Scientist of the Day - Thomas Pennant

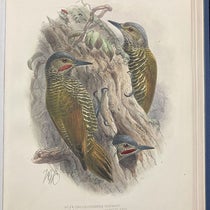

Thomas Pennant, a Welsh naturalist and traveler, died at his home, Downing Hall, in Flintshire, on Dec. 16, 1798, at age 72. Pennant began his writing career as a naturalist with a sumptuous two-volume folio, The British Zoology, adorned with 107 large hand-colored engravings of a variety of mammals and birds native to the British Isles. We have this set, and featured it in our first post on Pennant. It is one of the primary sources for the hedgehog images that we rotate through the masthead for our house journal, The Hedgehog.

Pennant began traveling soon thereafter, to Scotland, then through Wales, back to Scotland, this time including the Hebrides. He travelled on horseback, usually with his servant, Moses Griffith, who was a gifted artist, and recorded many a scene or specimen for his master. Pennant would then write up a narrative of his adventures and publish it with engravings after drawings by Griffith. We have only one of these travel narratives, about his second Scotland trip, which included the first printed images of Fingal's Cave on the isle of Staffa, some of which we showed in our second post on Pennant. In between trips, Pennant published reference works such as the Arctic Zoology, which were smaller and more affordable than The British Zoology. We showed some images in our first post, including a splendid title-page moose.

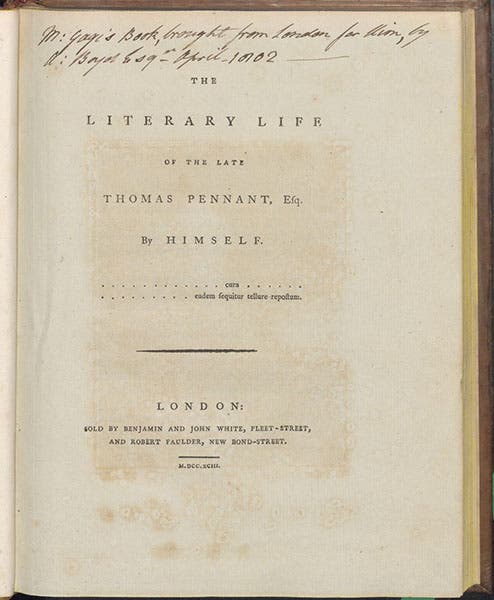

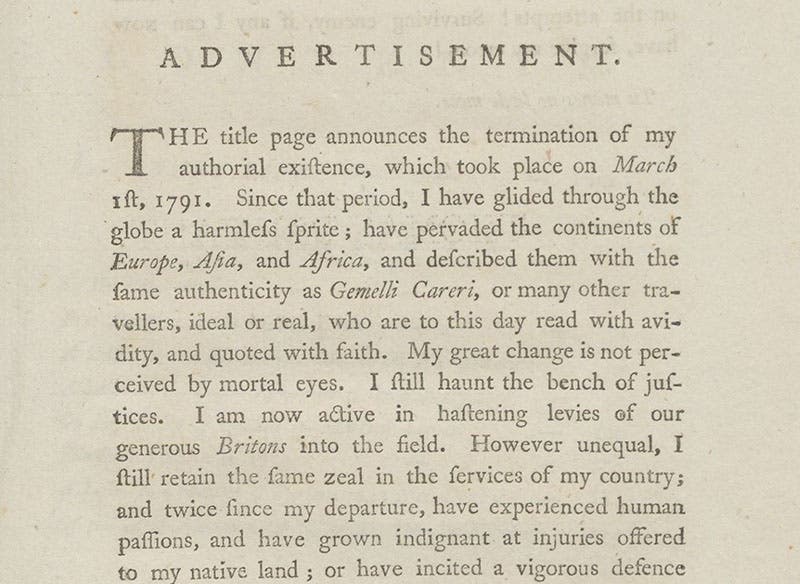

The reason that we are we are writing a third post on Pennant is that last year, we acquired Pennant's brief autobiography, The Literary Life of the late Thomas Pennant, which he published in 1793 on the occasion of his retirement, and which, not surprisingly, was no retirement at all, as he continued to travel, even making it to India, and publishing more travel narratives, six of which appeared after his death in 1798.

The Literary Life is of interest because Pennant was an inveterate correspondent, often writing to people whom he met on his travels, such as Joseph Banks in London and Peter Simon Pallas in Berlin, and some that he just liked to write to, like Gilbert White, who included over 50 letters from Pennant in his Natural History of Shelborne (1789). In his Life, Pennant is fond of singling out those who praised his work, although he did not shy away from telling us about the Comte de Buffon, whom he met in Paris, and who later took great exception to something Pennant said about one of Buffon's observations. Pennant seemed amused by and tolerant of the criticisms that often came his way. But he did like the praise better.

The feature I would appreciate in Pennant's Literary Life, if I were a Pennant scholar, is that he was very particular to give exact dates when he discussed events, or meeting someone for the first time. This is more unusual than you might think in the 18th century, when you can often have a devil of a time, in many travel narratives, just trying to figure out the year something happened. For example, after mentioning Joseph Banks, Pennant said: “our first acquaintance commenced on March 19th, 1766, when he called on me at my lodgings in St. James’s Street, and presented me with that scarce book Turner de Avibus &c., a gift I retain as a valuable proof of his esteem” (p. 9). As another example, Pennant wrote: “The Arctic Zoology gave occasion to my being honored, in the year 1791, on April 15th, by being elected member of the American philosophical Society at Philadelphia (in the presidentship of David Rittenhouse esq.)”(p. 29).

