Scientist of the Day - Robert FitzRoy

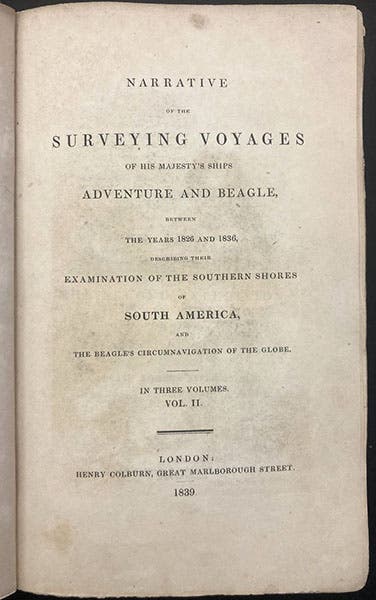

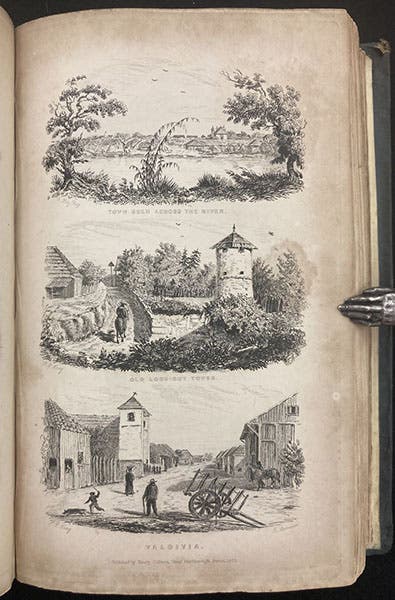

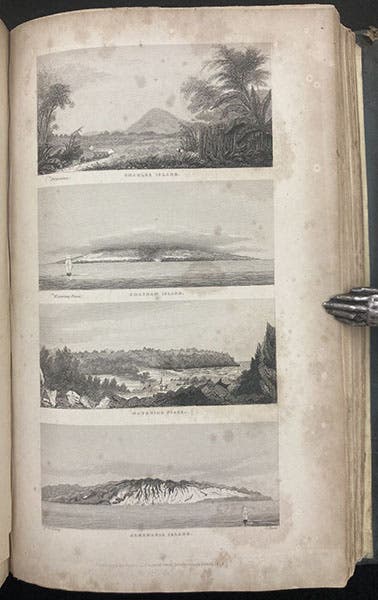

In February of 1835, Charles Darwin was in the third year of his voyage on HMS Beagle. He and Captain Robert FitzRoy and the rest of the crew had taken their time surveying and exploring Brazil, Argentina, and Tierra del Fuego (third image), and they were now on their way north on the western coast of South America, visiting the many islands and port cities of Chile. They had not yet reached Ecuador and the Galápagos Islands.

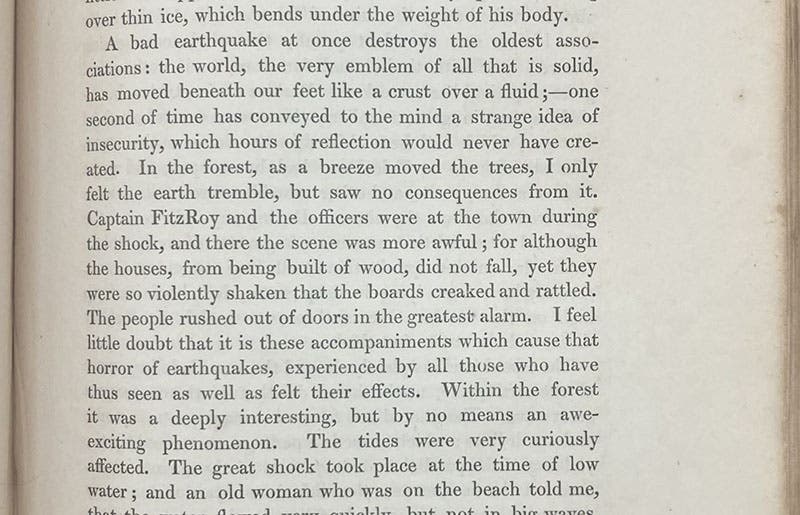

On the morning of Feb. 20, 1835, the Beagle was at anchor at Valdivia, some 280 miles south of Concepcion. FitzRoy was in town, Darwin was out on a hike, and taking a nap in the woods, when an earthquake struck. It was Darwin's first earthquake ever, and introduced him to the unnerving experience of having the solid earth turn liquid beneath him (see his description, fifth image), but out in the forest, there was not much damage. Destruction was more widespread in Valdivia, said Darwin, alhough FitzRoy did not describe it in his narrative of the voyage (second image).

