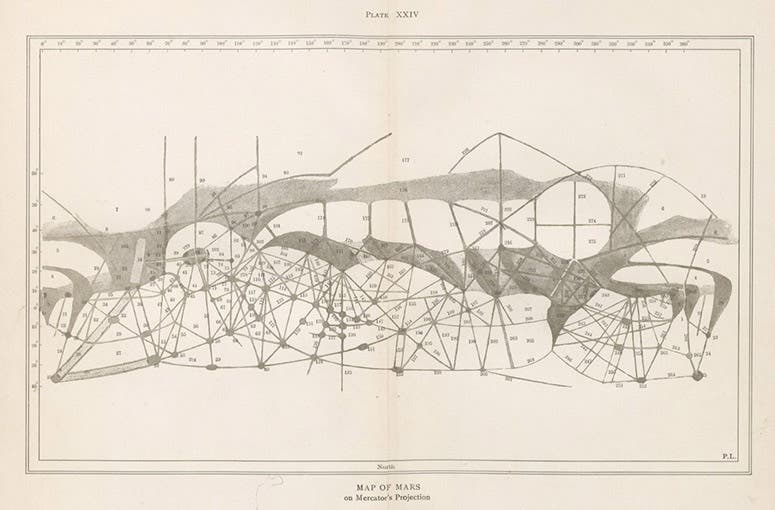

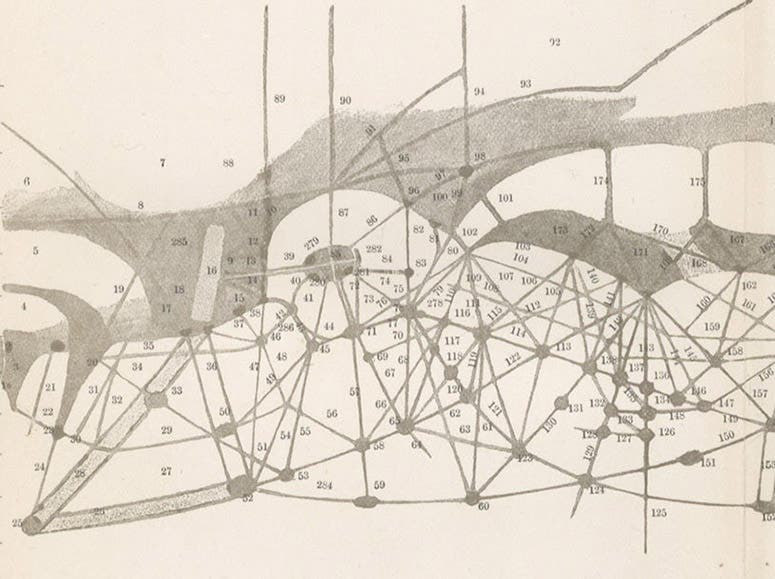

There is also a splendid frontispiece, the only color plate in the book, that shows the Sinus Titanum feature (first image). At the end of the book, there is a folding map, on the Mercator projection, of the entire surface of Mars. Percival Lowell himself drew this, as he drew all the other views in the book. We show the complete map (sixth image), and a detail of the Solis Lacus region, where you can sate your appetite for Martian canals (seventh image).

No one knows what Lowell and his adherents were seeing when they saw canals on Mars. Mars lies right at the limit of resolution of the human eye, and the eye is very good at connecting dots with lines when given the chance, and Mars has lots of dots, in the form of extinct volcanoes. Some people saw canals, and some did not, and they could do little but argue until planetary photography got better, and even then, there was room for doubt. Not until Mariner 4 whizzed by Mars in 1965 would we have real evidence that the canals are simply not there.

Lowell thought the canals were built by a dying Martian civilization to bring water from the polar caps to slake the thirst of an increasingly parched and dying world. We will discuss this more when we write a post on the second and third of Lowell’s books on Mars, published in 1906 and 1908, in the last of which he responds to a critic, the evolutionist Alfred Russell Wallace. We have all these works in our collections.

One case in the exhibition, Life Beyond Earth, at the Linda Hall Library, showing three of Percival Lowell’s photographs of his Martian globe (photo by the author)

Not long ago, we opened a new exhibition at the Library, Life Beyond Earth?, which looks at the search for extraterrestrial intelligence and its precursors, which would certainly include Lowell and his claim to have detected canals on Mars. Three of the 1894 photographs of his Martian globe are on display in the exhibition (eighth image). You may learn more about the exhibition here.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.