Scientist of the Day - René Descartes

René Descartes, a French/Dutch natural philosopher, died Feb. 11, 1650, just six weeks shy of his 54th birthday. We have celebrated his birthday (Mar. 31) twice, once with a discussion of his vortex theory of planetary motion, and, just last spring, with his account of the origin of the Earth. Today we are going to look at his life, because it was a life lived oddly.

Descartes was born into a privileged family, his father a lawyer and member of the Parlement at Rennes in Brittany. But he was a second son. He went to the Royal University at La Flèche, run by the Jesuits, where he got a thorough Aristotelian education, and then we think studied law at Poitiers for several years, as his father wished. He would later exhibit considerable skill in math, so he must have learned something from the algebra and geometry textbooks of the Jesuit Christoph Clavius, in use at La Flèche.

In 1618, Descartes decided to become an unpaid army officer. He chose to join a regiment of Dutch mercenaries led by Prince Maurits of Nassau, based in Breda. That this was a Ptotestant army does not seem to have bothered the good Catholic Descartes. In Dordrecht, he met Isaac Beeckman, 8 years older, who exposed Descartes to atomism, and the work of Galileo in Italy, and who recognized and encouraged Descartes’ considerable problem-solving abilities in math. There are claims that Descartes was present at the Battle of White Mountain, when Protestant and Catholic Germans clashed to begin the bloody Thirty Years War, but there is no evidence Descartes was ever actually in a battle.

A notable event, according to Descartes’ later recollection, occurred on Nov. 10-11, 1619, somewhere near Ulm, when Descartes, bedded down in a "stove-heated room," had a series of three dreams, which told him he must doubt everything he had learned in school and start over, rebuilding philosophy from the ground up using certain principles that the mind cannot doubt. These dreams have been described in great detail in many biographies, but the details did not come from Descartes, but from a later biographer, Adrien Baillet, who seems to have spun most of his account out of the blue. But Descartes later was convinced that the dreams were instrumental in determining the direction of his new philosophy.

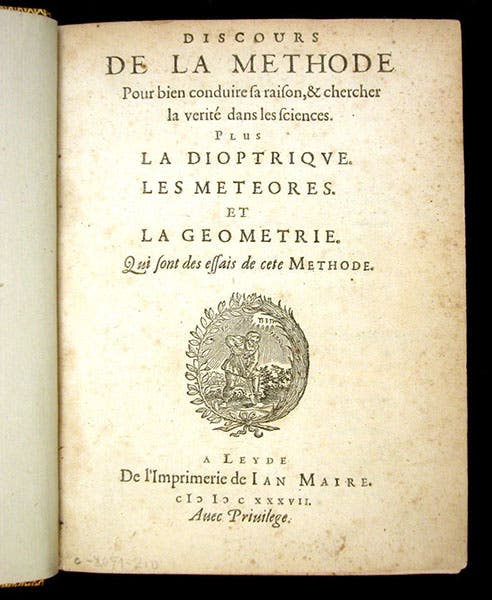

Descartes spent the years from 1619 to 1628 trying to figure out what to do, cashing in some properties inherited from his mother, and getting to know several church officials in Paris, such as Cardinal Richelieu and Cardinal Bérulle, impressing them with his talk of a new philosophy, but without writing anything. Then, shortly after the end of the Siege of La Rochelle in 1628, when tens of thousands of French Huguenot Protestants were killed (and where Descartes was present when the city fell), he abruptly left for the Netherlands, and did not return to France for 18 years. He lived in many different cities and towns, his residences kept secret from all but Marin Mersenne in Paris, who coordinated his correspondence. In Holland, Descartes wrote his unpublished World, put on the shelf when Galileo was condemned (1633); the three essays on geometry, optics, and meteorology, prefaced by his famous Discourse on Method (1637; second image); his equally famous Meditations (1641), and his Principles of Philosophy (1644), which contained his vortex theory of planetary motion and his theory of the Earth, discussed in our first two posts. None of these were published in France. In 1645, he fathered an illegitimate daughter, Francine, whose mother was a servant named Helena, and Francine’s death from scarlet fever in 1640 was, he said, the saddest day of his life.

Why did Descartes flee France and spend most of his creative life in Holland? We don't really know. He may have feared Richelieu, who was certainly someone to watch out for. He may have decided that getting involved in a purge of Huguenots in France was not the future he was looking for. He may have become too involved with libertines in France, which could make life dangerous. Some think he might even have been a spy. But the fact is, he fled all of his friends and acquaintances of the 1620s, and his family, and he did not want anyone to know where he was. He took as his motto, Bene qui latuit, bene vixit – “a life well hidden is well lived.”

