Scientist of the Day - Samuel Alken

Samuel Alken Sr., an English artist and engraver, was born Oct. 22, 1756, in London. Alken got his art training at the school of the Royal Academy in London, and sometime after 1780, he mastered the newly invented form of etching, called aquatint.

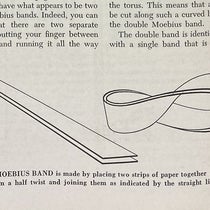

Conventional etching, which had been in use for three centuries, starts with a copper plate covered with a wax-like substance, called the "resist". The artist then uses a needle to scratch through the resist down to bare copper. When the plate is placed in an acid bath, the acid eats (etches) the bare copper lines and leaves the resist alone. The resist is then removed by a solvent, and the plate is inked, wiped, and printed. The etched lines hold ink and print; the areas once covered by resist do not. It is a wonderful process, especially in the freedom it gives to the artist.

Aquatint uses the same principle of "acid eats copper," but differs in the way the resist is applied. A very fine powdered resin is sprinkled uniformly onto a copper plate, which is then gently heated until the powder melts, spreads out, dries, and cracks, leaving a thin lacelike network of copper showing between the bits of melted resin. The length of time spent in the acid bath determines how deeply the network will etch, and thus how dark an area will print. The artist can paint resist on the plate at any point to make white or light areas, a process called “"stopping-out". He can also use an etching needle to outline areas or draw figures. Alken mastered all this and became one of the first English practitioners of aquatint.

Detail of third image, showing characteristic signs of an aquatint, especially the light areas produced by stopping-out, aquatint by Samuel Alken in Observations Relative Chiefly to the Natural History, Picturesque Scenery, and Antiquities, of the Western Counties of England, by Willam George Maton, vol. 2, p. 84, 1797.

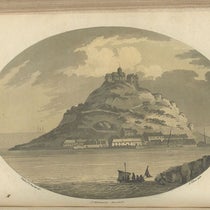

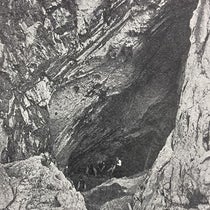

William George Maton, a would-be physician fresh out of Oxford, took a trip through the "Western Counties" of England in 1794-95, making notes on the natural history, geology, and antiquities of Cornwall, Dorset, Devon, and Somerset. He traveled with two friends, including the Reverend Thomas Rackett, who made drawings of some of the sights they encountered. Maton then compiled his notes and Rackett’s drawings into a book. By the 1790s, aquatints were being used more and more to reproduce landscapes for travel books, and either Maton or his publisher – probably the latter – found Alken, who had just illustrated a similar kind of book project, published in 1796. Maton's book was published in 1797, as Observations Relative Chiefly to the Natural History, Picturesque Scenery, and Antiquities, of the Western Counties of England, made in the years 1794 and 1796. Illustrated by a Mineralogical Map, and Sixteen Views in Aquatinta by Alken, and as the end of the title tells us, the illustrations were aquatints by Alken, 16 of them.

We display here some of Alken's handiwork, including a few details to show the texture of an aquatint, and how the "stopping-out" technique can be used to produce light areas of clouds or sunlit rock faces (fourth image). We also show details of the signatures of the artist Rackett (sixth image), and of Alken, whose name is at the bottom right of each aquatint (eighth image).

Interestingly, Maton was so pleased with the prints that he dedicated the book to Reverend Rackett and did not mention Alken anywhere, except at the end of the wordy title page, and that was likely the publisher’s doing. Maton probably did not realize that Rackett’s drawings were ordinary at best, and that the prints made such a strong impression because of the aquatint process, executed so ably by Alken.

Alken's aquatints are some of the earliest we have in our library. Techniques improved and aquatints got better in the period from 1800 to 1835, as you can see in our posts on Thomas Garnett, Charles Panckoucke, and T. G. Cumming. Aquatints were gradually replaced in the 1830s by lithographs, which are equally capable of reproducing landscapes, but which allow greater freedom to the artist, who can now draw directly on a lithographic stone with his crayon.

Maton's book also contains a folding geological map at the end that was not an aquatint but a conventional engraving. It was one of the earliest geological maps of any part of England, printed some 18 years before the more famous maps of William Smith. I will write a post on Maton's map someday.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.