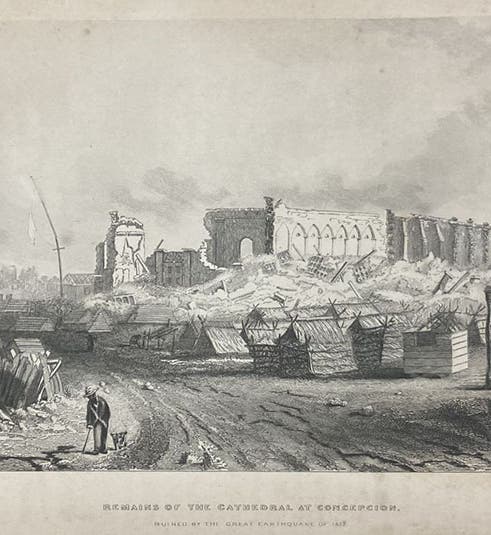

The crew packed up the Beagle and headed north to Concepcion, finally arriving on Mar. 4, where FitzRoy and Darwin suddenly came to a new understanding of what an earthquake can do. The cathedral city was right at the epicenter of the quake, and in less than 2 minutes of violent shaking, the entire city had been destroyed, including the cathedral. Darwin marveled that anyone was still alive, but the deep-seated Andean instinct of running outside at the first sign of a tremor had saved most of the population.

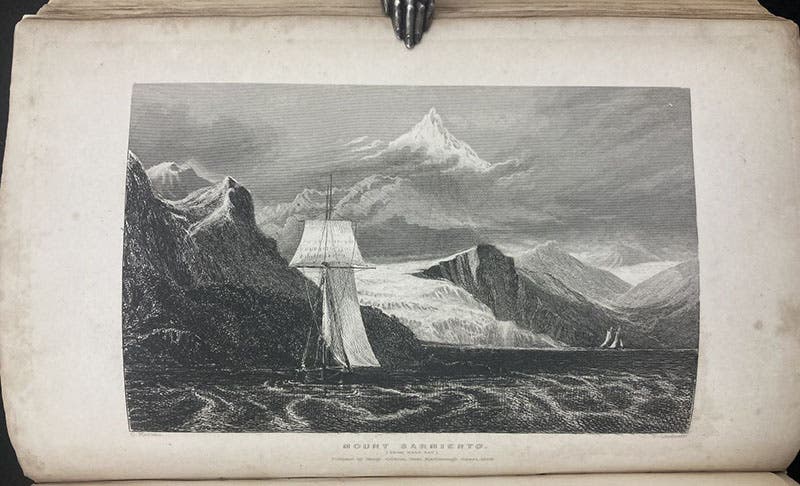

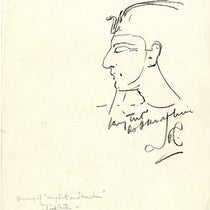

Both FitzRoy and Darwin wrote extensively about the 1835 Concepcion earthquake in the four-volume Beagle narrative, FitzRoy in volume 2, and Darwin in his own volume, volume 3, with its exciting title, Journal and Remarks (last image). As captain, FitzRoy commandeered all the illustrations, so the only image of a devastated Concepcion is found in Fitzroy's account (first image). It is sometimes attributed to Darwin, but it is clearly signed, “J.C. Wickham.” John Clements Wickham was First Lieutenant on the Beagle. He could draw a lot better than Darwin could.

The Concepcion earthquake played an important role in Darwin's geological education by making him aware of the dynamic nature of some geological forces. Everything in England was slow subsidence and erosion; here in the Andes, coastal land could be raised up 10 feet in a day, and it was easy now to imagine that the shells he would soon see in a mile-high pass near Valparaiso had been raised from the sea floor by similar disruptive forces. This was not catastrophism. But it was uniformitarianism with an oomph! And it gave Darwin new respect for the power of the Earth.

Since we had FitzRoy's volume of the four-volume narrative of the two Beagle voyages out anyway, to photograph the etching of Concepcion after the great earthquake, we thought we would show you several other plates from that volume. The plate of Mt. Sarmiento in Tierra del Fuego is often reproduced – we include it here (third image) because it depicts HMS Beagle. But the plate showing three views of Valdivia is never reproduced, attractive though it might be (fourth image). And when discussion comes to the Galapagos archipelago, which the Beagle reached on Sep. 15, 1835, everyone switches to Darwin's volume, Journal and Remarks, to see how he reacted. But he has no illustrations, and we forget that FitzRoy included four views of three Galápagos Islands in his volume, one of which he drew himself. These are never reproduced, so we include them here (sixth image). I wish FitzRoy had been interested in iguanas, tortoises, and finches, but he was not.

The 1835 Concepcion earthquake is estimated to have been magnitude 8.5 on somebody’s scale, which is sizeable. It was caused, we now know, by the downthrust of the Nazca plate beneath the South American plate. The same forces caused the 2010 Chile earthquake in nearly the same location, which was of a similar magnitude to the earthquake experienced by Darwin and FitzRoy.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.