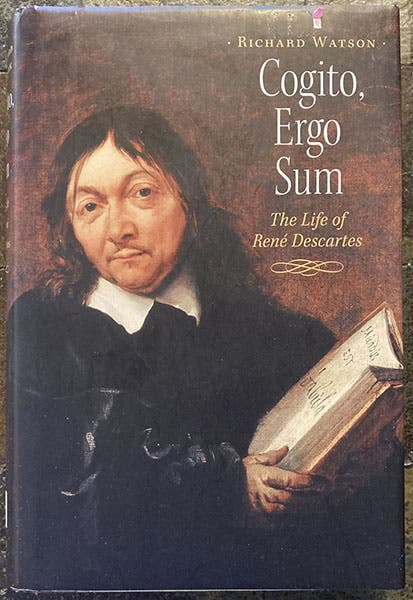

Portrait of René Descartes, Jan Baptist Weenix, painted around 1647, Central Museum, Utrecht, on the dust jacket of Cogito, Ergo Sum: The Life of René Descartes, by Richard Watson, 2002 (author’s copy)

When his writings eventually provoked controversy among Protestant academics in the Netherlands, Descartes toyed with returning to Paris in 1647, and he thought he had secured a substantial pension, but it was never paid. He returned to Holland, and in the fall of 1649, he accepted an invitation from the young Queen Christina of Sweden to come to Stockholm to be her court philosopher. Descartes was flattered into acceptance, and arrived in the land of "bears and ice," as he called it, in December of 1649. Two months later, he was dead of pneumonia, probably not caused by his being required to tutor the Queen at 5:00 am, but that cannot have helped.

Despite all the unexplained factors of Descartes’ life in Holland, it did provide him time to reflect and write, and to experiment as well, an aspect of Descartes’ natural philosophy we shall have to return to, especially his work in anatomy.

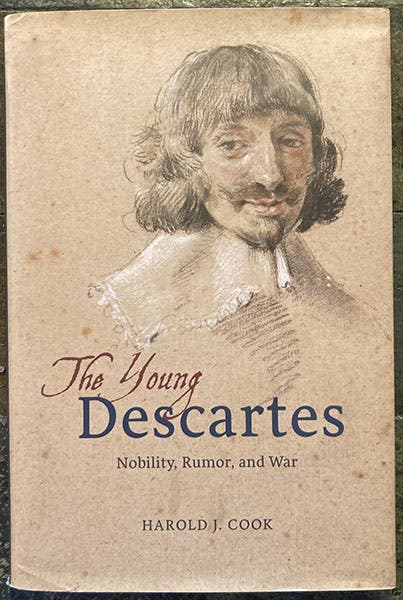

Portrait of René Descartes, by Simon Vouet, ca 1628, the Louvre, on the dust jacket of The Young Descartes: Nobility, Rumor, and War, by Harold Cook, 2018 (author’s copy)

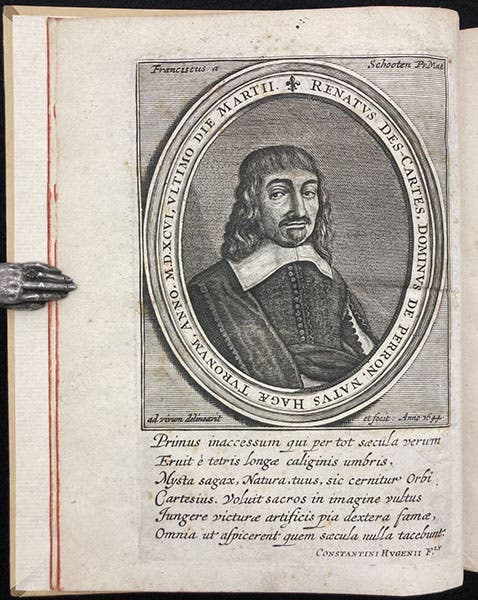

The portrait of Descartes most often used in his bios was supposedly painted by Frans Hals and is in the Louvre (first image); it was the basis for the engraving we used in our earlier post. It turns out the painting is not by Hals, although it still hangs in the Louvre. The second most reproduced is one drawn from life by Franciscus à Schooten in 1644 – we have many impressions of it, since it appeared in nearly every posthumous edition of Descartes’ Opera (third image). But there are two others that deserve to be better known. One is by Jan Baptist Weenix, painted around 1647, which is in the Central Museum, Utrecht. By happy circumstance, it adorns the dust jacket of one of my favorite biographies of Descartes, Cogito, Ergo Sum: The Life of René Descartes, by Richard Watson (2002; fourth image). The other, portraying a much younger Descartes, by Simon Vouet, ca 1628, is in the Louvre, and it just so happens to grace the cover of another and more recent biography, The Young Descartes: Nobility, Rumor, and War (2018), by Harold Cook (fifth image).

Amazingly, with all this, we have hardly scratched the surface of the importance of Descartes for the emergence of early modern science. It is a good thing there are more February 11ths, and March 31sts, to come.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.