Scientist of the Day - Pope Julius II

Pope Julius II, known as Giuliano della Rovere until ascending to the papacy, was born Dec. 5, 1443, in a town in the Republic of Genoa. The della Rovere house was a noble one but not especially wealthy; fortunately, Giuliano's uncle was elected Pope Sixtus IV in 1471, and, in a blatant act of nepotism, the 28-year-old Giuliano was appointed bishop, and a month later, cardinal, and given benefices that resolved his financial problems.

Giuliano was incensed at the election in 1492 of Pope Alexander VI, the Borgia Pope, who tried, unsuccessfully, to have Giuliano assassinated several times, while Giuliano stayed out of Rome. Giuliano was involved in the Italian Wars that began in 1494, and many times led troops into battle. But we are going to pass over this part of his career and get right to his election to the papacy, which occurred in 1503. He took the name Julius II, not because he admired Pope Julius I, it is said, but in admiration of Julius Caesar, conqueror of Gaul. Julius established himself as a warrior pope, but he also launched a campaign to beautify Rome and reestablish the arts. He decided to rebuild the now-decrepit basilica of St. Peter’s and hired Donato Bramante to do the job. He commissioned Michelangelo to decorate the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

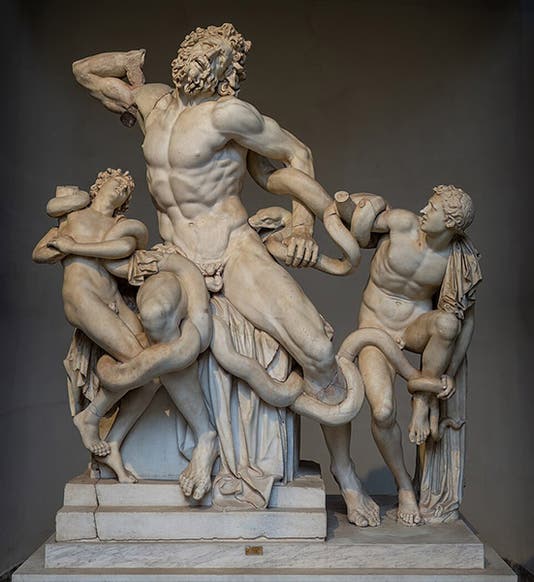

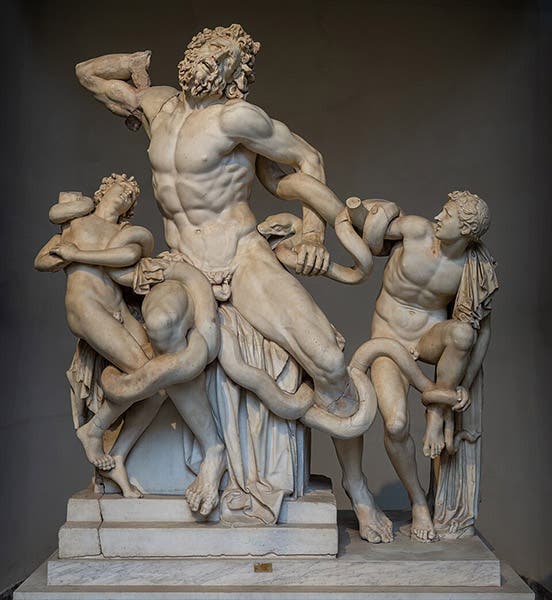

But the most novel contribution of Julius II to the arts in Rome was to commission Bramante to design a courtyard to connect St. Peter’s with the Villa Belvedere, a papal summer house, and then to contribute his own collection of antique statuary to decorate the Cortile del Belvedere. It was an extraordinarily gathering of sculpture, and it grew more extraordinary during the 10 years of his papacy, as he quickly snatched up new finds as they were unearthed. The Belvedere collection included some of the most famous examples of Greek and Roman sculpture, including the Apollo Belvedere (third image), Sleeping Ariadne (fourth image), the Venus Felix, the River God Tiber, Hercules and Antaeus, and, after it was unearthed in 1506, the marvelous Laöcoon (first image) that so enthralled Michelangelo. Most of these continue to be papal property and are on display in the Vatican Museums. Only the Tiber escaped, abducted to Paris by Napoleon, and for some reason it never came home, unlike most of Napoleon’s other thefts of artworks, which were returned after 1815.

But none of this really has much to do with science. Julius makes it into this series because, in 1509, Julius asked Raphael Sanzio, then only 26 years old, to decorate the papal apartments in the Vatican, and Raphael created a number of fresco masterpieces, such as The Expulsion of Heliodorus from the Temple, or the Meeting of Pope Leo and Attila the Hun. But in the Stanza della Signatura, the room where the Pope signed and sealed his proclamations, Raphael gave Julius, and western civilization, his exquisite homage to the philosophers and mathematicians of ancient Greece: The School of Athens (fifth image). Here we can see, in one frame, Plato, Aristotle, Pythagoras, Parmenides, Heraclitus, Socrates, Euclid, and Ptolemy, interacting in a wildly impossible yet totally plausible way. It is possibly the greatest gift the Renaissance would offer to future historians of ancient science.

Raphael did not label the figures in his painting or comment on them elsewhere, but we have managed to figure out most of them, except for Archimedes, who has to be there, but we don't know where. We show below a detail of Plato and Aristotle (sixth image; Plato is on the left); you can see other details at our post on Raphael, which is devoted exclusively to the School of Athens. One of Raphael’s welcome customs was to use his friends for models, so the portrait of Plato is really a portrait of Leonardo da Vinci, while Heraclitus, leaning on his elbow at the center, is represented by Michelangelo, and Euclid, with dividers and slate at the right, sports the bald head of Bramante.

The Pope no longer lives in these apartments, so unlike Julius II, he cannot gaze at the legacy of ancient Greece while signing his decrees (or tweeting his followers), which is just as well, for he would surely be trampled to death by the thousands of tourists that flock to these rooms every day. Julius may not have contributed anything to the iconography of the School of Athens, but we would not have that painting without his patronage. Desiderius Erasmus later wrote a scathing attack on Julius called Julius Excluded from Heaven (1514), in which he attacked the entire premise of a warrior pope. But one could argue that the Cortile del Belvedere and the School of Athens might have been enough to crack open the Pearly Gates for Julius.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.