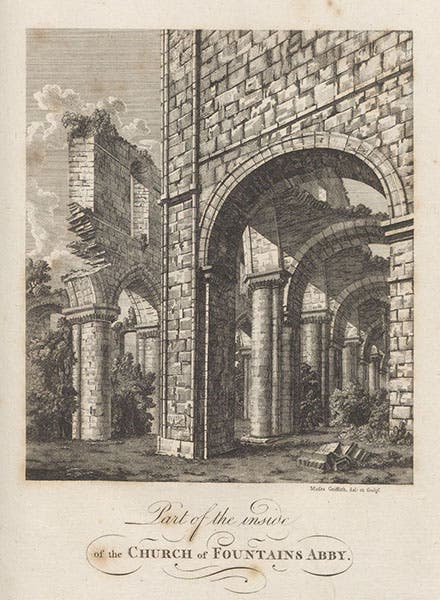

I always describe Pennant as a naturalist, but in fact he was just as much an antiquarian, and the bulk of his tours were devoted to visiting old family houses, and the ruins left in the wake of the dissolution of the monasteries under Henry VIII. It is not an accident that the only plate in The Literary Life, other than the portrait frontispiece, is an etching of Fountains Abbey, a Cistercian Monastery in North Yorkshire, drawn and engraved by Griffith (fourth image).

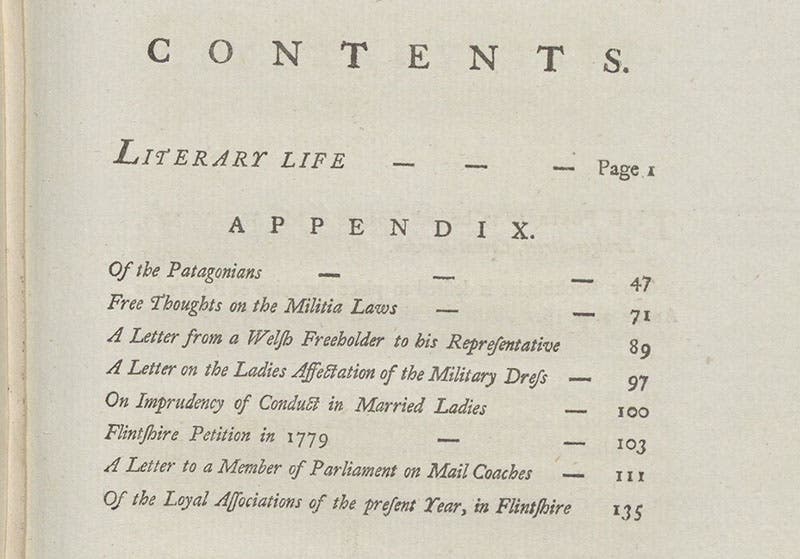

Pennant’s autobiography, as printed here, is only 45 pages long. As we can see by the Table of Contents (sixth image), the other 99 pages were devoted to political topics, in which Pennant was apparently seriously engaged, as he ranted in fury about the fact that the Crown had exempted mail-coaches from paying tolls on the roads in Wales, leaving it to the poor towns to pay for upkeep, and fining them when they could not afford to do so.

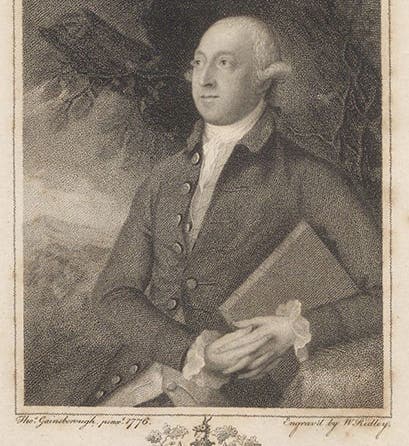

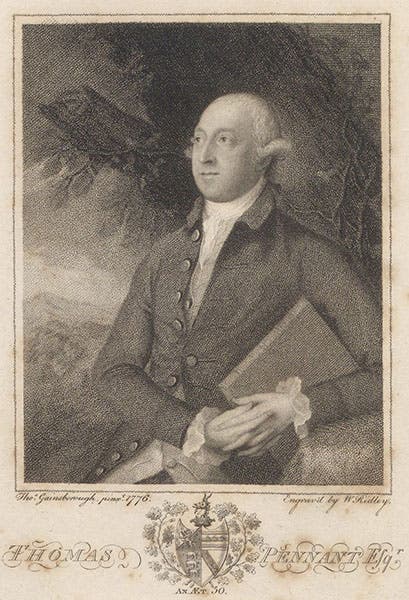

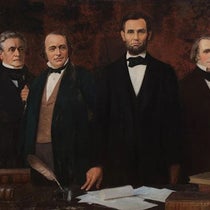

Finally, we comment on the portrait, an engraving after a painting by Thomas Gainsborough (first image). We showed the engraving in our first post on Pennant, a copy in the Wellcome Collections, because we did not then own it. But now we do, since it foms the frontispiece to Pennant's Literary Life.

Pennant was buried in the Chuchyard at Whitford, Flintshire, Wales, and has a small monument and plaque inside, near the altar, says findagave.com.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.